How Hardrock's Kroger's Canteen Got Its Start

A talk with Chuck Kroger’s wife Kathy Green about early Hardrock 100 years, plus a short-but-steep race report

If you would like access to bonus content and a monthly online meetup, please consider subscribing at the supporter level. If this is your first time visiting this publication, I hope you’ll subscribe at the free or paid level to receive weekly posts.

Rundola Fundola

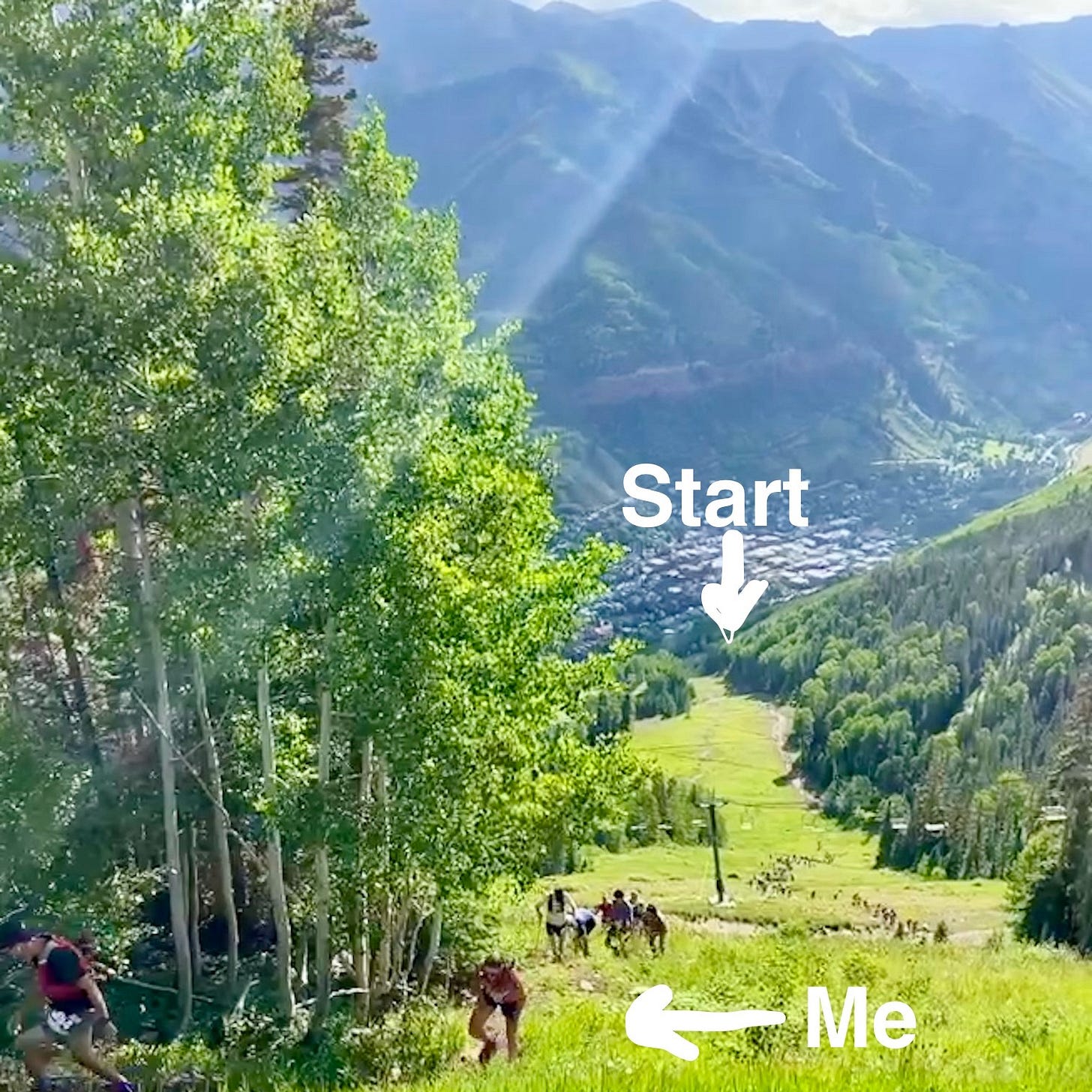

Leaning into a grassy ski slope, struggling step by step, my heart knocked against my chest and my head flirted with fainting. Others around me groaned and hyperventilated. We formed a line ascending the mountain so that we could take advantage of footholds in the dirt, as if we all were climbing the same imaginary giant ladder. I was so close to the guy in front of me—and the slope was so steep—that my head was level with his butt, and my eyes stared at his blue-striped socks.

I was about three-quarters through the short but intense hill-climb race known as the Rundola, held annually on the 4th of July in Telluride. I’ve done it almost every year since 2015. It starts at the base of the town’s gondola, elevation 8750, and goes up about 1800 feet in a mere 1.3 miles. Only the first third follows a trail, and the remainder involves scrambling up slippery grass and dirt on whatever route to the top one chooses. I barely run any of it, because I literally can’t run more than a few steps due to gravity, so I hike as hard and best as possible. At certain points, I reach and grab branches or tufts of vegetation to help scramble.

I lined up toward the front, ready to push myself to meet or beat my prior year’s time. It takes me about 35 minutes (the lead men finish in just under 23, the lead women around 28). I can hang on for that long.

All the questions and concerns that loom over ultras—such as, will my back seize up? will my knee ache? will my stomach turn? will the weather dump rain?—disappeared, because this race is too short to worry. I put my brain on autopilot, my body’s engine on high gear, and just go. Mantras crowd out thinking. This year, the chant “up up up” and the phrase “mountain legs” gave a rhythm to my steps.

