Hi friends, tomorrow (Thursday, September 21) at 5 p.m. Mountain, I host the monthly Zoom chat for paid subscribers. This is a fun, casual conversation during which we talk about various things related to running and wellness, and we also share personal accomplishments and challenges. If you’d like to join, please upgrade your subscription to the supporter level. You can earn a paid subscription by referring friends to this newsletter, if three or more subscribe.

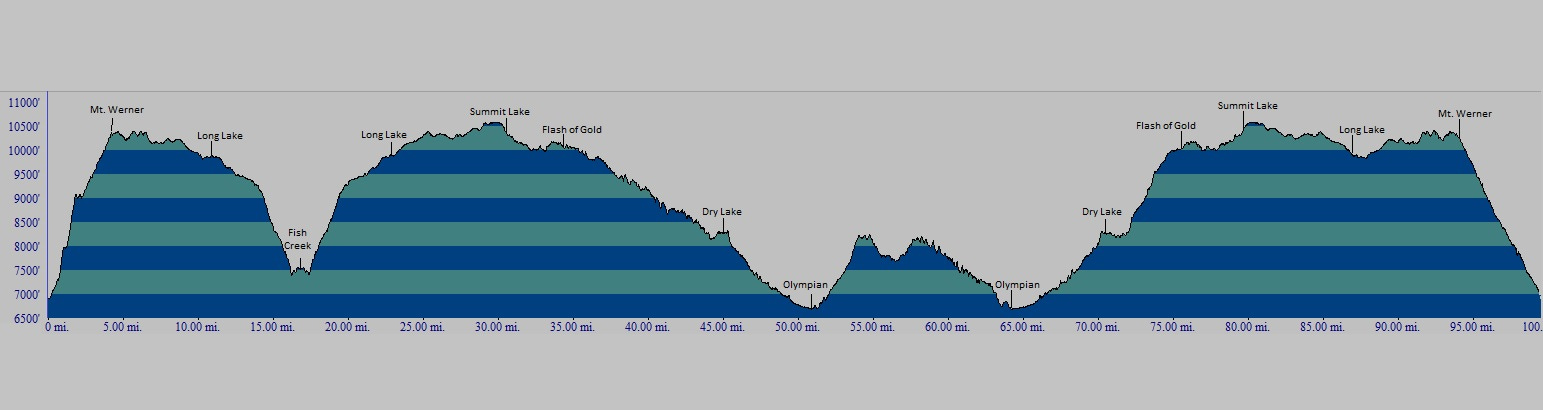

I need to remember in detail how the final stretch of last weekend’s 102-mile race felt miserable and discouraging, before memory fades and I romanticize the prospect of another one, so let me jump right to Saturday mid-morning, around mile 92, with 10 miles remaining. (On the elevation profile below, it’s the section on the righthand side between Long Lake and Mt. Werner.)

I was shuffle-jogging-hiking on a winding forested section of singletrack, my friend and pacer Amy behind me. The trail had ankle-rolling rocks and was a bit narrow and deep like a trench, but it wasn’t particularly difficult. In the frosty-cold middle of the night, we had tackled an arduous headwall made mostly of large boulders, where we needed to take snail’s-pace big steps while using our hands to pull up our bodies. This segment, by comparison, simply meandered relentlessly, with just enough turns and uphill slopes to disrupt any running rhythm.

“This is fine,” I told myself, borrowing a mantra used by the best-ever female ultrarunner, Courtney Dauwalter. I objectively could tell I was doing fine, and objectively this part of the course was easygoing, and the weather was downright lovely.

And yet, inwardly I felt wrecked.

Physically, the discomfort radiated from my stomach, which cramped and clenched from the aftermath of vomiting and dry-heaving 20 miles earlier. Despite my best efforts to be a good eater and stay hydrated with a just-right balance of food, fluid, and electrolytes, my fueling strategy failed, creating a gag reflex that made it virtually impossible to swallow anything.

The discomfort extended upward to the base of my neck, which felt so tight and tender I could barely hold my head upright; to my dry eyes, which kept rolling behind fluttering eyelids even though I willed them to focus; to my brain, which felt dizzy with lightheadedness.

