The "Wild & Tough" San Juan Mountaineers

A brief history of Dwight Lavender and his badass climbing buddies in the early 1930s

Many thanks to all who left supportive comments or emailed me thoughtful notes after my last personal post. Now, to refocus on the mountains, I’m excited to share a slide show and history lesson.

This is Part 2 of a presentation I gave with climber and historian Pete Davis last July in Silverton to Hardrock 100 runners. Race Director Dale Garland asked us to talk about regional history to enhance appreciation of the route that Hardrock runners traverse and to fortify them to be “wild & tough” (the Hardrock motto). I gave Part 1 of the talk about surveyors, prospectors, and miners who blazed trails in the San Juan Mountains from the 1870s through early 20th century. I also wove in some family history, since my great-great-grandfather through grandfather lived through those times here in Telluride. I hope you’ll read Part 1 and enjoy those photos too.

Thanks to Pete Davis, we have the following stories about the San Juan Mountaineers. Pete is an accomplished climber (check out this awesome short documentary about him and two other amputee climbers), and he’s also operations manager at the Ouray Ice Park. I connected with Pete, who lives in Ridgway, several years ago because he was delving into mountaineering history and focusing on my great-uncle Dwight Lavender.

Dwight—a year younger than my grandfather, David S. Lavender—left an incredible legacy as a climber, surveyor and map-maker, writer, photographer and even illustrator before dying at only 23 in 1934. It wasn’t a climbing accident that got him. Ironically, it was his supposedly safe decision to return to academia. He went to Stanford to pursue a graduate degree in geology, caught the polio virus, and died of paralysis in less than 72 hours. Lavender Col below the summit of the 14er Sneffels, and Lavender Peak in the La Platas northwest of Durango, are named after him.

What follows is a slightly shortened version of Pete’s remarks in direct quotations and his slide show. If you want to see more historical photos, CU Boulder’s Special Collections has digitized Dwight’s photo albums and you can browse them here.

Pete picked up where I left off, talking about how members of the Hayden Survey in 1874—including A.D. Wilson and Franklyn Rhoda—developed mountaineering techniques in order to do their work. “Their goal was mapping and surveying the area, so they had to gain the high points in order to triangulate off other high points, in order to create maps, accurate elevations, benchmarks, and whatnot. So they made several significant first ascents here; they climbed Sneffels for the first time, Uncompahgre Peak, Wilson Peak, Lone Cone, and more. … They basically opened the door for these guys, the San Juan Mountaineers.”

“Here are three main members of the San Juan Mountaineers: Dwight Lavender on the left, Chester Price, and Forrest Greenfield. The San Juan Mountaineers were a loosely affiliated group, and they met through a summit register on Uncompahgre Peak. Chester Price left a note in the summit register saying, ‘If anybody is interested in climbing the San Juans, contact this guy, Dwight Lavender, and here’s his address,’ and sure enough Mel Griffiths came upon it, and he wrote to Dwight and Dwight wrote back, and they all met up. This is their first trip together, up to the Wilson basin, in 1930.”

“This is Dwight Lavender here, a handsome fellow. He was definitely the ringleader of the San Juan Mountaineers. He was born in Telluride in 1911, his brother was David S. Lavender, and he comes from the founders of Telluride, the Painters. Charles Painter was first mayor of Telluride.” [Our Lavender surname comes from their stepfather, the rancher Edgar Lavender, who adopted my grandfather and great-uncle after their mother divorced David Painter and married Ed.]

“Dwight was amazingly prolific for his short time on earth. He unfortunately died at the age of 23, which was a devastating blow to the San Juan Mountaineers. In his short time, he was their passion and inspiration. He wrote this climbing guidebook, The San Juan Mountaineers’ Climber’s Guide to Southwestern Colorado, in 1932. He typewrote the book, drew the maps, and did so much work for that book while at Stanford University that nobody knows how he made straight A’s and over the winter created the book. He died of polio way before his time.”

“This is El Diente here, and Dwight got to name a 14er, which was a very rare thing by 1930. Almost all the 14ers had been climbed, and in this photo [the one above of Lavender, Price, Greenfield], they had just climbed El Diente. They thought they were getting the first ascent, and he had already come up with a name because it looks like a tooth. Then a few months later, after doing some diligent research, he realized that actually somebody else had climbed it before them. A British guy named Percy Thomas in 1890 had come out, and Dwight dug up a British mountaineering journal that describes it. But there was error in Percy Thomas’s thinking. Percy thought he was on Mount Wilson. It was a cloudy, rainy day, and the peaks were socked in, and he couldn’t see the higher Mount Wilson just a mile over. So he was sure he was on Mount Wilson, when in fact he was on El Diente. Dwight figured it out because Percy said, ‘I could see the peak of Mount Wilson clearly from Dutton Hot Springs,’ and Dwight said, ‘You can’t see Wilson from Dutton; you can see El Diente though.’ So Dwight came up with a compelling story that it had been climbed before, but because Percy Thomas didn’t know what he was on, they got to name it.”

