Digging Into the San Juan Mountains

Stories from history of exploration and development around the Hardrock 100 course, with a personal twist

Welcome back, and apologies this post comes to you a day late. I spent part of this week in Silverton, and will return there very early tomorrow morning to volunteer for 24+ hours at a Hardrock 100 aid station above 11,000 feet, where the monsoon storms promise to make the experience wet and wild for runners, crew, and us volunteers. My goal 100-miler, High Lonesome, takes place a week from tomorrow (gulp), and I have fallen behind on writing and other projects in order to make time for Hardrock volunteering and High Lonesome running.

This area is abuzz with excitement about Hardrock, the iconic 100-miler that starts Friday, 30 years after its much quieter start in 1992 (though this is not the 30th running, due to a few years’ cancelations. It’s the 27th, if I counted correctly). If you want to follow Hardrock and learn about this year’s competitors, check out iRunFar’s coverage and read my past post about what makes the race special and how the lottery works.

Even though I have not yet had the luck of the lottery draw to run this event, I love the vibe in and around Silverton the preceding week. For example, I ran into filmmaker Billy Yang last weekend while he was on top of Grant Swamp Pass; he’s in town to pace a friend in the race. Reconnecting with friends like him, who come from all over the country, makes Hardrock feel like a reunion and festival even for those of us not running it.

Take a close look at that photo of Island Lake and the surrounding mountains, as it ties into the story I relate at the end of this post about my grandmother’s experience there 90 years ago!

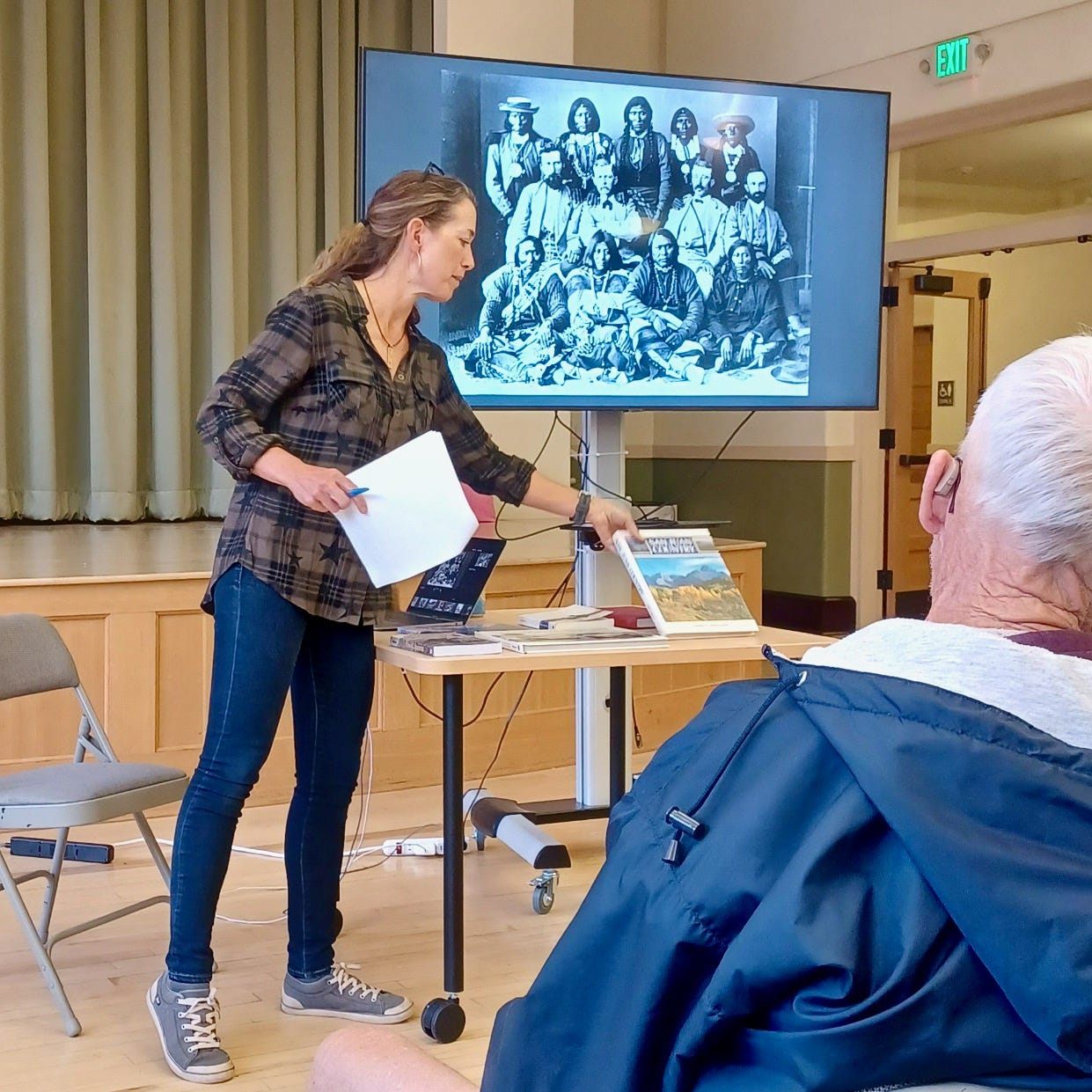

Hardrock Race Director Dale Garland invited me to give a talk on regional history to Hardrock participants on Tuesday night, and I’ve reproduced my remarks below. Not wanting to make this presentation solo, I asked if Pete Davis could speak too because his research on the original San Juan Mountaineers is so interesting. Pete has been researching my grandfather’s brother—my great-uncle Dwight Lavender—who was a founding member of the San Juan Mountaineers. Pete’s presentation on the skills, spirit, and legacy of these pioneering climbers and explorers was so special, I will save it for its own followup post.