Below my stomach, the discomfort snaked down to my gut, creating pressure to take a big potty break in the woods, but the prospect of finding a hidden place to dig a hole and do my business seemed far too complicated and time consuming to execute. My whole trunk and legs felt hot and bothered because I needed to shed my long-sleeve layer and nighttime tights, but the idea of stopping to take off my pack and do a wardrobe change also seemed too complicated. So I kept shuffle-jogging-hiking.

I could handle that moderate physical discomfort. The real problem was my emotional state. I felt increasingly despondent and frustrated.

My thoughts followed this line of questioning and negative conclusions: Why am I running 100s if, in the past four, I’ve fallen apart in the second half? I’m finishing this event to get a qualifier to enter the Hardrock 100 lottery, but if this easier 100-mile race feels this difficult only 20-some hours into it, how could I ever handle Hardrock, which will take 40+? I am completely calorie depleted. There is no way I could go past a second sunset and into a second night for the much harder Hardrock. I was so happy and running so well during the first 50 miles. Why don’t I stick to 50s? This should be my last 100. Is this how I want to finish my last 100?

“I need to focus on what’s going well,” I told Amy, to snap out of the downward spiral of thoughts. So we made a list out loud: my worn-out knee was behaving. In fact, all my lower-body joints and muscles were doing remarkably well, thanks to solid training, and therefore my lower body maintained strong forward movement despite the energy depletion. My feet felt OK. I did not succumb to trailside naps during the night as I did during last summer’s 100. Although my goal of finishing under 30 hours had slipped away (I was coherent enough to do the math realistically), I could still finish under 31. I still cared enough to hold onto that goal, which was something.

“I mean, you’re moving really well,” Amy kept saying, and then she returned to her enthusiastic chatter about the 100s and 200s she has done (like this one I wrote about earlier) and wants to do. Amy lives for these events. She voices the energy and enthusiasm I feel until everything devolves during the dark overnight.

“How many have you done?” she asked, probably to get me talking and distracted from discomfort.

I answered as if reading a grocery list. “I dunno, because the 100s are mixed in with buckles I got from the four 170-mile stage races, so, um, Rio Del Lago. Wastach. Western States. Two 24-hour events where I got to 115 miles in each. This Run Rabbit Run in 2017. High Lonesome twice. I think there was one more that was pretty forgettable. Oh yeah, Coldwater Rumble.”

“That’s nine. That means this is 10!”

Amy said “10” as if it were cause for celebration, but I heard it as one more reason to cap off this 100-mile folly with a round number. My internal voice continued: I don’t need to do Hardrock, and I probably won’t ever get into it anyway. I can get everything I want out of this so-called sport by doing shorter ultras. There’s just no conceivable way I could ever stay awake long enough and eat enough to get through something as long and hard as Hardrock. 200s? Forget it. No way I’m doing the Kerry Way 200K next September either. Why ruin a trip to Ireland with a race even longer than this? Let’s go to Ireland like normal people to hike and drink.

I was spacing out, picturing in my mind’s eye a stereotypical picture of Ireland’s rolling-green landscape next to coastline, not seeing the trail in front of me.

Suddenly, in a split second that I can hardly re-create because it happened so fast and inexplicably, my ankle turned under, and I slammed down on my butt and elbow. It was as if something had jerked my feet sideways and pulled me down, the force was so powerful. One second I was upright, the next I was crumpled sideways, yelping in pain and shouting the F word. Adrenaline surged through my limbs and made me hyper-aware of everything yet disbelieving, as if I had been drifting to sleep on a car ride and woken up by a sickening rear-end accident.

Amy gasped and shouted, “Are you OK, are you OK?” She told me later that she thought I had broken my ankle because of the angle and movement of my fall.

I could sit up and move my legs and feet, so nothing was broken or even sprained. I just felt body-slammed and punished and so mad at myself and the situation. One of my goals had been: no trip-and-falls. Blew that.

“This fucking sucks. I am so ready to be done,” I said, using my trekking poles for assistance to stand up on wobbly legs. Then I took a couple of tentative steps.