“This is David Lavender [Dwight’s older brother and my grandfather], on Coxscomb Peak [a Class 5 13er close to the 14er Wetterhorn near Ouray]. His first book, One Man’s West, is super fun and comedic, an amazing account of Depression-era southwest Colorado. He went on to write 40 books about the West… He also joined Dwight on many of the expeditions.” [Note: Grandpa’s book One Man’s West has a terrific chapter called “High Altitude Athletics” that describes the San Juan Mountaineers.]

“This is the north face of Sneffels, a photo Dwight Lavender took, and this is their favorite mountain arena. They did about five first ascents on the north face, and this was a big deal for 1932. These were huge alpine routes. They did the east couloir and the central couloir by two different routes—one was where Sarah’s grandmother Brookie joined them to become the first woman ever to climb Sneffels via a new route.”

[According to my dad: “I heard many times that as they neared the summit, my mother slipped and fell fifty feet or so before the rope caught her. She said she literally saw her life flash before her eyes.” I wrote about her Sneffels summit here.]

“This is on the north face, their first attempt on the East Couloir in 1931, and that’s Mel Griffiths in front, Charles Kane, and Gordon Williams. As you can see, they’re climbing an ice field. This is below the main headwall. They had to chop steps into the ice because they did not have crampons at this point. Crampons weren’t invented. They had nails in their boots, but that wasn’t really adequate for ice climbing.

“These are really cool hand-colored photographs. You can see they left an incredible record of their time in the mountains, between the photography, the writing—they frequently contributed articles to Trail and Timberline (the Colorado Mountain Club magazine) and the American Alpine Journal—and they were really into getting people into what they were into. They knew they had something here, and they wanted to let people know about it.”