Meanwhile, I hope the stories below on surveyors, prospectors, and miners enlighten your appreciation for the trails and towns along the Hardrock 100 route. This is an extra-long post, so thank you for reading!

Disclaimer: I am not an expert in regional history. But I’ve done a fair amount of reading about it, and I also have stories passed down from family about these mountains, starting in the 1880s, because my family roots are here.

And like you, I have a fascination with the mining remnants we come across when running and hiking these trails—especially the giant chunks of rusted equipment and the collapsing structures. My imagination tries to picture the people who worked and lived here a century ago. How did they do what they did in such harsh conditions?

I begin with this photo from 1897 of Telluride’s main street because it shows one primary way the mine operators transported materials to the mines. These 52 mules were strung together to carry 10,000 feet of cable up to the Nellie Mine to build an aerial tramway. You’ll come across Nellie remnants when you run down the Wasatch Basin [around mile 20 in Hardrock’s clockwise direction] right before crossing the little wooden bridge. We all know how narrow that trail is. Can you imagine if any one of these mules had slipped and fallen down the canyon into Bear Creek, since they’re all hooked together? I share this as just one example of the intrepidness and hard work—both human and equine—used to develop the area’s mines.

What Pete Davis and I hope to do tonight is inspire you with examples of “wild & tough” [that’s the Hardrock 100 motto] explorers and climbers from a century ago. I hope in this way to make your Hardrock run not just a test of endurance and competition, but also a historical tour, so that when you’re going over the Mendota saddle on your way to Kroger’s Canteen, and you look down at those three basins so rich in history—the Liberty, Marshall, and Savage basins above Telluride—or when you’re running down Camp Bird Road on your way to Ouray, and on so many spots on the route when you see historic artifacts, I hope you feel some connection to the courageous people who explored, worked, and suffered on these mountainsides.

If you keep in mind the challenges and hardships that took place on these trails from over a century ago, then maybe it’ll give you perspective to make your run feel a bit more manageable.

We’re also talking to you tonight because history is integral to the Hardrock 100. Charlie Thorn, who designed the course with John Cappis and Gordon Hardman for the first run in 1992, said they wanted to “create a 100-mile run that would keep in mind—keep the memory—of the old mining days alive.” (I got that Charlie Thorn quote from an excellent piece that Meghan Hicks wrote in 2016 called “Sharing the Lode.” I recommend her article for an overview of all the mines and a lot of the history along the Hardrock route.)

What I want to share with you is not a comprehensive history but rather, some stories and descriptions of three types of non-native men who explored, worked, and adventured here in this part of the San Juan Mountains, starting in the 1870s through the early 1900s.

These three men are: the surveyors, the prospectors, and the miners.

I’ll start by telling you a bit about my ancestors as a way to show what some of the characters and politics around here were like in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. My great-great grandfather Charles Painter came to Telluride from Ohio around 1880 when he was a young man in his 20s, and he was part of a population rush to the region starting in the mid 1870s. He was not a miner or mountain man, however; he was looking for entrepreneurial opportunities in the new towns. He was appointed clerk of the newly formed San Miguel County, was elected Telluride’s first mayor in 1882, and published the town’s first newspaper. He also started a title business, which my grandfather wrote was “a necessary calling in a land where mining claims overlapped like a deck of messed-up cards.”

Charles Painter built a house in downtown Telluride, at the corner of Fir and Columbia, in the architectural style known as Bonanza Victorian. This is where my grandfather David and his brother Dwight were born in 1910 and 1911. What’s interesting historically about their home birth is a new hospital stood two blocks up the street—the beautiful stone building that now houses the Telluride Museum. Why give birth at home instead of at the new hospital? Because that hospital was built for the miner’s union, and my great-great grandfather did not want his son and daughter-in-law to patronize the miner’s union hospital. Labor tensions in town remained extremely raw in 1910 following labor strikes and the assassination of the superintendent of the Smuggler-Union mine.

This region saw intense labor strife and strikes between 1901-1903. The Western Federation of Miners was organizing workers to fight for an 8-hour day and safer working conditions, and they were trying to block non-unionized workers from breaking their strike. In 1903, gun battles broke out between unionized workers and so-called scabs. I bring this up partly because some of you may have run up to Fort Peabody above Imogene Pass, which is on the Ouray 100 course as one of the peaks that gets tagged in that race. I encourage you to take a little detour up the mountain to see it if ever you’re running over Imogene.

This fort was built at the end of 1903 because the mine owners and managers, who were trying to break the strike, would forcibly deport unionized workers and their sympathizers out of town. Then the union activists would try to return to Telluride on foot over Imogene Pass. The National Guard built this post above 13,000 feet, named after then-Governor James Peabody, and guards would prevent any union workers from crossing between Telluride and Ouray. I find it hard to believe how tense and violent this now-peaceful and beautiful setting was 119 years ago. It’s mind-boggling to me that up on that summit, armed guards camped out to confront activists trying to hike past at nighttime to get back to their families on the other side of the mountain.

I must admit, my great-great grandfather stoked that violence. Charles Painter was a leader in forming a Citizens Alliance to support mine owners, and in 1903 he supervised the passing out of rifles to these citizens to create a militia to fight the unions.