The collective effort is both absurd and uplifting. Here we all are, going up this giant hill for no practical reason—the gondola gliding overhead could easily transport us, and the route was designed for skiers to go down, not hikers to go up—and yet hundreds take on the challenge. Little kids to seniors stubbornly surge and plod.

Some fun Rundola pics in this post:

The Rundola reminds me of the one time I did the Manitou Incline (2744 steps, 2020 feet of gain in slightly less than a mile), on Memorial Weekend of 2017, when I threaded my way through people of all ages and fitness levels who clogged the stairway on the holiday. Big guys who looked like they never hike on ordinary days clutched plastic gallon-sized jugs of water and dripped sweat. Getting up that giant stairway in Manitou Springs, just like getting up this ski slope in Telluride, is a challenge many find irresistible. It beckons as a dare and activates the human nature to strive and get high.

I felt stronger this year thanks to training for the San Juan Solstice 50 and High Lonesome 100. On the final pitch, when people ahead stalled to catch their breath, I stepped to their sides and took a few quicker steps to pass. I kept looking at my watch, willing myself to get up in 35 minutes.

When I got to the top and my ears filled with the shouts of my daughter and so many others yelling encouragement, I looked with amazement at the clock that read 33:10. I had managed to take off a couple of minutes.

I finished 10th woman out of more than 200 female participants, 1st in the 50 – 59 category. Ahead of me, local legend and past winner Kari Distefano, age 63, finished in 31 minutes, 5th woman. I strive to be more like her.

Memories of Chuck Kroger and Hardrock’s Early Years

Speaking of striving, I want to share the story of a legendary Telluride mountain man who left his legacy on the Hardrock 100 as well as on the trails and slopes of our box canyon.

With the Hardrock 100’s July 15 start fast approaching, I’ve plunged back into Hardrock lore. As describe in this past post, I’ve never secured a spot in Hardrock due to the long odds of the lottery. But I’ve been involved as a pacer or volunteer since 2011, and I nurture a dream to run it (hopefully in the next six years before I turn 60). This year, I will volunteer at the Animas Forks aid station, mile 58 in the clockwise route direction.