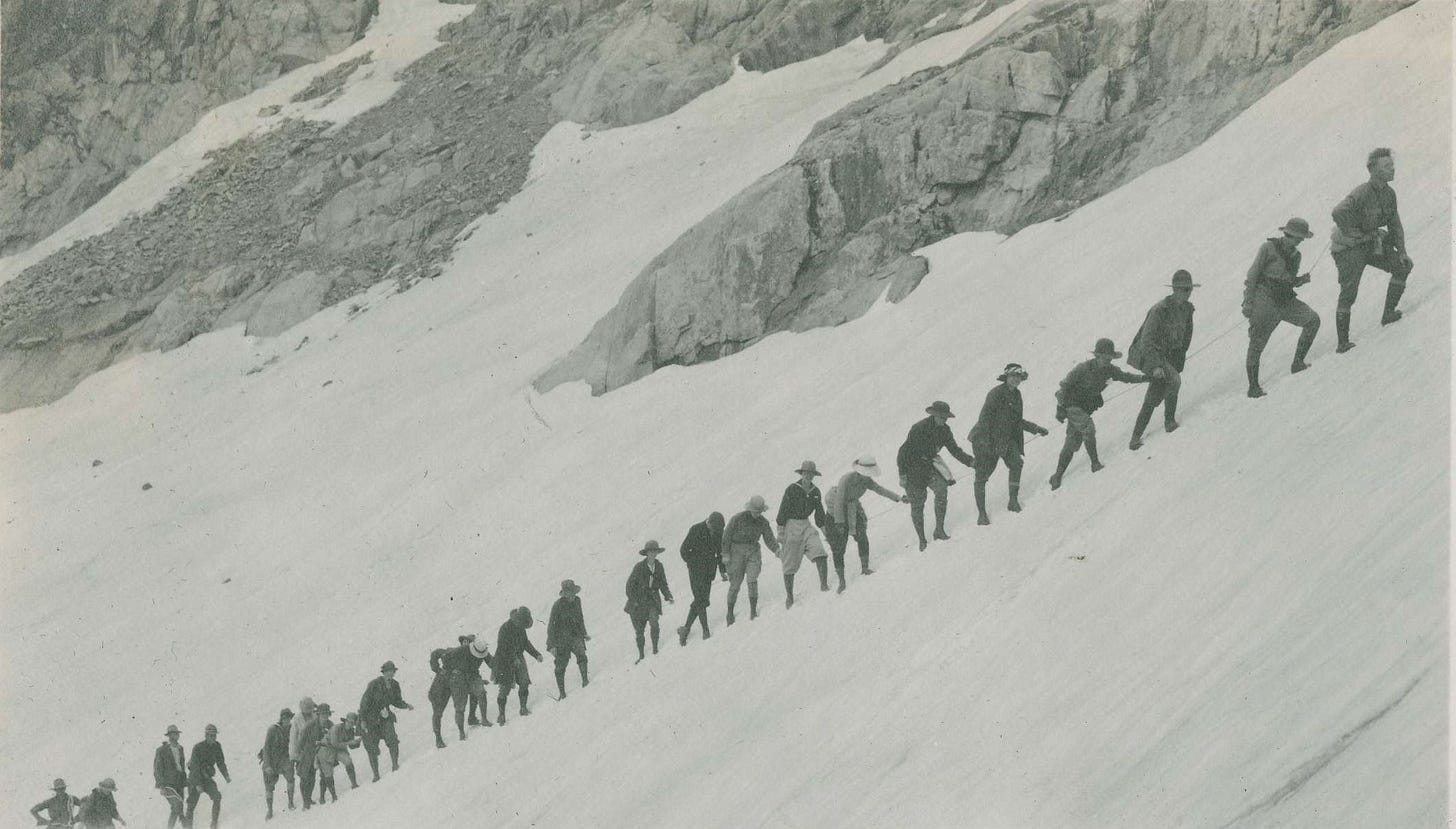

“This is an earlier Colorado Mountain Club expedition [on the 14er Eolus in 1920]. The Colorado Mountain Club really were the first ones climbing in the San Juans for recreation. They were massively focused on 14ers. The whole mindset of the day was, ‘It’s gotta be a 14er, or it’s nothing.’ Dwight realized that this was just absurd, to be focusing on the 14ers, because there’s so much more out there.

“Dwight wrote in Trail and Timberline, ‘We’ve got to get rid of the absurd idea that there must be at least one 14,000-foot peak offered on the CMC outings. It happens that the spectacular, hardest, and most interesting climbs are not always the big peaks.’ Which is so true around the San Juans. In the same article, he even referred to some of the 14ers as ‘heaps’ that didn’t really require any technical ability. Maybe Handies might fall into that.” [That comment elicited a laugh from the Hardrock 100 runners in the audience, since Handies is the Hardrock 100’s high point.]

“I’d also point out that these Colorado Mountain Club groups, with 20 to 40 people, were kind of an American tradition like a big picnic, to get out and do it. And there were so many women involved. Early American climbing was a very egalitarian sport, definitely was not the boys’ club. You’ll see women in leading roles here, writing articles about the expeditions afterwards, and basically right in the mix.”

“This is 1932 up in Ice Lakes Basin, and you can see the great camaraderie of these Colorado Mountain Club groups, especially when you read accounts of the expedition afterwards—they were so humorous, jovial, and really had a sense of unity. Everyone was having a wonderful time.

“This photo most likely was taken by William Henry Jackson, the famous Western photographer. He was the expedition photographer of the Hayden survey in 1874 and made his name during that survey. He went on to photograph all throughout the West, and he joined this group in 1932. He was 90 years old, and he rode a mule and partially hiked into Ice Lakes Basin and hung out with them for a week up there. He couldn’t do any of the climbing, but he was a mountaineer emeritus, and he enjoyed being up there and telling stories about the expeditions in the 1870s to this group.”

“This is William Henry Jackson on the left, 90 years old, hanging out at Ice Lakes Basin and coming full circle, nearly 60 years after he was up there with the Hayden Survey. He eventually died at 99 in 1941.”

“This is a first ascent of U.S. Grant Peak during that outing. You guys [the Hardrock runners] will run very close to U.S. Grant coming over Grant Swamp Pass. It has a very technical ledgy section at the top. Note the two women in berets. They were pretty proud of the U.S. Grant ascent.

“During this expedition, the group did six major first ascents in one week around Ice Lakes Basin of high 13ers. That was kind of the nature of these outings: You’d have 20 or 30 people sitting in a camp, and they’d break off into groups and start attacking peaks—everything they could see.”