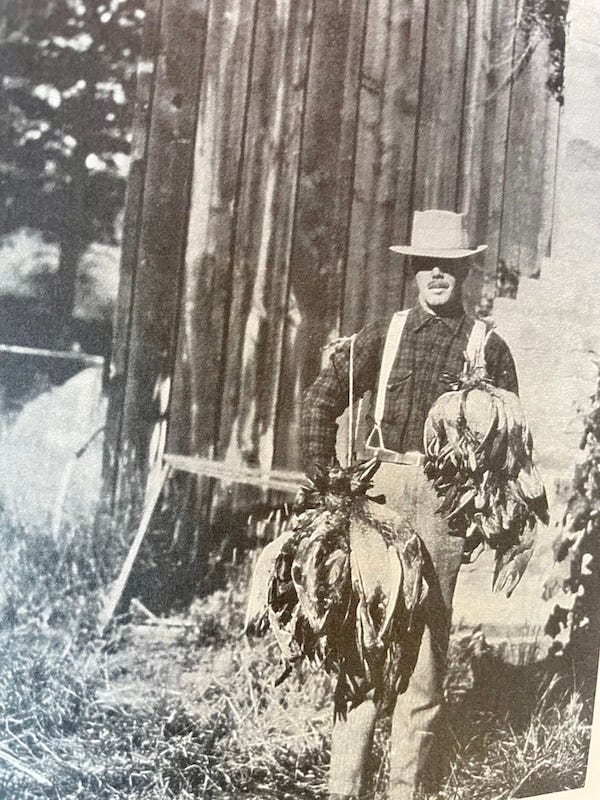

So my grandfather and great-uncle were born into that context of political and class tension, because of their grandfather and father’s leadership in town. Early on, however, their privileged lives changed dramatically due to family tension, and they gained a very different father figure as a mentor who influenced them to become rugged mountain workers and athletes. In 1921, their mother divorced and remarried a man named Ed Lavender, who adopted my grandfather and his brother, changing our family’s last name from Painter to Lavender. This is one of the rare family photos of Ed, from the mid 1920s, holding a bunch of grouse he shot.

Ed Lavender was typical of entrepreneurial mountain men in this region in the early 1900s. He worked as a freight operator, which means he transported goods from town to the mines by mule and wagon, and he also had a blacksmith shop in Telluride. He grew alfalfa on Deep Creek Mesa, where I now live, to feed the livestock in town. When aerial tramways largely replaced the need for mules, Ed started buying up large swaths of land around Telluride and the west end of San Miguel County for cattle ranching, and at one point in the 1920s and early ‘30s, he owned and managed the largest cattle operation in southwest Colorado, the Club Ranch.

Because of their stepfather, both my grandfather and great-uncle spent their summers off from school working as ranch hands and cowboys to move cattle while spending their free time exploring and climbing the San Juan Mountains.

So that’s the family history in a nutshell that gives me a personal interest in this region’s history. Let’s back up now to that era when my great-great grandfather arrived here. The 1870s and ‘80s were boom times for the towns around the Hardrock course, and I’ll highlight the mountain explorers who opened up the region for that population growth.

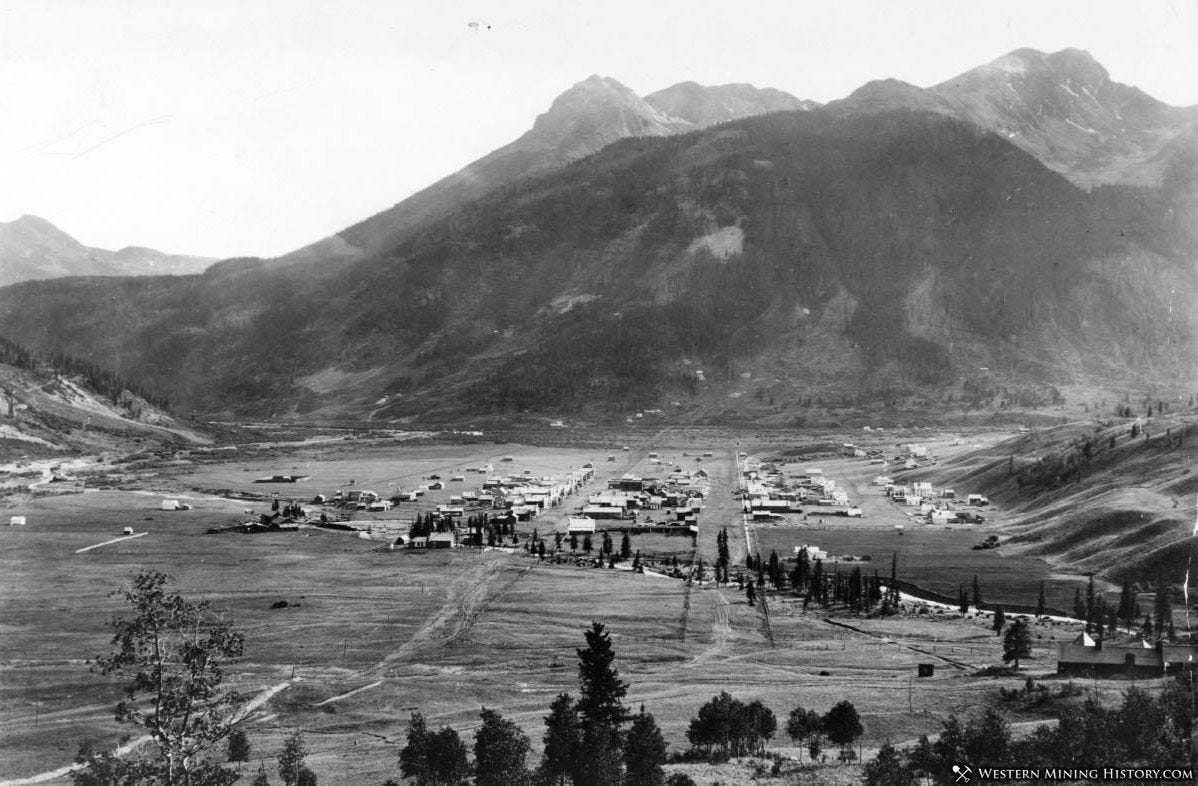

It amazes me to think that Silverton, pictured here in 1878, was established first as a small settlement camp called Baker’s Park in 1860, and just two decades later, its population was around 5000—compared to about 600 full-time residents now—and it was the third largest city in the state behind Denver and Leadville. How did that happen?

