What Makes a Good Ultra

Certain qualities that you can cultivate for a better long race or any big project

Hello and welcome back! I took that photo above on Saturday morning as the sun rose just after 7 a.m. and illuminated an alpine basin above Telluride. I was approaching a mountain pass above 13,000 feet in the early miles of the Telluride Mountain Run 40 race. My day—the whole experience—was off to a very good start.

I’ll describe what made it a good race in spite of a surprise ending and what constitutes “a good ultra” below. But first, I have a request.

If you’re a subscriber (not a one-time visitor), I’d deeply appreciate if you would fill out this reader survey. I’m approaching the second anniversary of this newsletter and need to know, what’s working about it, what’s not? How should I continue to develop it? Your feedback is very valuable to me. The survey is short and should take five or so minutes to complete. As an incentive, I’ll draw two respondents at random to win an item of their choosing priced at $20 or less from the semi-rad.com store (which is full of fun stuff). Please reply before September 18, thank you.

I met my husband Morgan near mile 30 at the penultimate aid station in the Telluride Mountain Run, and afterward, he kept commenting, “You looked so happy … you looked so strong … I could tell you were fine” in spite of strong rain soaking through my windbreaker. Those were the best compliments, and how I hope to feel and run in two-and-a-half weeks at the Run Rabbit Run 100 in Steamboat Springs.

Our success at a long-distance race, or any endurance endeavor, depends so much on mood and emotions. I’ve been trying to dissect why I felt good on this run, and how I can replicate that state of being for the 100-miler—or for any big challenge or project in other realms of life.