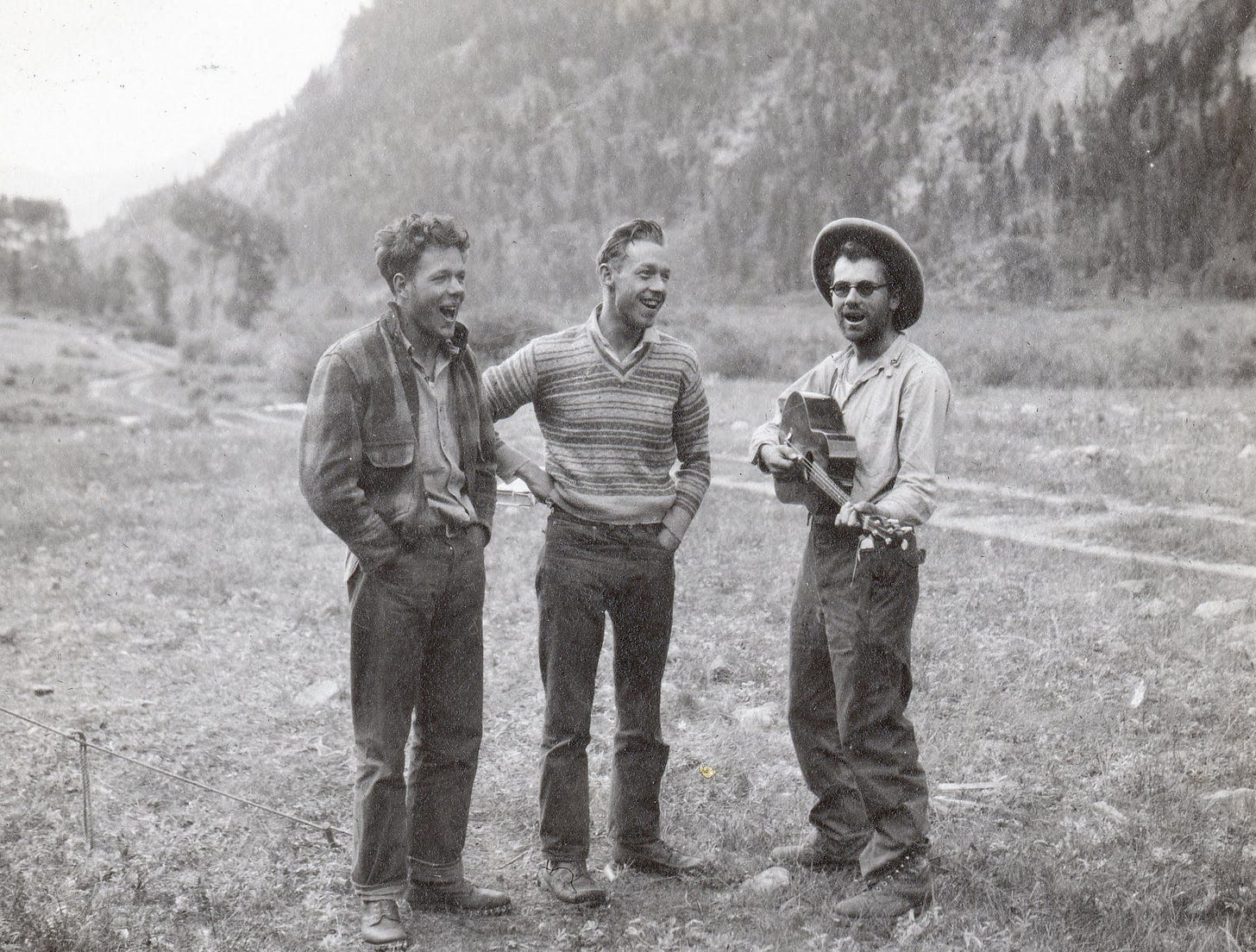

“Talk about camaraderie and humor—these guys knew how to party. They’d stay up ’til midnight and do theater performances and have huge group singalongs. That’s David Lavender on the left, I don’t know the guy in the middle, and Henry Buchtel on the right.”

“And this is the guitarist’s wife, Barbara Buchtel, in a sassy pose.”

“The San Juan Mountaineers weren’t just into climbing for recreation. Dwight realized the maps were just terrible, and they needed to improve the mapping. There had been some geologic tours since the Hayden survey, but it wasn’t good enough. So they spent three days camped out on the summit of Mount Sneffels—this is one of them, it could be Dwight—shooting different angles and triangulating, and they helped improve the elevations of these peaks and also named the peaks.”

“Here is a 1930s USGS map [printed in Dwight’s climbing guide], and Dwight has taken this map and added some of his own writing—you can see the handwritten notes [including the peaks named with a “V”]. This naming system is something he came up with. He started naming all of these unnamed peaks—there are a ton of peaks out there that weren’t named, and he had to classify them somehow to keep track of them, so he came up with a naming system that has the prefix of a letter which is the most prominent peak or town in the immediate area, so V is for Vermillion Peak, and then he would number the peaks in that group. Those are still in play—you’ve got the S group for the Sneffels group, the T group for the Telluride group, the U group for the Uncompahgre group. That is still a lasting imprint of the San Juan Mountaineers.”

[note: When I heard this, I had an “ah-ha” moment because I had always wondered why the peak I look at from my office window, next to Whipple Mountain, is named simply “S10.” How cool to know that an ancestor identified it, along with the string of other “S” peaks in the Sneffels range.]

“And this is the footwear of the day. These are hobnail boots, which have nails in them. Each one of these boots weighs almost 3 pounds. This is a far cry from your Altras and Hokas. That’s probably why these guys never could have conceived of a 100-mile running race around these mountains. These were pretty effective for mountain climbing, but certainly not for mountain running.”

“And here’s a pair of hobnails in action, or non-action. That’s Dwight Lavender.”