Gold was first discovered in Colorado in 1858 in the northeast part of the state. Charles Baker and his party found some placer deposits of gold here around 1860, but their settlement petered out after only a couple of years. They left because they were in conflict with the Ute tribes and were drawn back East to the Civil War.

The first big lode strike that drew scores, perhaps hundreds, of people here to Silverton happened in 1870, when a prospector named Miles T. Johnson found the Little Giant vein in Arrastra Gulch, just 3.5 miles east of here, and started the Little Giant Mine.

Let me explain briefly in simple terms the difference between lode and placer mining: Lode refers to lode deposit, which is mineral encased in rock. These minerals were injected into the rock by volcanic eruptions tens of millions of years ago, and the magma filled crevices with mineral deposits that branch out in veins. The hardrock miners around here worked the rock to extract the lode from these veins.

Then there’s placer, which are deposits containing valuable minerals that come from fragments of lode that disintegrated from the rock through weathering and erosion, and the placer deposits got transported by water. Most of the gold in the California gold rush came from placer in stream beds.

There was a big problem with this first hardrock mine operation that started here in 1870: All of the workers and settlers were trespassing on Ute land. A treaty between the Utes and U.S. government in 1868 had given the Ute bands the western third of Colorado as a reservation in exchange for the Utes ceding the Central Rockies to the United States. But two years after that agreement, the government began to realize the valuable minerals here in the San Juan Mountains and began renegotiating that earlier treaty.

Chief Ouray, the main negotiator for the Utes, was a peace-keeper who did his best to discourage his tribes from attacking prospectors in the area. He struck a deal in 1873, called the Brunot Agreement, to give 3.7 million acres, or about 5800 square miles, of these San Juan Mountains to the United States in exchange for the government making annual payments of $25,000 to the tribe.

Because of this agreement, starting in 1874, prospectors could travel freely around Silverton and Ouray, and in 1874, Baker’s Park settlement became the town of Silverton. The town of Telluride was founded four years later, originally under the name Columbia.

“News of the 1873 treaty touched off a rush of prospectors to the San Juans in 1874,” wrote Mel Griffiths in his excellent 1984 book San Juan Country. (Mel was one of the original San Juan Mountaineers.) “The clandestine mining which had gone on around Silverton in the early 1870s had seldom engaged more than 40 to 50 miners per season. By 1880, it is estimated that no less than 7000 mines and prospects had been located and recorded in the several mining districts of the San Juans. Only a small percentage of these were productive, but they represented the unbounded hopes of their discoverers.”

This first generation of men who worked these mountains did it for two main reasons: science and money. It was hard work driven by the concept of Manifest Destiny and the desire to strike it rich, or at least to eke out a living.

The Surveyors

The first mountain worker and explorer I want to highlight are the surveyors, the most famous of whom was Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden.

Between 1867 and 1879, four major expeditions, sponsored by the US government, explored, surveyed, and mapped areas west of the Mississippi. These were known as the Great Surveys of the American West, and Hayden’s survey was the most important for gathering knowledge about the geography and geology of Colorado.

According to the guidebook The Peaks of Telluride, “There is much written about Hayden as a man full of energy and drive. He was said to have pushed himself and his men unmercifully. One name for him by the Indians was ‘he who picks up stones while running.’ He was called ‘Little Man Alone’ by the Utes because he seemed to always be by himself sketching, studying and taking samples.”