One of my favorite mini-documentaries on Hardrock is this one, from 2015, called “Kroger’s Canteen.” In it, longtime Hardrock runner and aid station captain Roch Horton describes the tiny high-altitude aid station perched on a ledge of rock at 13,100 feet at Virginius Pass, on the mountain ridge between Telluride and Ouray. A hardy team of volunteers hikes up, packs in supplies, and defies the elements to support runners. The film shows 2014 footage of champ Kilian Jornet and others ascending the scree, then pausing to get a refill of water and hot food along with high-fives from volunteers. Most also partake in a shot of tequila, or maybe it’s whiskey. Then they glissade down a headwall of snow on their way to Ouray. I encourage you to watch the seven-minute film about the Hardrock spirit and the unbelievable stories that play out on this notch in the ridge line.

This film is missing one big thing, however: an explanation of why the aid station is nicknamed “Kroger’s Canteen.” Let me tell you about the namesake, Chuck Kroger, and what his Virginius Pass aid station and the Telluride aid station were like in Hardrock’s first year, 1992.

I know these details from getting to know Chuck Kroger’s wife, Kathy Green. I connected with her through a book club via Zoom during the pandemic. She periodically would make astute comments about ultrarunning when the topic came up, which left me wondering, why does this older artist care about running, and how does she seem to know so much about Hardrock? Finally, someone clued me in: Kathy Green was married to Chuck Kroger until he died in 2007. Which means Kathy, along with Chuck, was involved with Hardrock since the beginning.

A very brief history on Chuck Kroger for context: Born in 1946, Chuck was a standout climber in the 1960s, traveling from Yosemite to the Alps, Soviet Union, and South America to make extreme and record-setting ascents (e.g., the first person to climb four routes on El Capitan in a single season). In 1975, during a Grand Canyon trip, he met his future wife Kathy, who was working as a park ranger. They bonded over books (especially On the Loose by Terry and Renny Russell and The Monkey Wrench Gang by Edward Abbey) and fell in love. The couple arrived in Telluride in 1979, just as the town was transitioning into a ski resort. As craftpeople as well as outdoor enthusiasts, they started BONE (Back Of Nowhere Engineering) Construction to build houses and employ locals.

A little over a year in Telluride, however, Chuck noticed something wrong with his health. A lump in his abdomen, which he thought was a hernia, turned out to be non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. After radiation and other cancer treatments in 1981, Chuck took up running to help regain health.

“What he really loved about running is you could just go by yourself, anytime, anywhere,” Kathy told me. All you needed were shoes, unlike gear-intensive climbing. “At first he was focused on road races, and there was only Imogene as a trail race. But then as there got to be more trail runs around here, like Kendall and Get High, he started doing more of those.”

Additionally, during cancer treatment, he worked on raising his house and creating a basement to make a workshop, Kathy recalls. Much of it had to be hand excavated because heavy equipment couldn’t access the space, so he’d dig and shovel 10 wheelbarrows a day.

“His way to get well from cancer—and get a workshop—was to hand dig our basement by himself. He was big on endurance.”

Fast forward a decade, and three mountain runners he had gotten to know—John Cappis, Charlie Thorn, and Gordon Hardman—told Chuck they were developing a 100-mile race linking Silverton, Ouray, Telluride, and skirting Lake City. “They said, we want to have this place up on Virginius Pass, but it’s going to be too steep, and we need you to go up there and put a rope on it. And so, Chuck is like, ‘OK.’”

Not only did Chuck go up there to affix a rope to help runners descend the snowy north-facing side (in Hardrock’s first year, the route went clockwise and began the tradition of switching direction each year). He also manned the first-ever aid station up there by himself. Meanwhile, Kathy single-handedly worked the Telluride aid station, which that first year was in town at Elks Park rather than its current location of Town Park.

How did that first year go? Put simply, many of the runners had no idea what they faced when they took off from Silverton toward Telluride. Of the 42 starters, 18 finished.

Kathy was alone at her Telluride aid station, Mile 24 on the route, in the afternoon, waiting for the final runners to come through before the 5 p.m. cutoff. Eventually, seven stragglers arrived. The first-year results show they all came from West Coast states and Hawaii.