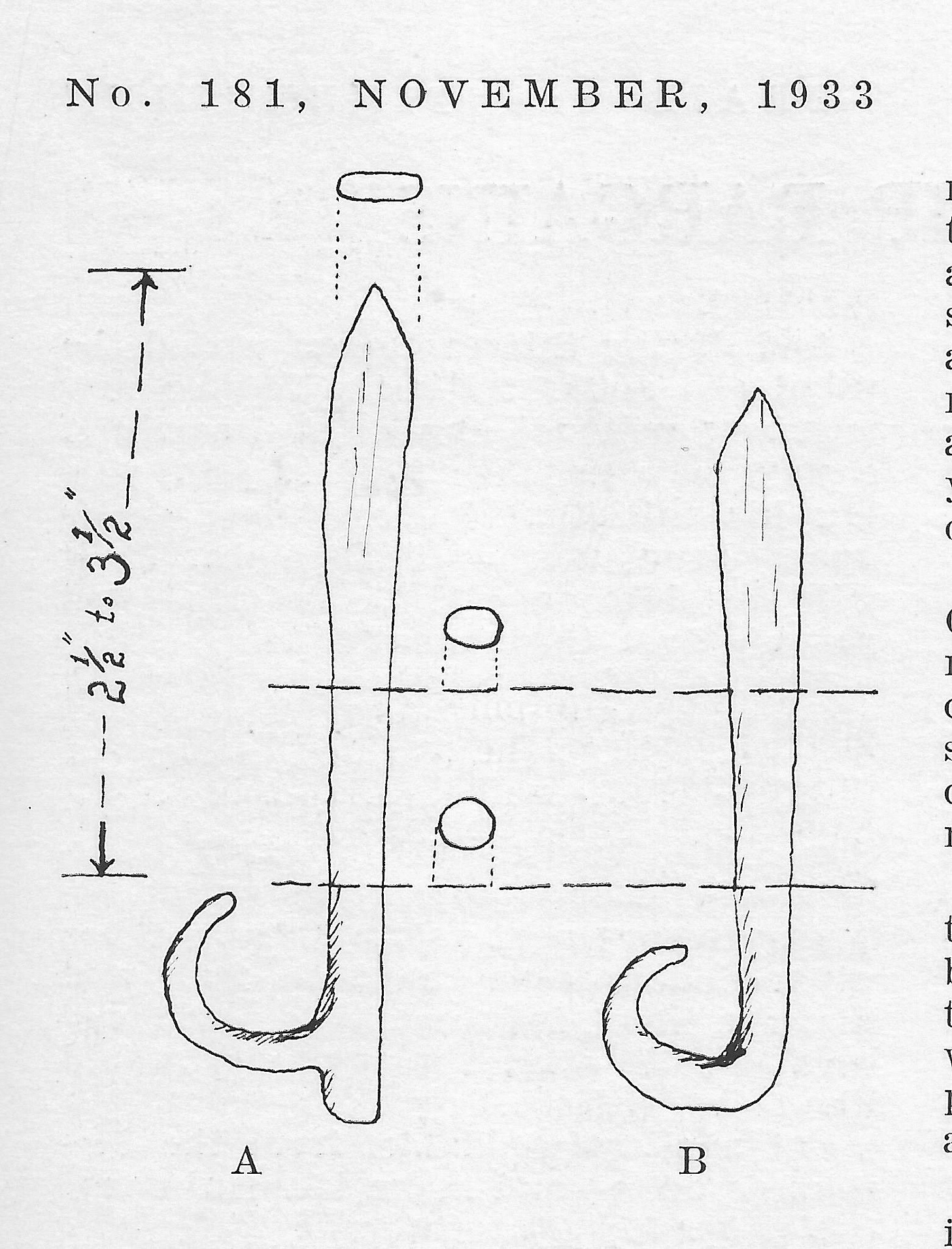

“These guys were innovators with the equipment. They were stuck down here in remote southwest CO and didn’t have access to stuff. They were figuring things out for themselves, so they started forging their own pitons out of wrought iron, which is a very malleable kind of iron. The significant thing about these pitons is the open eye; it was not welded shut here, which many pitons were. They did that so they could loop the rope into the eye of the piton. They didn’t have any carabiners. Otherwise, prior to this, they would have to place a piton, untie the rope from around their waist and thread it through the piton, retie, so a very difficult thing. The second person would have to do the same thing—untie the rope, unthread, disconnect, and clean the piton—so the open eye was very ingenious. They’d just loop the rope in there and hammer the piton flush against the rock, which would trap the rope in the eye.”

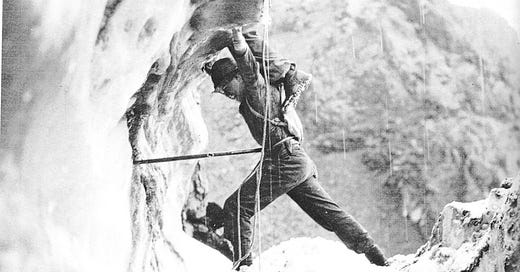

“This is certainly a picture of grit and determination, ‘wild & tough.’ This is Mel Griffiths clamping down on his pipe as he’s being subjugated by a hobnail boot in his shoulder, and you can see the guy above has a geologist’s rock hammer, which is what they’re using for piton placement.”