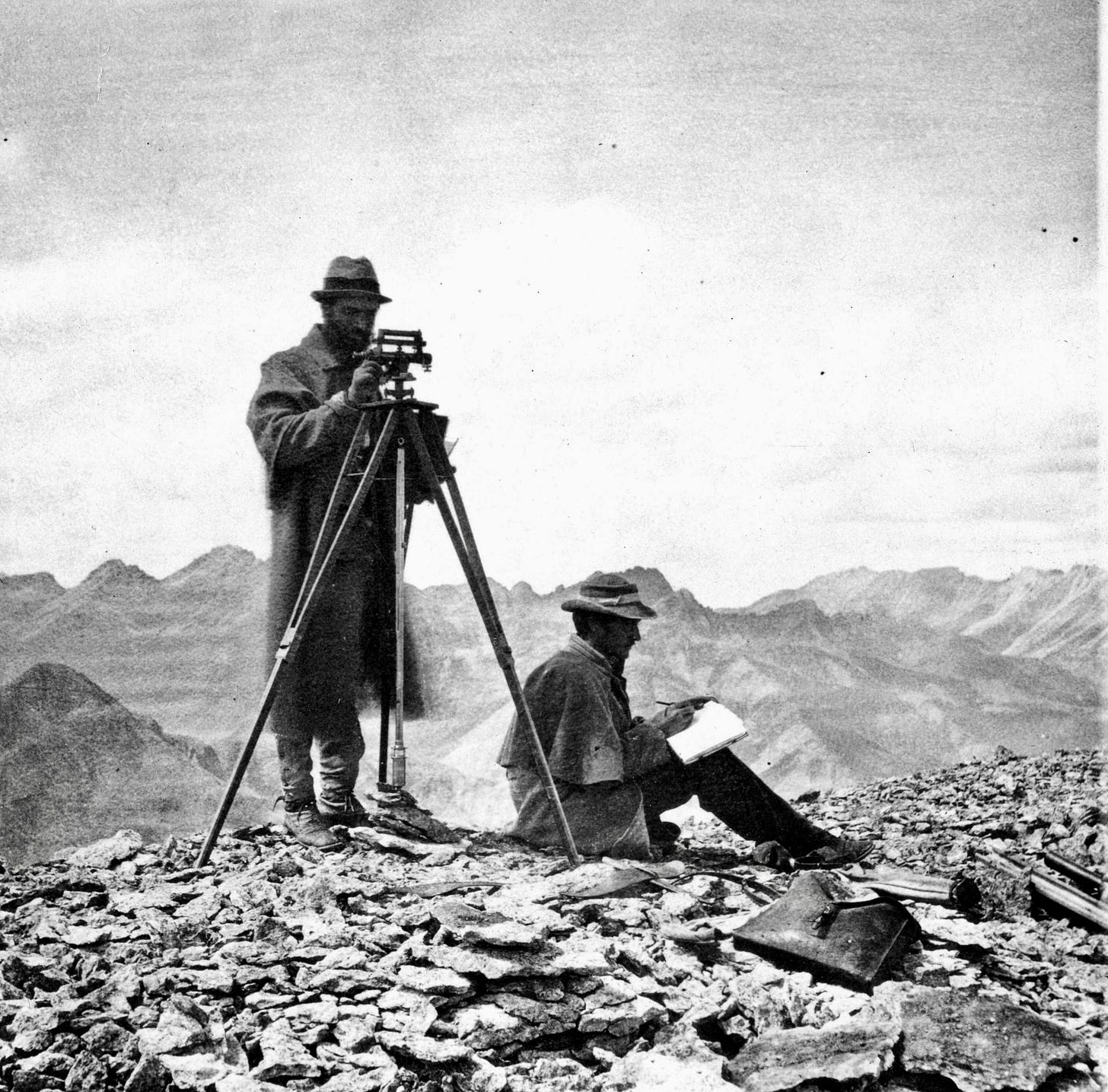

One of the most impressive things, I think, is how these groups ascended numerous 14’ers, with no known routes and while carrying all their scientific equipment, to map and study the area. They had to reach peaks to triangulate height and location, so these men developed mountaineering skills by necessity. Their equipment included tripods, sketch books, a barometer, and a theodolite to measure angles. They often did this through intense storms. Their maps and reports contributed hugely to the development and railroad building in the region.

The Prospectors

Now we get to mining, and the first step in the mining process is the prospector. As described in Mel Griffiths’ book: “The stereotype of the western prospector depicts him with his faithful burro packed with shovel, pick, and gold pan; bed roll, beans and flour. … He roams the hill country looking for promising leads. When he finds the likely lode or placer deposit, he stakes his claim and records it with the proper authorities. This procedure gives him a proprietary ownership in his discovery.”

I want to tell you about a man from 1875 who hopefully will inspire you as you make your way from the Mendota saddle to Virginius Pass. As you go up the Liberty Bell Basin and then over Mendota, you’ll look down on Marshall Basin, where the Smuggler-Union and Sheridan mines operated, and beyond that, you can glimpse Savage Basin at the base of Imogene Pass where the Tomboy Mine operated. These were fabulously successful mines, and full communities sprung up around them in the mid-1880s; at one point, some 2000 people lived in and around Tomboy Mine, and the settlement included a school and even a YMCA and tennis court. I highly recommend the memoir Tomboy Bride by Harriet Fish Backus about what it was like to live and raise a baby there in the early 1900s.

These mines got their start because in late July or early August of 1875, a man named John Fallon was brave enough to go over the ridge from Ouray to that basin, and he went through a notch in the ridge that likely was Virginius Pass.

Imagine what it would be like, if you’re going in the counterclockwise direction of the Hardrock route, to go up that steep slope to Virginius, while leading a string of burros, then reach the ridge and have to make your way down with no trail and no sign of anyone else having been there.

It's unclear whether John Fallon was alone or had a partner or two with him. In any case, he followed the mineral markings of a vein that led him toward Mendota Peak. He used his feet to measure out five claims in Marshall Basin, each claim being about 1500 feet long and 300 feet wide, or close to 10 acres, and he named and took notes on the locations of these claims. The law required that he sink a discovery shaft into each claim and bring back ore from it. So he did that, and took back samples of his ore on the burros’ backs. Legend has it that when he made his way back to Silverton, he received $10,000 for the gold contained in that ore. [Note: much of this information comes from my grandfather’s book The Telluride Story, which I also recommend.]

That started the rush of other prospectors and miners to the basins above Telluride.

The Miners

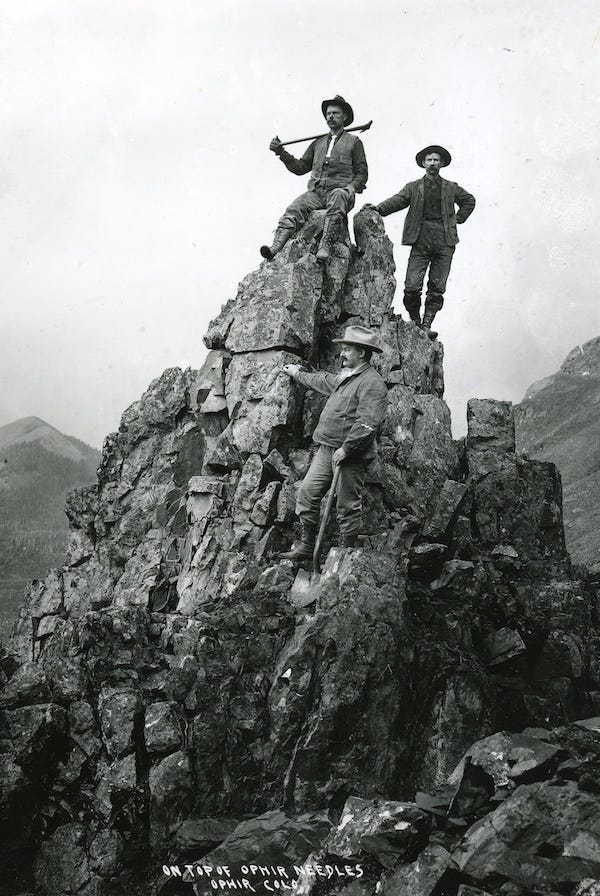

Now let’s look at the miners’ job. This is a photo of miners posing above Ophir, and given their mountaineering skills, I’m guessing they may have worked as prospectors too. Sometimes the prospectors also filled the role of miner, but generally, miners were the working stiffs who labored underground.