24 hours earlier, I experienced bliss

I have never experienced such a beautiful, peaceful, positive start to an ultra as I did with this race on Friday morning. The feeling carried me through the day.

This race, which has a rabbit theme due to a rock formation resembling rabbit ears on a mountain pass near Steamboat Springs, divides runners into “Tortoise” and “Hare” divisions. Some 400 regular runners—the Tortoises—start at 8 a.m. About 100 faster, competitive Hares, who are racing for a large purse of prize money, start at noon.

A little-known fact is the race has a tiny third division: the early-bird oldster Tortoises who are men over 60 and women over 50. We are allowed to start an hour early, at 7 a.m., and we have 37 rather than 36 hours to earn an official finish. It’s undeniable that we older runners, especially women, slow down significantly after 50 and more so after 60 due to numerous physiological factors. The race director created this early-bird division to encourage older runners to keep trying 100-mile ultras with reduced fear of getting timed out by the cutoff time. I think this is generous and brilliant, and like a senior discount, it recognizes and honors the contributions of older folks.

I did not need the extra hour to finish on time (at least, I hoped not); my plan was to finish in close to 30 hours, not the limit of 36. But I took advantage of the early-bird start because, why not? I’m 54, I earned it.

The morning got off to a smooth start because we booked a condo at the Sheraton right next to the start/finish line (a high-quality resort, highly recommended), which made getting up and to the start on time extra easy and low-stress. My son Kyle had driven from Boulder to spend the night with us, and he kept making me laugh. I was wearing a Black Diamond windbreaker with a steel-blue color, and when he looked at me with sleep-bleary eyes, he asked with genuine bewilderment, “Why are you wearing a trash bag?”

Outside, 15 minutes before the early-bird start, the starting area looked nearly empty. Thankfully, my friend Cara Marrs (another early bird) showed up, then a few others. Ultimately, I counted only six of us women and two men taking advantage of the early start. I knew several additional over-50 women and over-60 men would be racing today, but for some reason they had chosen to start with the regular Tortoises. Maybe they felt there was something shameful about getting a head start. Whatever, I was glad to be there, in our blissfuly uncrowded little pod of senior runners.

The race director counted down from 10, and we took off up the ski slope. I knew not to go out too fast, but man, I felt good! In spite of my conservative-feeling pace, a gap quickly opened between me and the others; only one 60-something man named Bill stayed close enough that we could exchange pleasantries.

The route gains over 3500 feet in the first five miles. We ascend up a windy singletrack trail that spits us out on a wide ski slope. Going up that trail, I kept thinking about how the regular 400-person Tortoise start would create a conga line of runners stepping on each other’s heels, noses pressed into backs, and I felt suffused with gratitude and awe that I could stride up virtually solo. I also felt gratitude and awe that this steep ski slope to the top of Mt. Werner’s gondola felt relatively manageable, thanks to training on Telluride’s ski slopes.

The overcast sky lightened, I shed my windbreaker, and when the ski slope transitioned to rolling singletrack, I ran a smooth-flowing pace that felt close to effortless. Whatever might happen later in the day or night, my God, I was loving this first portion of the race, when I had the scenic trail to myself with fresh legs.

Mantras—sayings to repeat in my head, in rhythm with my stride—always come to me; I don’t plan them ahead of time. This time, a mantra emerged as: be calm and confident. Then I worried I was being too cocky with feel-good freshness. I could trip, I could go off course. An old saying goes, “You can’t win an ultra in the first half, but you can lose it” due to careless mistakes. So I modified the mantra: be calm, be careful. Then I added, be calm, be like Courtney.

For nearly four hours, I ran blissfully by myself. The downhill trail around mile 14 became extra rocky and technical near the scenic and popular Fish Creek Falls, and I passed hikers who stepped aside and made encouraging remarks. It wasn’t until about a mile before the second aid station, around mile 17, that the lead two guys from the main Tortoise start caught and passed me.

The second aid station is accessible to crew and spectators, and as I followed those leading two guys into it, throngs of people erupted into cheers for us. They kept shouting at me, “First woman, third overall!”