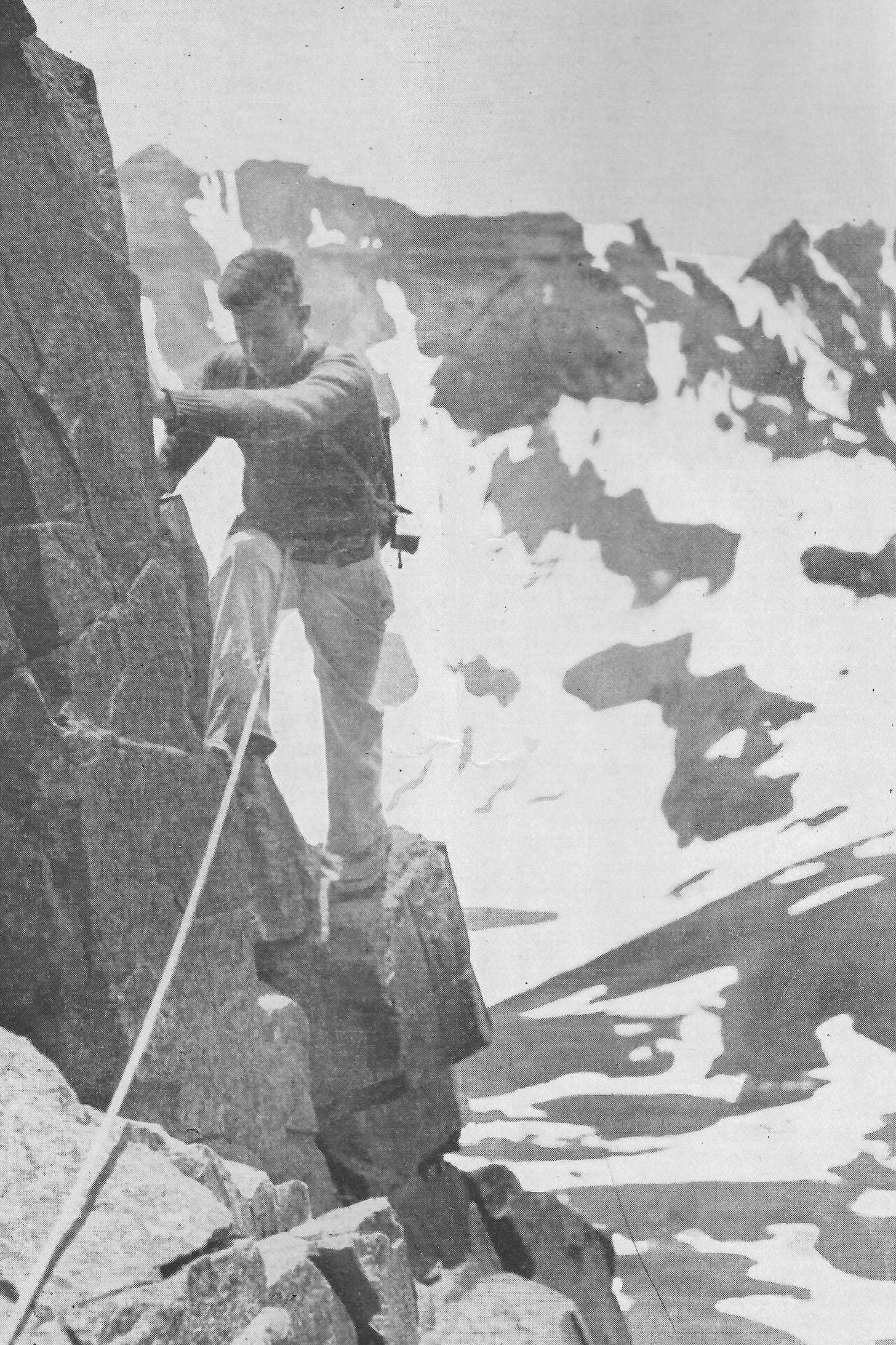

“And this is Gordon Williams on Kismet [in the Sneffels range], 1932, looking like he just came off a college campus, very preppy.”

“This is Dwight Lavender rapping off of Teakettle. Teakettle is one the high 13ers [in Sneffels range], definitely a difficult summit, fairly technical. This is called a Dulfersitz rappel [without a climbing harness or belay device], and this is how they used to rappel. They just put the rope into their crotch and up and over their shoulder, and endured the rope burns all the way down. It was not comfortable.”

“This is a great shot of Dwight Lavender here on a narrow ledge. Notice his buckskin-fringed coat. He gets major style points. He wore this thing all the time.”

“They were also pioneers in the winter mountaineering game. They were full-on ski mountaineering in the ‘30s with huge wooden skis and terrible bindings. They had to build a shelter hut below the north face of Mount Sneffels, because the approach was so long into there, especially in the wintertime, there was no way they could summit Sneffels or do anything significant in a day without having a high camp. So this was one of the first club huts or mountaineering huts in Colorado ever built. They salvaged a bunch of materials from the Blaine Mine, about 1500 meters away, and they built this little cabin here.”