“They’ve come down Bear Creek, and they’ve lost their shoes post-holing—they got them back, but the shoes would come off and they’d have to stop and put them back on—and it’s almost the cutoff time, and they’re talking about how cold they are, and I’m thinking, they’ve only done a quarter of the course and there’s worse snow ahead, because it was a bigger snow year.”

She said some of the runners had done extra-long ultras before, such as the Sri Chinmoy six-day, “so they could run an incredible distance nonstop for days, but they’d never been in snow before. … So I’m like, ‘Do you want to drop out of the race?’ and they’re like, ‘OK,’ so I say, ‘I’ll take you all up to my house and feed you.’ And I have no way to talk to anybody in Silverton” because no cell service existed in town in those days.

“So I take all these people to my house, and get out all the soup I have and pour it together in one pot, and get out crackers, and I take all their wet clothes and put them in my dryer and give them jackets. Then I start trying to call to somebody in Silverton—I start calling to restaurants there and finally get somebody on the phone, and I say, ‘I have six or seven of your runners and you need to send a van to come get them, because they’re out of the race and want to come back.’ Eventually a van appears and takes them away, and right after that, Chuck calls me [he had a borrowed satellite phone for Virginius Pass] and says, ‘the last runner from Telluride has now cleared. But I have one guy who dropped out, so he’s going to walk down with me, and he’ll spend the night with us.’ So they showed up much later in the dark. We put him in our guest room and fed him breakfast, and the next morning Silverton had to send a van again.

“I never ran the Telluride aid station again—they probably didn’t want me to, because I pulled so many people out of the race. But nobody understood the course then. People didn’t understand these extreme mountain runs. So that’s our experience with year one.”

In the next few years, Kathy, then in her mid-40s, helped Chuck run the Virginius Pass aid station (the event was cancelled in 1995 due to snowpack). The aid station earned the nickname Kroger’s Canteen, and the team expanded to about five people, including a ham radio operator. Chuck, Kathy, and their helpers would drive up the rugged Tomboy Road, gain access through a locked gate to drive partway up Marshall Basin, and then hike up the mountainside to Virginius carrying cookstoves, big pots, sleeping bags, tarps, and other gear.

They did not, however, lug water. Instead, they melted copious amounts of snow to provide water to runners.

“I just remember trying to melt snow and having boiling pots of water to make coffee and soup,” Kathy said. “I liked being up there, but when it’s thundering and lightning, because you’re so exposed, that’s scary. I did think some of the Hardrock runners were a little crazy.”

In 1997, at age 50, Chuck decided to try the run himself. He made it to Mile 59. That year, and in 1998, he dropped. Kathy attributes the DNFs partly to lack of training, but also, he had an intestinal blockage from his cancer treatments in the 1980s that hampered his physiology. Surgery in 1999 repaired it, which helped him finish for the first time in 2000 at age 54 in just under 44 hours.

Chuck went on to run Hardrock six times, through 2006, with a personal best of 42:13 (in 2001) and slowest time of 47:36 (2003). Kathy always served as his crew person, sustaining long nights around Ouray and Silverton in pouring rain.

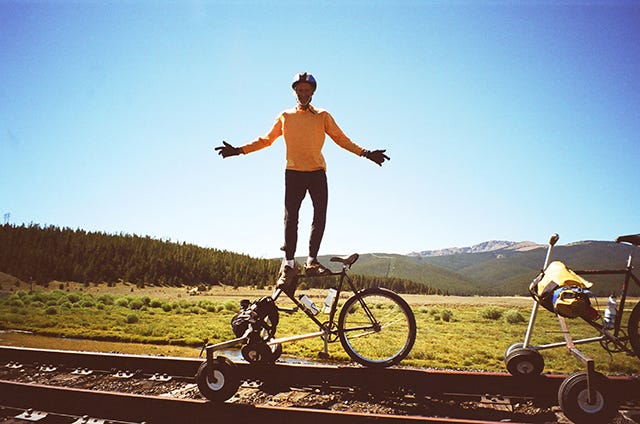

During these years, when not running, Chuck developed skills as a tinkerer and welder. He converted bikes to fit onto abandoned railway lines and would take friends cruising on the tracks, and he also fitted bike tires with studs to ride down the frozen Dolores River in winter.