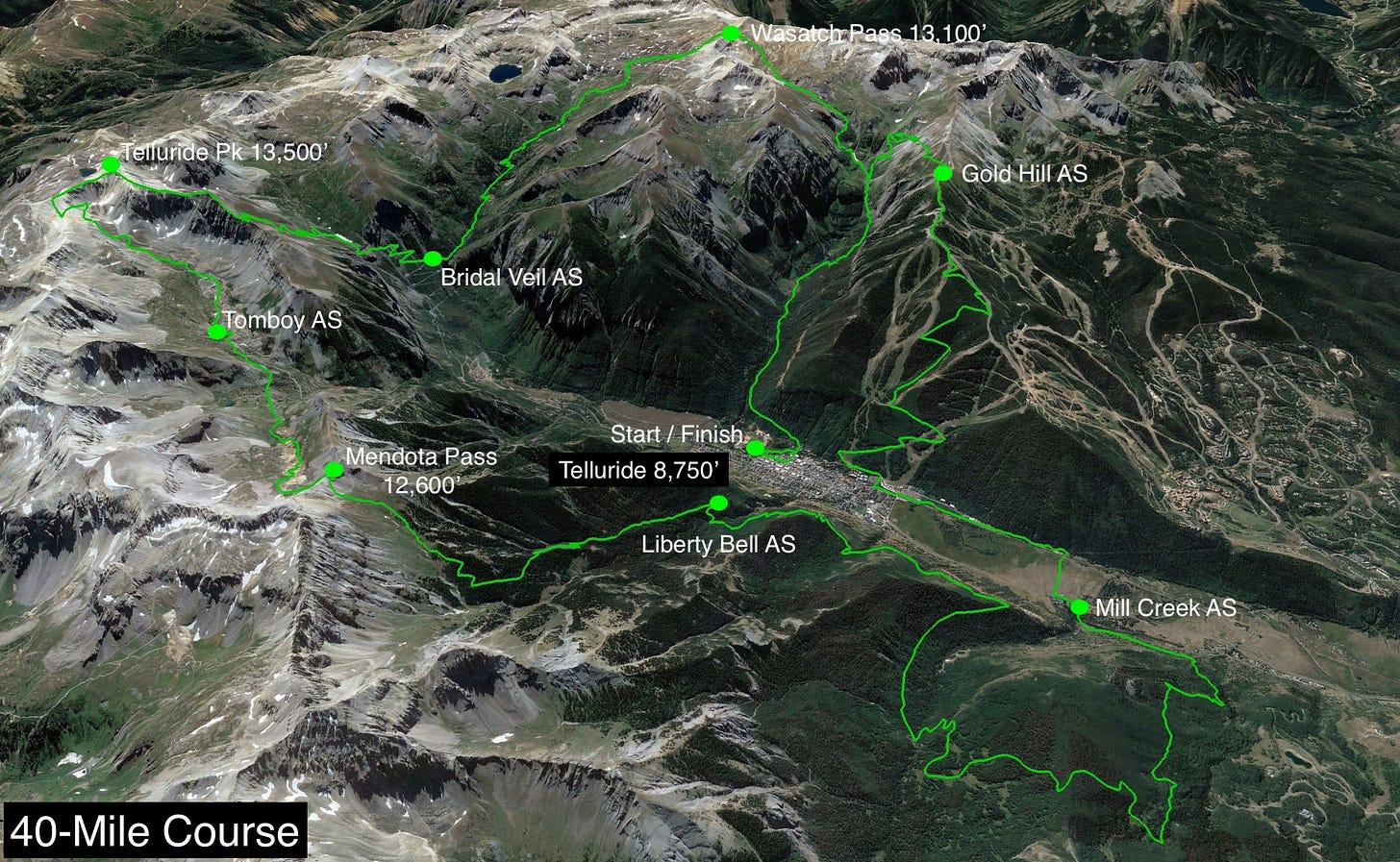

First, some context: The Telluride Mountain Run 40 is a doozy of a tough ultra, with mountain passes and terrain covering a couple of segments of the Hardrock 100 course. It’s comparable or tougher in difficulty—in terms of vert and duration—to the San Juan Solstice 50, despite being 10 miles shorter. The route forms a giant loop around Telluride, traversing four major mountain passes—two above 13,000 feet, the other two above 12,000—with elevation gain for the 40ish miles totaling over 13,000 feet. In certain miles, the terrain is so rocky, exposed, and steep that one’s hiking pace can slow to 30 minutes/mile or slower, so averaging a mere 3 miles per hour (20 minutes/mile) on this “run” constitutes a respectable mid-pack pace.

We started in the dark and legs felt fresh, spirits high. I chatted with runners around me and played tour guide to those who were new to the area. I didn’t feel pressure or stress because I wasn’t competing with others; I had clear goals that had nothing to do with those around me. Those included:

run smart as if in the first half of the 100-miler in order to reach the end feeling as if I could keep going

hydrate and fuel to prevent dehydration, nausea, and bonking

stay relaxed and positive

avoid tripping and falling or rolling my ankles

(stretch goal) if I’m feeling good, then push to meet or beat my time on this route from 2021

In other words, on this run and in most races, I try to do my own thing—compete with myself and my watch to achieve personal goals—rather than compare myself to others and judge my performance on how I finish in relation to them. (Often this is easier said than done, because I’m competitive, but I try.) Racing others—trying to catch, pass, and gap someone—certainly can be motivating, exciting, and is the heart of competition, but I’m suggesting that it’s helpful to view the competition with others as secondary to your individual plan. “Run your own race, go your own pace,” is a saying I always told my coaching clients and tell myself.

Sunrise illuminated the beauty of the high-alpine terrain and mountain ridges, and the early morning sun’s slanted light saturated the yellows, blues, and magentas in wildflowers. I buddied up with someone on the first long downhill, a runner from Virginia, and we realized we had a mutual friend and a lot in common (especially our shared interest in the Hardrock 100). The miles rolled along like the conversation. It was one of several conversations I’d have during the day.

I fueled up at the first aid station (Mile 11, above Bridalveil falls) and began switchbacking up the next major climb to the toughest portion of the route: the 1.5-mile fin of a ridge line made of chunky, wobbly rock, which links Ajax Peak to Telluride Peak and then descends to Imogene Pass. At certain places, rock outcroppings interrupt the thin ridge, so you must figure out the best way to scramble or climb over or around the sharp-edged boulders, pieces of which sometimes break off and threaten to hit runners below. Looking down the drop-offs can spark vertigo and fear, so it’s best to keep eyes forward, concentrating on where to take the next step or grasp a handhold.

I moved steadily and calmly, experiencing little of the fear that gripped me the first time I traversed this in the 2018 edition of the race. Partly, the weather calmed me—I lucked out and made it across the ridge before the good-weather window closed. Later in the day, lightning would threaten anyone up there, and rain would make the rocks slippery. But mostly, I felt confidence that came from experience. I actually am better at handling these kinds of high-mountain scrambles because the more I do, the more comfortable they feel.

Check out this Instagram post’s photographs, showing the lead runners traversing the ridge, to get a sense of what it was like. I was too focused, and using my hands, to take photos along the most difficult ridge sections.

Heading down from Imogene Pass to the Tomboy Mine, I felt the first real twinges of discomfort bordering on pain coming from my left knee (which has worn-out cartilage diagnosed as chondromalacia) and lower back. I looked forward to the next big climb to reduce the impact. The pain returned, along with discouragement, on the next long downhill midway through the route. I adjusted my stride to make each step more gliding than hammering and tried accept and manage the negative feelings.