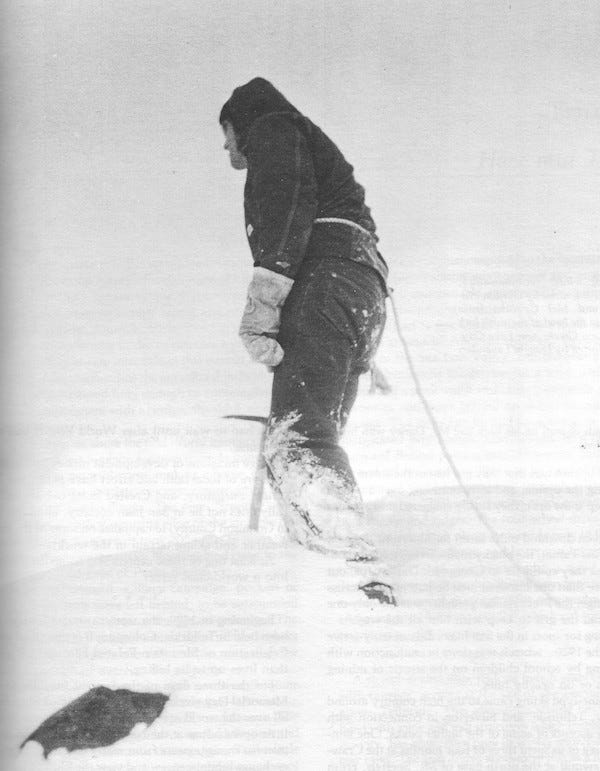

“This is Mel Griffiths on his first winter ascent of Mount Sneffels in February 1934. If you notice, he’s wearing blue jeans and a blue jean jacket. I hope he’s got some wool underwear. This is ‘wild & tough’ right there. They skied up as far as they could, then ditched the skis, climbed the peak, then skied down. He writes about this and the fantastic ski descent they had, some of the best turns he’s ever gotten.”

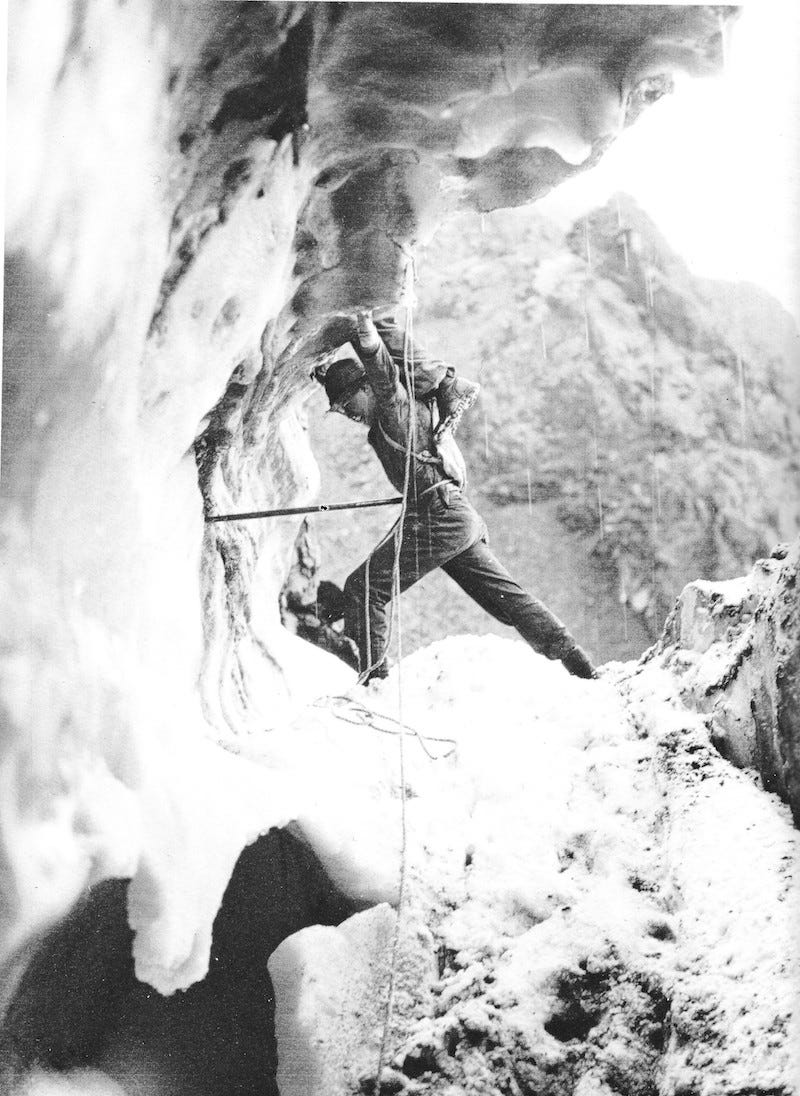

“This is a move called the short ladder, a climbing technique. Dwight is giving Lewis Giesecke a shoulder stand and popping him up over this bergschrund [a crevasse on a glacier] that’s melting out. He’s got his ice axe braced against the wall and his hip. Pretty cool technique.”

“This is one of the other pinnacles they loved to climb, called the Wolf’s Tooth on the western part of Sneffels, kind of no-man’s land out there. They wrote several accounts of climbing Wolf’s Tooth. This was a premier technical ascent where they got to place a lot of pitons. Dwight said, ‘Once again, we filled the cavities of the wolf’s tooth with pitons.’ They had great understatement. They were suffering big time—all this stuff is hard to do—but they never, ever wrote about how difficult it was. They just had some funny statements such as, ‘This was a tricky section” or, “This was ticklish.’ They were masters of understatement and used a lot of humor to get through the hard times.”

“Just last Sunday we went and climbed it again, but did not find any pitons.”

“This is a great photo by Dwight Lavender—a powerful photo for several reasons. You’ve got Cirque Mountain on the left, Teakettle, and then Potosi, and then this rock ridge on the far right is Kismet. This was such a beautiful photo—he liked it so much—he made this illustration out of it in 1931.”