A devoted trail builder, he made and improved routes around Telluride and used his welding skills to make trail signs that still mark many trails. Hardrock runners on the summit between Telluride and Ophir can see an example of his handcrafted metal signs at the McCarron Junction.

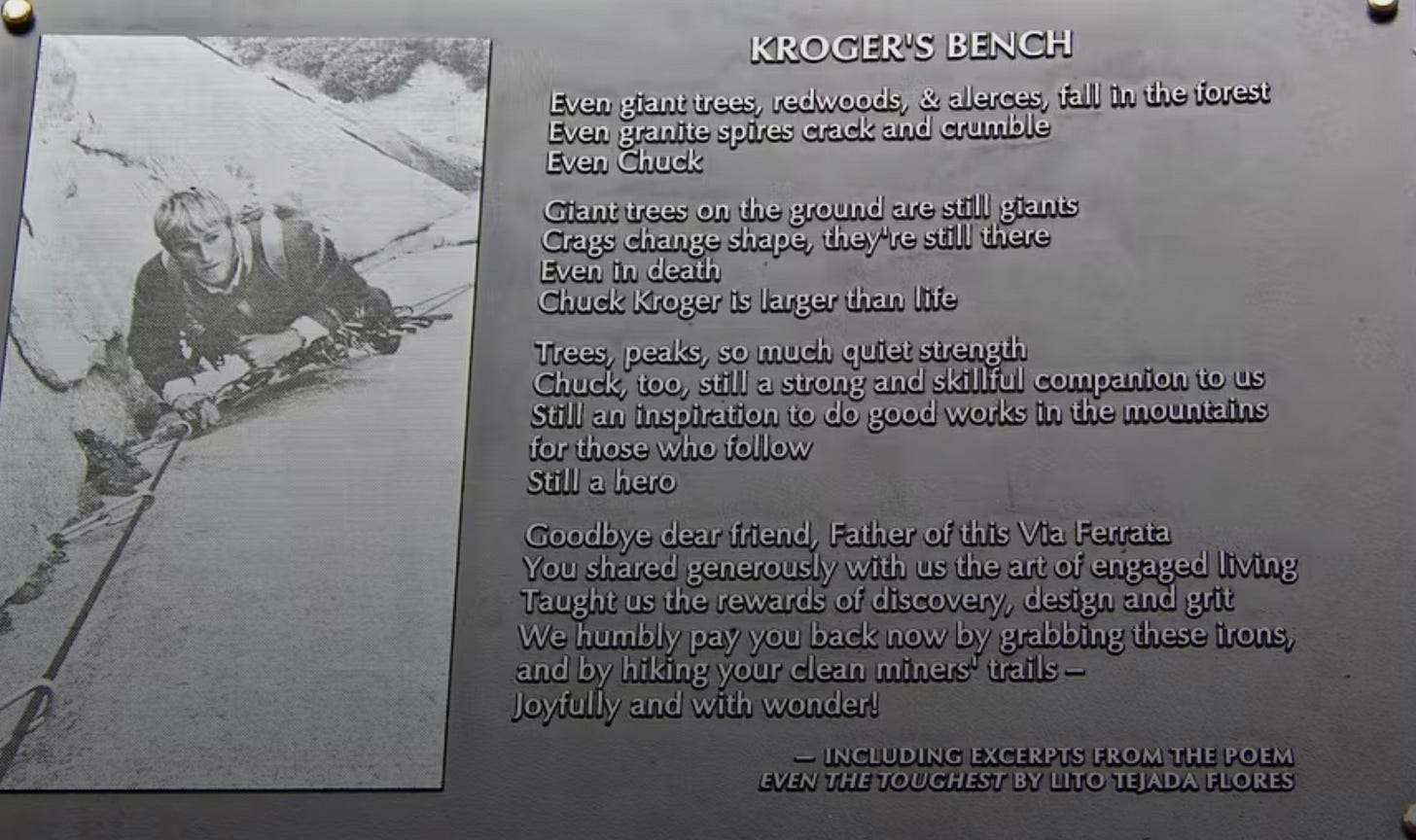

But Chuck Kroger’s biggest gift to Telluride is the town’s via ferrata. Along the vertical box canyon wall to the north of Ingram Falls (on the left if you’re looking at the waterfall at the end of Telluride), Chuck combined his ironworking and climbing skills to create a horizontal traverse of iron hand and foot holds modeled after via ferrata routes he had seen in the Dolomites.

It was not sanctioned or permitted, and the Forest Service and other powers-that-be probably would’ve had a cow about it. Think of the liability! He just did it, with Kathy’s help. Starting in 2006, the couple created metal holds in their basement, and then Chuck bolted them to the rock face.

Word started to get out about the secret route, nicknamed the Krogerata, and 15 years later, it’s one of the most popular attractions in Telluride and managed by the Telluride Mountain Club, with hundreds of people traversing it each summer.

The first phase of the Via Ferrata was barely finished in 2007 when Chuck became ill. Kathy said he noticed on a river trip in March of that year that he could not row as powerfully as he thought he should. Then, at the 2007 Hardrock at age 61, “he was just really slow getting to Sherman [Aid Station]— it was a counterclockwise year—and I got a message that he’s dropping. We came back to Telluride and had a little party, and he was finishing the via ferrata—it was basically done and usable—so they all went up and did the via ferrata instead.”

A week or two later, Kathy said, he got out of the shower and told her he was strangely yellow. The jaundice was a sign of his organs beginning to fail.

Two weeks after Hardrock, he got a diagnosis of Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. He lived for five more months and died on Christmas Day.