“Oh no, no, I’m an early starter, they’re an hour ahead,” I kept clarifying.

“Still, you’re crushing it!”

I admit, it was fun albeit illusory to be in the lead like that. I felt like a rock star. I knew I was running well and primed for a good day.

The positivity persisted throughout midday and afternoon, as more Tortoises from the main start caught and passed, and I enjoyed their company. The weather—rainy the day prior—stayed dry but not too warm. Nothing went wrong, everything went according to plan. I had developed a detailed race plan with help from the wise and experienced Olga King, with goal splits to each aid station, and I was always within 10 minutes of hitting those splits.

I also was meeting my goal of getting in and out of aid stations in less than five minutes, then allowing myself a full 10 minutes at the mile 30 Summit Lake aid station, where I had a drop bag. In that bag, I packed a shaker cup, spoon, and packet of GU Rocktane recovery drink mix so I could make a protein/carb shake with 250 calories. It tasted great and went down easily. I was being mindful to eat about 200 calories per hour—nibbling on a snack every half hour—and then take in extra calories at aid stations. I also was staying well hydrated with Scratch hydration/electrolyte mix. So far, so good.

The race plan with goal splits kept me motivated. I got to the mile 44.5 Dry Lake aid station right around 6 p.m. where I met my first pacer, Cristal Hibbard, and we shared six lovely, smooth miles into downtown Steamboat Springs at sunset, marveling at the golden glow of the trailside ferns.

The fueling fail

Last week, I published a bonus post for paid subscribers detailing my fueling and hydration plan. The gist of it was, I gave up GU gels because the syrupy-sweet gel backfired in my last several ultras. I would still get some simple sugar (mainly sucrose and dextrose, not fructose) from the hydration mix and snacks like Honey Stinger Waffles and some yummy cookies I carried, but I’d rely more on starchy carbs (like Ritz peanut butter crackers and potato chips) and a variety of real food. For some reason, over the last few years, I started to gag on gels (and yes, I tried alternatives to GU like Maurten but didn’t like them either).

As Cristal and I approached the main crew meeting point of Olympian Hall, mile 51, at twilight, I looked forward to seeing my husband Morgan and other pacer Amy, and to eating the cup of mac & cheese I had bought for them to make with boiling water. I met them still feeling fresh and positive, proud to be running and functioning well. I told them I wanted to be in and out within 15 minutes, so we all acted business-like.

Morgan broke the news that the cup of mac & cheese, along with the noodle soups that I had bought, all needed to be microwaved; hot water alone wouldn’t cook them properly. Only the instant mashed potatoes worked. I was disappointed, but the instant potatoes tasted good enough, and I ate a whole cup. Amy brought me a quesadilla from the aid station, but I disliked how they used processed cheese rather than real cheese—it tasted gross—so I told them no thanks. I took an avocado/cheese tortilla rollup they had brought from the condo and put it in my pocket to eat later.

I was focused mainly on my goal of getting in and out of that aid station in 15ish minutes, and I wanted to get going before catching a chill and feeling stiff. In hindsight, my unwillingness to take time for a more restful break may have set me up for trouble later.

Wearing headlamps and an extra layer for warmth, Cristal and I left Olympian Hall around 7:50 p.m. for a loopy, hilly 13-mile portion that follows a baffling network of trails with names like Blair Witch and Lane of Pain. I felt grateful for Cristal’s company and navigation. Hiking up the first hill, the lead Hare runners passed us, and I marveled at their uphill running prowess.

About an hour into this portion, I realized I should eat, so I pulled out the avo/cheese wrap and took a bite. Uh-oh, it tasted unpleasantly sour, as if it had gone rancid, though I knew it was fresh. I recognized from experience this was a sign my palate was starting to rebel. I managed to eat half—about 150 calories—but didn’t like it.