I hope I can enhance your appreciation for how physically demanding, noisy, wet, and uncomfortable the hardrock miners’ underground jobs were.

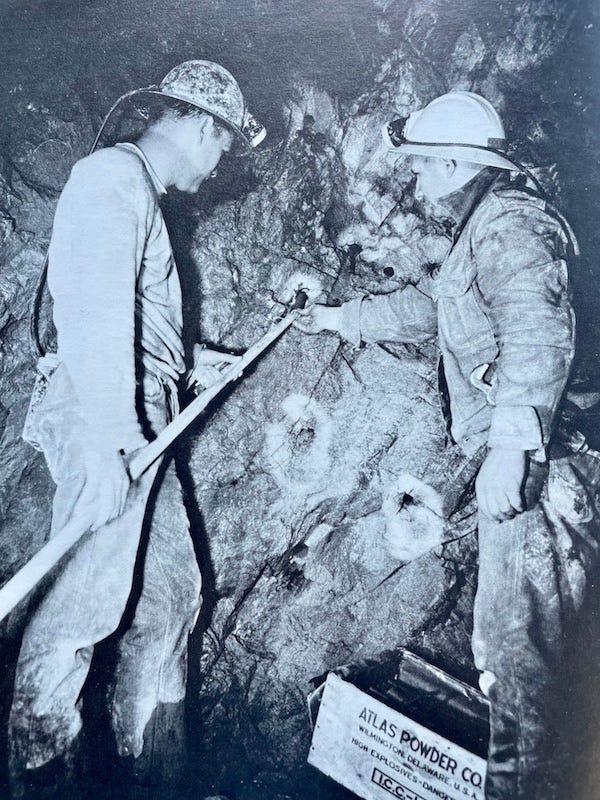

Basically, their job involved using different tools to chip away at rock to get to mineral veins, and then different mechanisms to haul out that ore and separate and sort the valuable minerals from the waste rock, which were called tailings.

It used to be that miners mostly hammered away at the rock manually, but the invention in the 1870s of a rock drill driven by compressed air allowed them to drill holes, fill the holes with dynamite powder, and blast at the rock. This made their job more efficient but also a lot more dangerous. The process of drilling caused rock dust to billow up and get in their lungs, and lung disease known as “miner’s consumption” sickened and killed many miners in the early days.

The mine operators improved this problem by fixing the drills to have a steady stream of water run down and wet the drill bit, to dampen the dust from rock fragments. But this made their working conditions perpetually wet and contributed to mud. Mel Griffiths described the miner’s environment this way:

“For all of its engineering orderliness, the underground workings of a mine is one of heavy industry’s dirtiest and noisiest environments. The thundering bellow of a drill at close hand is ear shattering. The narrow confines magnify the racket. Escaping exhaust air, having done its work, fills the passage with palpable fog. Water charged with dust and rock runs from drill holes like superating sores. Mud is everywhere, made by water delivered to the cutting head of the drill bit and mixed with seeping ground water which issues from fissures and seams in the rock. When the miner comes off shift, he removes his digging clothes in a change room, showers off, and changes into outside clothes. Digging clothes are usually so dirty and stiff they will stand alone in the middle of the floor if they aren’t hung on a peg.”

I first learned about hardrock mining from my grandfather, David S. Lavender, because he worked in the Camp Bird Mine during the Depression. Since you all will run along Camp Bird Road and see some of the remaining lower buildings from the camp, I want to share a bit of Camp Bird history. This is a picture of him and my grandmother in front of the mine in 1935, when he took her there to give her a tour. But he actually only worked there for one season, in early 1933, and then he devoted himself to helping to keep his stepfather’s ranch afloat during the Depression. His experience is told in detail in his wonderful memoir One Man’s West, which has been in print since first published in 1943. I encourage anyone with an interest in southwest Colorado history to read it.

My grandfather left Stanford law school in 1932 after just one year because he needed to earn money to marry my grandmother. His stepfather Ed Lavender pulled some strings to get him a job at Camp Bird, because jobs were so scarce.

My grandfather told me once, when I interviewed him before he died in 2003, “Camp Bird was about the only mine that was operating, and there was a constant stream of people trying to get job. I got $5 a day from which 20 cents a day was deducted for board and 5 cents for insurance. Union people would come up to try to organize the guys, and the miners themselves would run them off. They didn't like anything that might close the mine. The waiting line of people wanting jobs would have stretched from the Camp Bird to Ouray. Those were hard times.”

Camp Bird started in 1896 and flourished for 20 years, but then the increased cost of labor and material, combined with the flat price of gold, made it unprofitable, and it shut down in 1916. Then came the Depression, with lower labor costs, and the mine reopened on a smaller scale.

Grandpa said it was like working in a ghost town because he and the small army of workers—almost all of whom were immigrants from Europe with limited English—occupied only a small portion of the giant boarding house that had been built for 400 workers. One Man’s West includes vivid descriptions of what it was like to rent a horse at the Ouray livery stable and ride up to Camp Bird through avalanche danger, and then what it was like to live in the boarding house and work in the oppressive darkness of underground.