After the third aid station, around Mile 22, the route finally gave us more opportunities to run steadily with cruising segments below treeline. Being super familiar with these segments, I challenged myself to run each runnable portion and limit my hiking breaks as much as possible. I passed several others to whom this meandering forested section probably seemed relentless. I thought ahead to the Run Rabbit Run 100, which features many miles of forested singletrack like this, and tried to practice how I hope to feel and run there.

In the aspen grove, on the route’s long traverse to the west end of Telluride, the clouds thickened and unleashed rain, which felt pleasantly cooling after the humidity that preceded it. I didn’t mind the rain, as long as I kept moving enough to stay warm and as long as electricity in the sky didn’t threaten us.

After meeting Morgan at the second-to-last aid station, around Mile 30, I felt determined to make the most of the easy-running section across the Valley Floor before the final monster climb up the ski slopes. Although my legs expressed stiffness and fatigue on the flat path, after all those sharp uphill and downhill miles, I settled into a steady pace.

With satisfaction, I looked at my watch and realized I was on pace to match my 2021 time of 13.5 hours, or a 19 minute/mile average pace over the 42ish miles. I knew the final climb of nearly five miles with 4000 feet of elevation gain would slow my hiking pace to around 22 to 25 minutes per mile, so I pushed to bank more time on this runnable part.

Once I reached the Telluride Trail, which zigzags up the mountain next to ski slopes, and then transitions to the See Forever Trail, the rain developed into a full-blown thunderstorm endemic to San Juan Mountains’ monsoon season. I put on my waterproof rain jacket and then added a cheap plastic poncho for an extra layer to trap body heat, since I felt my hands growing cold. Preventing a chill and the stiffness that comes with it became paramount.

Lightning flashed and split the sky overhead, followed immediately by deafening thunder. Again and again, the sky flashed light and boomed with thunder claps that sounded like rifle shots. But a pine forest lined the See Forever Trail—I wasn’t quite above treeline yet—and the forest canopy made me feel safe, so I kept ascending with a handful of others in the race. They looked grim—one guy visibly flinched each time lighting and thunder erupted. When we paused to talk to each other, I tried to reassure them that we were OK in the forest and that the dark clouds seemed to be moving in a good direction, indicating the storm was passing. We’d be OK once we got to the top, I predicted.

Strangely, the more the weather conditions deteriorated, the more emboldened I felt. I actually was enjoying myself because of feeling strength and determination. This is amazing, I thought. The extreme altitude, terrain, weather, beauty—all of it filled me with awe along with gratitude that I get to spend a day in the mountains, circling my home town, like this, and that my body—the oldest female participating—could handle it. I wanted to nail this final section so this day would be a confidence-builder for the upcoming 100. I felt I was on my way to finishing strong.

And then, suddenly and unexpectedly, it ended.

The surprise ending and unusual results

Just after Mile 34, as I was cresting the See Forever Trail where the trees thin out and the ski resort structures start to appear, a couple of female runners ran toward me.

“Race is over! We’ve gotta go back down!”

What? But the clouds seemed to be lightening, the storm passing.

“The race director called it off for safety,” they explained to me and the handful of others nearby. “We need to get off the mountain, and they told us to go back this way. We can’t go over Gold Hill.”

I found out later from my friend Rick Simonson, who was the captain at the final aid station atop the very exposed Gold Hill overlooking the ski resort, that a bunch of aid station volunteers and runners squished together inside his Yukon SUV for safety for over a half hour during the worst of the lightning storm. He was in communication with the RD Jared Vilhauer about the unsafe conditions at the summit, and Jared canceled the race at around 3:45 p.m. Even if the storm passed (which, it turned out, it didn’t for a few hours—the thunderstorm persisted), it was unsafe for runners to continue on the route with the final aid station dismantled.

I briefly flirted with the idea of sticking to the route, because I felt comfortable with the risk of getting over the final summit and descending via the trail in the Wasatch Basin back to the finish line. Then I snuffed out that idea. Over the years of participating in ultras, I’ve learned: (1) respect the RD’s decision, especially a safety call; (2) runners should not “go rogue” by going off on their own mid-ultra, because then the race organizer can’t keep track of them, which creates headaches and safety risks and also can jeopardize the event’s permit; and (3) don’t be a complainer.