We made it back to Olympian Hall, mile 64, around 11:40 p.m., and I felt overly preoccupied with getting out of there before midnight, which would keep me close to my goal splits. I also cared more about my wardrobe change than eating. I took off my shoes, and then Amy and Cristal held up a blanket on one side of me, a beach towel on the other, so I could strip out of my shorts and put on warm tights and fresh socks. I added a puffy jacket, thick gloves, and a buff for head warmth, and strapped Kogala lights to my sternum strap in addition to my headlamp.

I was ready for the darkest, coldest hours! Eating, however, became an afterthought. I ingested some spoonfuls of mashed potato, and loaded up my pocket with snacks, but didn’t actually eat more than maybe 100 calories at that critical aid station stop. In hindsight, I could’ve paused and gone inside the building, where it’s warm, to have something more dinner-like.

Amy and I began fast-hiking and jogging on the path leading out of town, and I settled into a steady hiking pace as we made our way up some 1500 feet back to the Dry Lake aid station, mile 70. The first real wave of fatigue washed over me, in part because the energetic feeling from the busy aid station wore off, but also because of calorie deprivation. I knew the uphill portion between miles 70 to 80 would be one of the most technical and challenging of the course, so I must eat well at the next aid station.

At mile 70, the Dry Lake aid station, they offered the perfect snack: thick ramen noodles in chicken broth. I took a cup, took a seat, and eagerly put a forkful of soft, wound-up warm noodles into my mouth. It tasted good and went down easily. I had no idea a bomb would explode.

The minute those noodles hit my stomach, nausea involuntarily forced my head down between my legs. My mouth opened, and a wave of liquid and chunks splattered on the ground between my feet. It took me utterly by surprise. Then it happened again—another wave, but this time smaller. Then a third time, but mostly a dry heave.

I sat there gasping and disbelieving, but also, feeling a bit better. I took deep breaths and decided to try again—a little sip of broth, a little bite of noodles. Uh-uh, nope, no way, gag. My stomach wouldn’t take it.

“Let’s go,” I ordered to Amy and to myself. “I’ll have some ginger ale later and be OK.”

Should I have waited there longer to reset my stomach? Perhaps. But I knew for certain that it was freezing cold, and at least I could move to prevent a chill. So we soldiered on toward arguably the most difficult part of the course—between Dry Lake and Billy’s Rabbit Hole (mile 76)—on a route made largely of granite painted with hash marks to direct mountain bikers. This apparently is an advanced mountain bike route. I kept wondering, how the hell do bikers ride down these massive rocks? They must have a death wish. How the hell do I get up them? Maybe I have a death wish, too.

“Billy will have pizza,” I mumbled, and Amy asked me to explain. The remote aid station at mile 76, staffed by Billy and Amanda Grimes, set up a pizza oven and served delicious pizza when I passed through earlier in the day at mile 34. I made a pact to eat pizza. I always like pizza.

We finally got there at God knows what time, maybe 4:30 a.m. I took a seat next to a roaring campfire while Amy asked if they had any pizza left. They did! It was cold, but I didn’t mind. I grabbed the triangle slice and committed to a big bite.

Morgan and I have the same conversation about red chili flakes every time we eat pizza. I tell him he ruins his pizza with them. He tells me I’m missing out. But I can’t tolerate spicy food.

Instantly, this pizza lit my mouth on fire. Apparently, it was covered in red chili flakes. I spit it out, cursed, gasped, and took sips from my bottles. But the heat only intensified in my mouth. I thought I’d be sick again, and my torso jerked as if dry-heaving. Amy got me ginger ale to rinse, and I took a sip, but that carried the spiciness further down my throat. She found a plain piece of pizza for me to try. “I just can’t,” I said. I was screwed.

We left and headed toward the next aid station at mile 80, Summit Lake, where I had my drop bag. I can’t recall anything from this section except for feeling sleepy, lightheaded, and getting passed by more runners. I held onto the hope of daybreak and the fact that my drop bag contained one more of those 250-calorie recovery shakes.

The pile of drop bags in the light of dawn looked white, every bag and everything around it covered with frost. I got out my cup, spoon, and GU Rocktane recovery mix. I found a chair next to a portable heater and made the shake, then took a sip. Hallelujah, it tasted good! It felt good! I drank the whole thing. I could’ve used a second one. Live and learn.