He had a job as a hoistman, working a hoist to haul up great loads of ore. In his memoir, he describes the danger of his job—how slippery it was working on the edge of a mine shaft, and how other miners frequently got injured or died because they grew complacent and careless. Grandpa said, “I stayed scared, and I stayed safe.”

Now I’ll end with a segue to the San Juan Mountaineers.

High-Altitude Athletics

My favorite chapter in my grandfather’s memoir is called High-Altitude Athletics because it describes how he and his peers took to the mountains not to work, but rather, to escape work and hardship, and it documents the growth of mountaineering in the late 1920s, with my great-uncle Dwight at the heart of the scene.

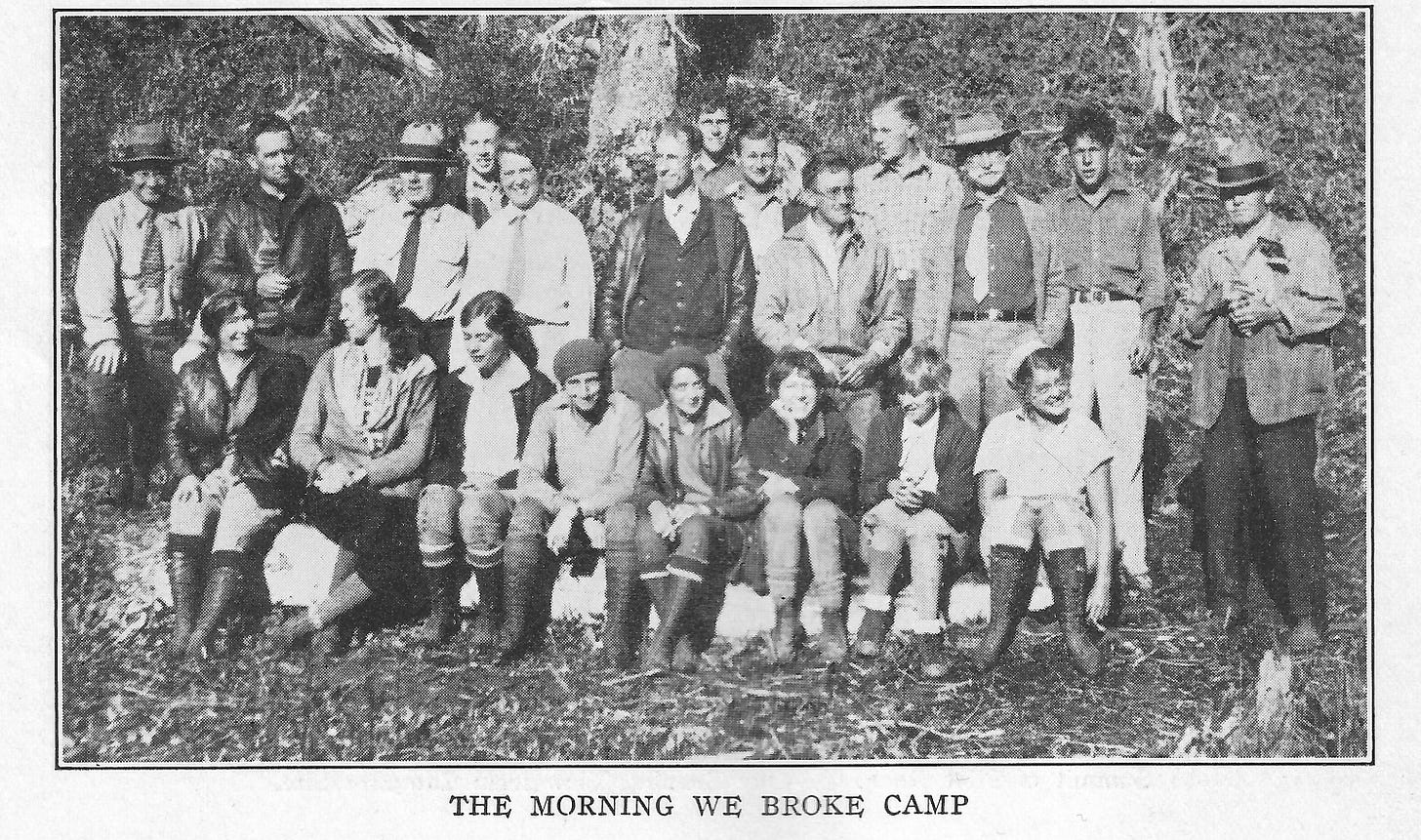

My grandmother wrote about one of these mountain outings in 1932 for the Colorado Mountain Club’s journal Trail and Timberline. She was named Martha but went by the nickname Brookie since her middle name was Middlebrooke. Raised in upstate New York, she met my grandfather on a blind date when she was studying at UC Berkeley and he was at Stanford.

After they got engaged, she spent the summer of 1932 at age 21 here doing a great deal of hiking and climbing, and she became the first woman on record on July 27, 1932, to summit the 14’er Sneffels via a particularly challenging north-facing line from Blaine Basin, which was covered with snow and ice.