So I turned around, feeling deflated—I really didn’t want to run back down the way we had just come up—but I felt more sorry for the runners around me, who were from out of state and wanted their hard-earned finish. For me, this was just a training run, not a goal race, and I’ve done this route before and can do it again. For them, this was a special destination and opportunity.

We turned around, saying things to each other like, “safety first,” “weather happens,” “we’ll still get close to 40 total” and generally trying to make the best of running back to the finish while knowing we wouldn’t earn an official finish.

I crossed the finish line just over 12 hours, having completed 38 miles. I felt happy and generally satisfied, in spite of the shortened route—except for one thing. It really bothered me that my result in Ultrasignup would be listed as a “DNF.” It seemed that race directors have only three options for listing results—Finishers, DNF, and DNS (did not start).

Only 20 speedy runners, out of 95 starters, finished the 40-miler before the race cancelation. Seventeen of the starters were true DNFs, meaning they dropped out voluntarily mid-race or missed a cutoff. The remaining 58 of us were ahead of cutoff times and intending to finish. It didn’t seem fair that we’d have a DNF on our record.

Admittedly, and perhaps somewhat ridiculously, I care about my Ultrasignup results the way some people care about their LinkedIn—it summarizes my accomplishments, and out of 100+ races to my name, only two are DNFs. I regret both those DNFs (from the 2015 Gorge Waterfalls 100K and 2018 Ouray 100) and make a point of entering every race with a mindset, “commit not to quit.” I won’t DNF unless faced with a true medical or safety issue. I really didn’t want this Telluride Mountain Run—which felt so positive and well-executed—to end with a DNF.

Thankfully, this story has a good ending, because the race director shared my point of view and came up with a work-around. Instead of listing us as DNFs, he listed all of us who got pulled from the course as “unofficial finishers,” and gave us the same time—10:45, approximately the time of day when he ended the race—so that the listing won’t affect our Ultrasignup rankings. I thought this was a thoughtful way to handle the tricky situation, and I appreciate having this “unofficial finish” instead of a DNF. You can see the results here.

To recap, these are some of the things that made this ultra feel so good—and, likely, enhance any undertaking, be it athletic or part of everyday life.

personal goals that are separate from how you rank and perform relative to others

motivation, not ambivalence or complacency, which comes from setting and chasing those goals

connection and camaraderie with others, creating a feeling of belonging and shared purpose

confidence and courage that come from preparation and experience, and which lead to a “flow” state of focus and execution

acceptance of limitations, discomforts, and setbacks

Reflecting on this run, I realize it felt manageable, and I didn’t suffer beyond normal fatigue and discomfort. Midway through the run, I listened to this short pre-UTMB interview with Courtney Dauwalter for inspiration. In it, she talks about her metaphorical pain cave that she enters with a mindset of curiosity, rather than resisting it.

Hearing her during the run, I asked myself if I was going too easy—if I wasn’t pushing enough—but I concluded no, I feel good about the effort level. This 40-miler wasn’t my goal race; its purpose, three weeks before the 100, was to practice a manageable, sustainable pace and prevent or troubleshoot problems. I’m fairly certain I’ll enter that metaphorical pain cave in the second half of the upcoming 100-miler. Having a smart and manageable first half will make me better equipped to handle fatigue and problems in the second half, at least I hope.

Competing at 80

I want to end with a shout-out of congratulations and admiration for Doug Barrows, a paid subscriber to this newsletter who’s a regular on our monthly Zoom. He recently celebrated turning 80 by finishing a 30-mile trail race called Lean Horse in South Dakota, just a few days before his birthday. He wrote me advice on how to compete at 80, which I’ll be sure to follow in 26 years:

Basically, find an ultra-distance race that has a cutoff time no more than two hours less than what you think you can do. Then stay ahead of that time. The race crew is going to be at the finish line until then anyway, and if they really had a hard time with being there that late, then next year the cutoff will be three hours less than you think is doable. After a while, you recognize that there is a nickname for you and your initials are DFL. Smile and enjoy.

Please remember to take the reader survey! And please subscribe if you haven’t already.

The chase for that feeling of gratitude and strength you describe in the middle paragraph, just before the cancellation, is one of the main things that keeps me running. The fact that you got there at the peak of your last big run before Run Rabbit should set you up well for the race.

(And I don't think caring about your Ultrasignup is ridiculous – but if it is, a lot of us are ridiculous in the same way.)

Ultras at 80 sounds amazing!!!! I agree too that if a race gets called off it shouldn’t be a DNF. Can’t wait to hear about the 100, and Courtney.,.. not even possible