Those liquid calories gave me a boost, and Amy and I enjoyed a relatively pleasant and stronger 10 miles in the early hours of the day. I turned my Spotify playlist on and let it play out of the speaker on my phone, so we could enjoy the music together.

I wasn’t too far off my goal pace, and I was moving better. I was able to eat some of the Ritz peanut butter crackers in my pocket, and half a banana at the next aid station (mile 89), along with ginger ale.

“This is fine,” I reminded myself. “I’m going to finish.”

But with each hour, the trail seemed more monotonous and interminable, my body more hot and bothered and achy. My alertness faded to deeper fatigue. My mind slipped into the negative thoughts described in the opening scene above. I became convinced that 50-milers and 100Ks make much more sense than this 100-mile purgatory.

Flatlined

When we finally, finally, reached the final aid station with a little over six miles remaining, Amy got teary from feeling some mixture of happiness and admiration for me. She actually was blinking back tears and trying to rein in her emotions. She’s so kind and caring.

I, by contrast, felt emotionally flatlined. Not angry, not eager, not anything, just on autopilot. Ready to be done. I looked around at the ski resort access road, where the morning prior I had hiked and run up here so full of energy and joy—first one up the mountain!—and tried to rekindle some of that bliss and awe. Nope. No sugarcoating it, this last downhill portion descending nearly 4000 feet was gonna hurt and suck.

Every step, magnified by downhill impact, radiated pain. It hurt my feet, my knees, my quads, my hip flexors, my lower back, my shoulders, my brain. I wanna be done, done, done. I could run a minute, but then I needed a 30-second walking break. I got in a rhythm of run-walk intervals, and we gradually made it down that long dirt road.

Cristal rejoined us for the final quarter mile. I felt a flicker of satisfaction and appreciation for these two women’s support and kindness, but mainly, I felt drained and flat, almost robotic.

There’s the crowd. There’s the finish-line arch. There’s Morgan. Run, run, run. Cross the timing mat. Get a hug from the race director. Get a hug from Morgan. Mumble thanks. Need a chair. Sit. Amy’s crying now. I can’t relate. I feel nothing except some relief and the sense that I might pass out.

It’s crazy how emotional a 100-mile finish can be, as described in my last 100-mile race report, when I had an epiphany about my life’s purpose and experienced perhaps the deepest-ever level of love and physicality in my adult life. And it’s crazy how, this time, I felt close to nothing besides fatigue. Maybe even a sense of pointlessness.

I sipped a carton of chocolate milk at the finish line. It made me feel better, as did an impromptu chat with third-place Hare finisher Arlen Glick, who was hanging out and ridiculously nice and friendly. He told me everything that could go wrong with his race did. It felt good to feel curious about someone else instead of being single-mindedly focused on finishing my race. I suddenly wanted to get on my phone and learn about how the race had unfolded for others.

I walked the short distance back to our hotel room, took a shower, and instantly fell into a deep sleep.

Only after that nap did I begin to feel some warm-fuzzy feelings of pride, accomplishment, gratitude, and happiness for finishing in 30:47 (results) and experiencing so many sights, feelings, and human interactions along the way. Replenishing calories certainly helped my mental and emotional state.

I am not ready to say “never again” to 100s. I realize now that training for this 100-miler structured my summer in a wonderful way—from kicking off the training block with the big Grand Canyon run in May to doing the Telluride Mountain Run 40 three weeks ago—and that 100s are a long, special process, not just a 24-to-36+ hour event. I also realize that if ever I get the opportunity to do something more difficult (i.e., Hardrock), I must treat it like a journey, not a race, and let go of any adherence to goal split times or a goal finish time.

Then again, 10 is a nice round number.

Thank you for sharing the emotional side of your experience! We all read the race reports that talk about the terrain and triumphs, but I'll take the real stuff any day!

Nice running with you the first few miles, good luck on the hardrock lottery. I knew you'd finish ahead of me, but wasn't thinking it would be 5 hours... See you for the early start next year? It's nice having the course to ourselves. -Bill