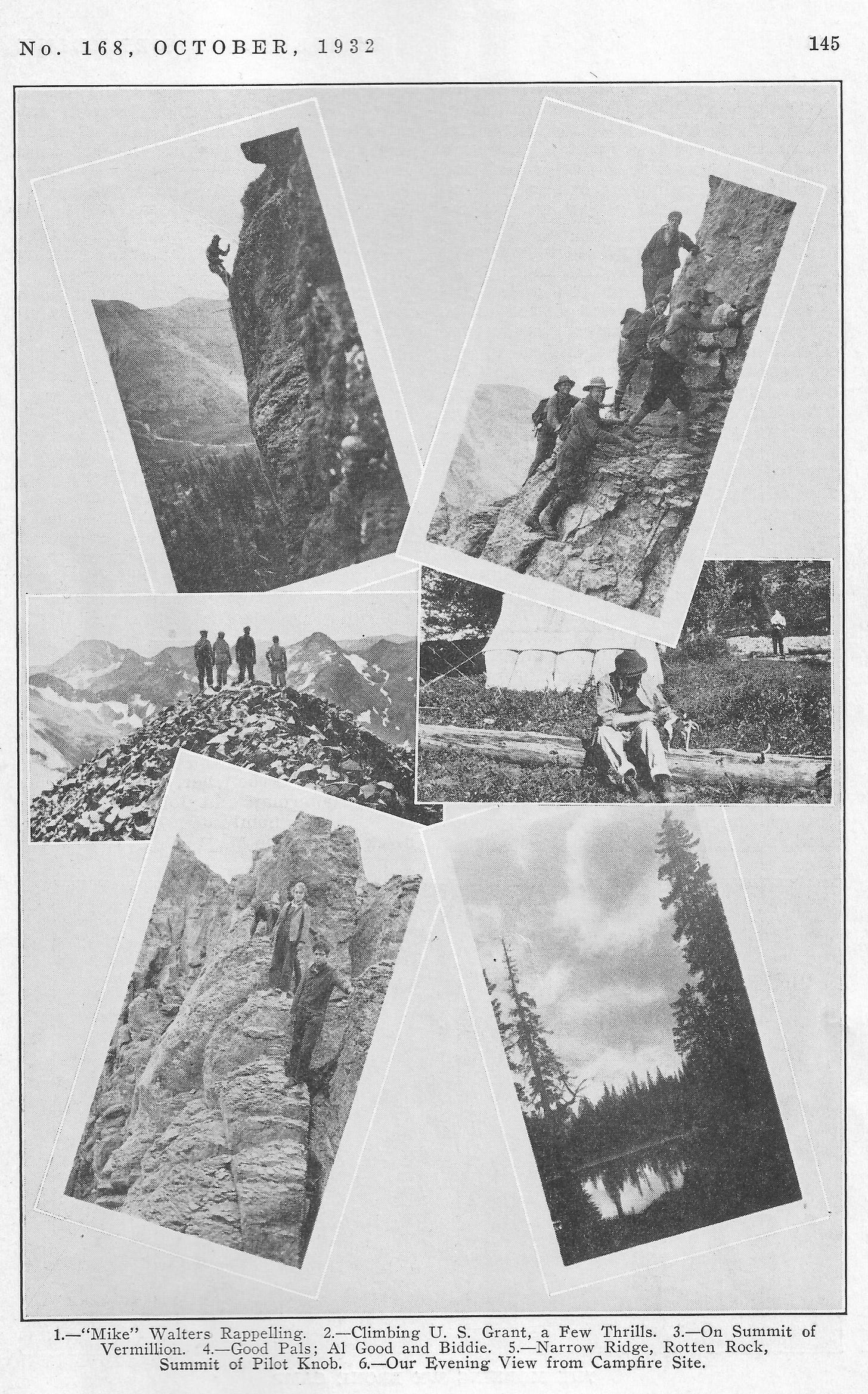

Then a week or so later in early August 1932, she and the group pictured here spent several days around Ice Lake Basin above Silverton summiting the 13’er U.S Grant Peak, which rises right next to Grant Swamp Pass, and they also climbed nearby Pilot Knob and Vermillion peaks.

I want to read an excerpt from Brookie Lavender’s article because you all will experience something similar as you make your way to Grant Swamp Pass on Friday, and I think it’s inspiring to imagine the first generation of mountain athletes—including women—doing something similar 90 years ago.

My grandmother wrote:

“One look at U.S. Grant rising sheer above Island Lake was all I needed to convince me that there is only one way to see the mountains—and that is to get out in them and climb, and puff and slip and slide in the scree. Naturally, the view of the peaks encircling the deep blue waters of Ice Lake only lured one on and on, throwing out both a challenge and an invitation—the challenge to the climber’s courage, endurance, and skill; the invitation to the dreamer to sit on the heights and gaze off through the keen clear air at the ever-changing panorama. …

It is a task surpassing any ability that I may have to describe my first climb. The pace that started out at what seemed so slow a rate suddenly became a dead run, or so it seemed to my New England lungs; the top that at first looked so near then seemed steadily to get farther away; and then, there was the scree—oh, that scree. I guess that the mere mention of the word is all that is needed, for I heard more than occasional murmurs coming from between the teeth of the more experienced climbers as they slipped and slithered even as did you and I. But it was all much more than worthwhile when at last we stood on the top.”

So, I hope that will inspire you to be gutsy as you slip and slide down the headwall of Grant Swamp Pass on Friday during the first day of the Hardrock 100 on your way to Chapman Gulch.

Thank you so much for reading this long post. I look forward to sharing Pete’s photos and stories about the San Juan Mountaineers in a future post.

Really great and interesting read. It's amazing how much civilization has changed, for better and for worse. It's always sad to read about how much of our prosperity was a result of taking land from Native Americans. If you've never read "Lasso the Wind" by Timothy Egan, I highly recommend it.

Nice historical summary. I know that a lot of the labor strife was mirrored in Butte, Montana. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, also called 'wobblies') made efforts to organize workers, which was not viewed favorably by mine owners. A lot of violence ensued.

One typo, in your caption for "The Surveyors". I assume that's 1873.

Martin Miller

Helena, MT