Kathy, of course, still loves and misses Chuck, and consequently, the annual Hardrock tradition is bittersweet. “I haven’t been to the finish line or awards ceremony since 2006. That would make me cry,” she said. But she enjoys seeing Hardrockers go past her house above Telluride as they make their way along Willow Street and Gregory Avenue, the roads that connect the trail route to Town Park.

Hardrock old-timers and locals who know of her connection to the event have returned stray Hardrock trail markers to her home. “It used to be that everybody who went hiking and found markers would stick them in my garden,” she said. “Sometimes I still find markers in my yard.”

I am so grateful to Kathy for sharing her memories and enhancing my appreciation for Chuck Kroger, and for all the men and women who had a hand in starting the Hardrock 100. Her example of working aid stations has fired me up to work hard as a volunteer next week.

For more on Chuck and Kathy, check out these two excellent articles in Telluride Magazine and Adventure Journal. For more on this year’s race, read iRunFar’s preview.

If you’re in the Silverton area on Tuesday, July 12, at 6 p.m., I hope you’ll come to a talk I’m giving at the school’s Performing Arts Center about mining and mountaineering history in the San Juan Mountains.

Thank you for sharing the story of Kroger's, what a fascinating life lived!

As far as your Rundola - along with my and hundreds of local's obsession with Manitou Inlcine - yes, it is strangely addictive. Today was my #95 (I think) in 3 years, last year being the "worst" with weekly trips.

Chuck was the best! And Kathy is so sweet! I miss them both, I’ll have to reach out her next time I’m in the area.

I have a short story about Chuck. We were running John Cappis’ Get Over It (his version of Get High) and Chuck and I ended up running most of the 2nd half together. It was great to hear his stories, especially about the rail bike! At some point he tripped on something and fell head first into jagged rocks. It was a superficial cut but it bled a lot. He was fine but I think he was concerned Kathy would be really worried about him because of all the blood. There he is out in the middle of nowhere, bleeding like crazy, but worried about his wife. Such sweet folks.