“On the left the unnamed peak is now named Cirque Mountain. And Teakettle, and Coffeepot is the small mini summit in the middle there that didn’t have a name back then; Potosi, and Kismet. Another cool thing is, this location where he was is now named Lavender Col, I’m guessing because of this illustration and the photo he took, and of course because of the influence he had. Dwight was so talented with his climbing, his writing, his illustrations, photography, and his computation of the calculations for getting the summit elevations right. It’s a real tragedy he died so young.

“Mel Griffiths led the San Juan Mountaineers after Dwight died, and they continued their blitz of first ascents and flurry of activity up until the advent of World War II. That disbanded the San Juan Mountaineers because they all enlisted.”

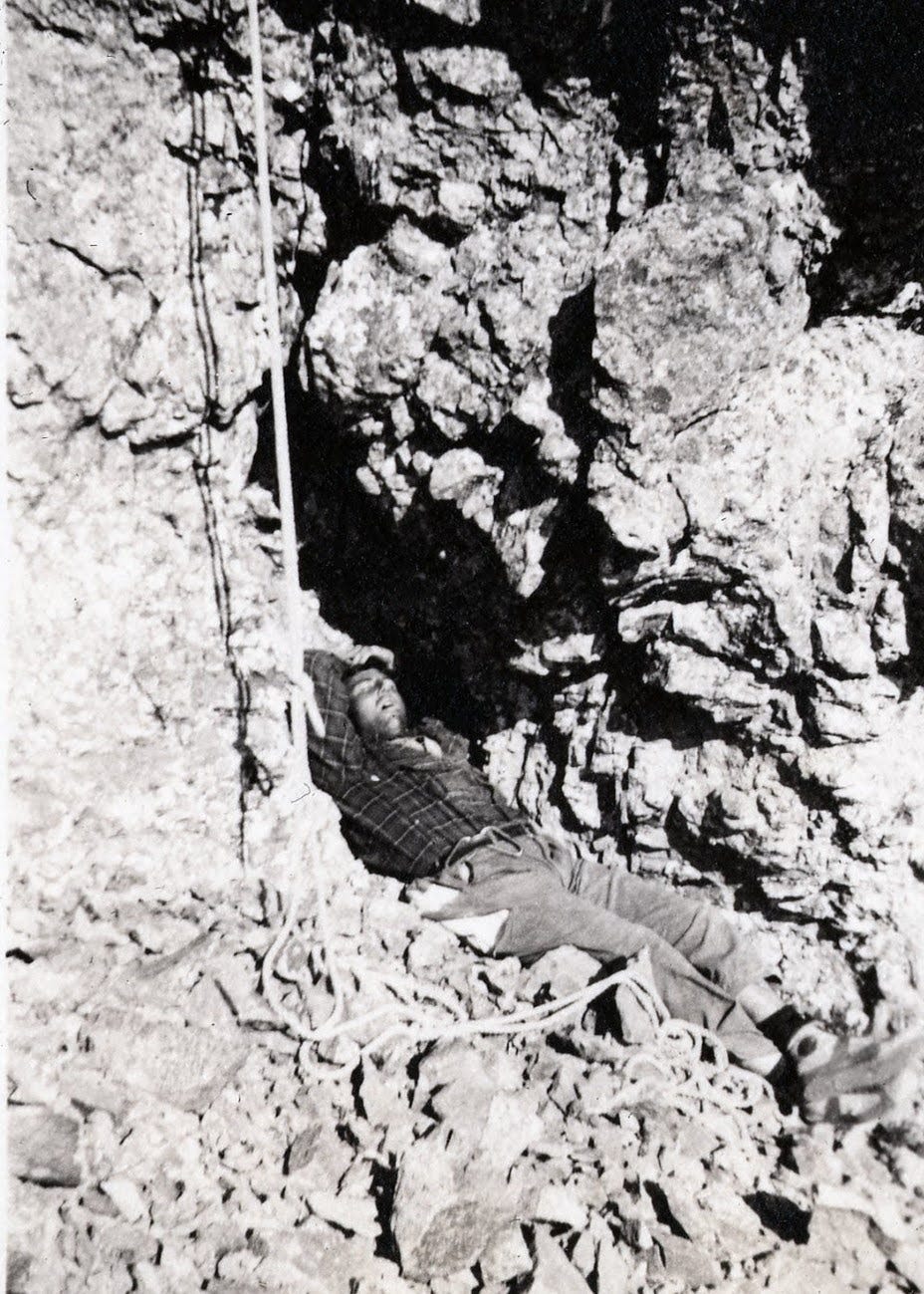

“I think this is going to be you guys after Hardrock. This is Jack Seerley [on a 1931 ascent of Lizard Head with Dwight] halfway up Lizard Head. The handwritten caption that Dwight wrote says, ‘All in!’”

Thank you so much, Pete, for putting together this fantastic narrative and collection of photos. I’ve embarked on a project to more deeply study my grandmother Brookie’s life and times, and picturing her in this context of a magical chapter in mountaineering history helps enormously and inspires me.

so fascinating!