How to Plan a Peak Long Run

I needed an old wagon road plus Michelle Obama for a successful marathon-length workout

Welcome back. I admit, I struggled to produce this post because I kept hearing in my head, “Nobody wants to read about your long run.” Then I wasted a good chunk of time on the too-funny yaboyscottjurick Instagram account, thinking it’d have the perfect meme to illustrate this sentiment. I came up empty, but this one is close if I were the husband:

But no run is ever just a run, right? This one is a history lesson and a day trip, too.

I looked outside last Thursday and saw several feet of fresh snow nearly burying the meadow’s old picnic table. The brilliant pristine drifts spread out like a gift from the gods to the thirsty earth underneath.

But, to me, the snow posed a problem. Trails would be blanketed. Roads would be icy. Temps would be in the teens. And more snow would fall Saturday, the only day I had free to complete a long training run. Where would I run?

On most winter weekends, I can log a decent long run by running back and forth on a boring but cleared stretch of road, or I can hop on the treadmill and gut out a couple of hours with the help of an audiobook.

But the January 21 workout wasn’t an ordinary long run. It needed to be a peak long run—at least 5.5 hours in duration, pushing me past the marathon mark, stressing physical and mental stamina to build endurance for a 60K (37-mile) ultra four weeks away in Arizona.

Then it hit me, I could reframe the question of where to run as an opportunity rather than as a problem. And instead of thinking of it as a high-pressure workout, I could treat it as an easygoing day trip. Instead of running the same county roads near my house, I could go somewhere new and farther afield. Where do I get to explore?

Planning a peak long run

Peak long runs need to be confidence-builders. If you bonk, cut the run short, or spend miles debating whether you even want to start the race, then chances are you’ll line up to race with some combo of ambivalence and trepidation.

“Preparation is the key to success,” my first coach in the 1990s repeated often. OK, I would prepare. No winging it. I would come up with a plan and pack everything I’d need for support.

Step 1: Choose an inspiring and long-enough route

Ideally, I would run a route with terrain and an elevation profile that mimics the race I’m preparing for in Arizona, the Black Canyon 60K. For this reason, I considered driving two to three hours each way to run high-desert trails near Moab or Grand Junction. But I heard those trails were soggy and slushy from rain and snow, and I did not want to tackle a mud bog. Better to find a road with a layer of hard-packed snow.

I also did not want to spend too much time driving. Being short on time and feeling rushed can sabotage a long run, letting you rationalize cutting back the final hour in order to get home on time. I therefore looked for a good, new, extra-long route two hours or less from home.

I surveyed a map of our region and asked myself, where am I itching to go? Where have I not been?

Dave Wood—the man and the road

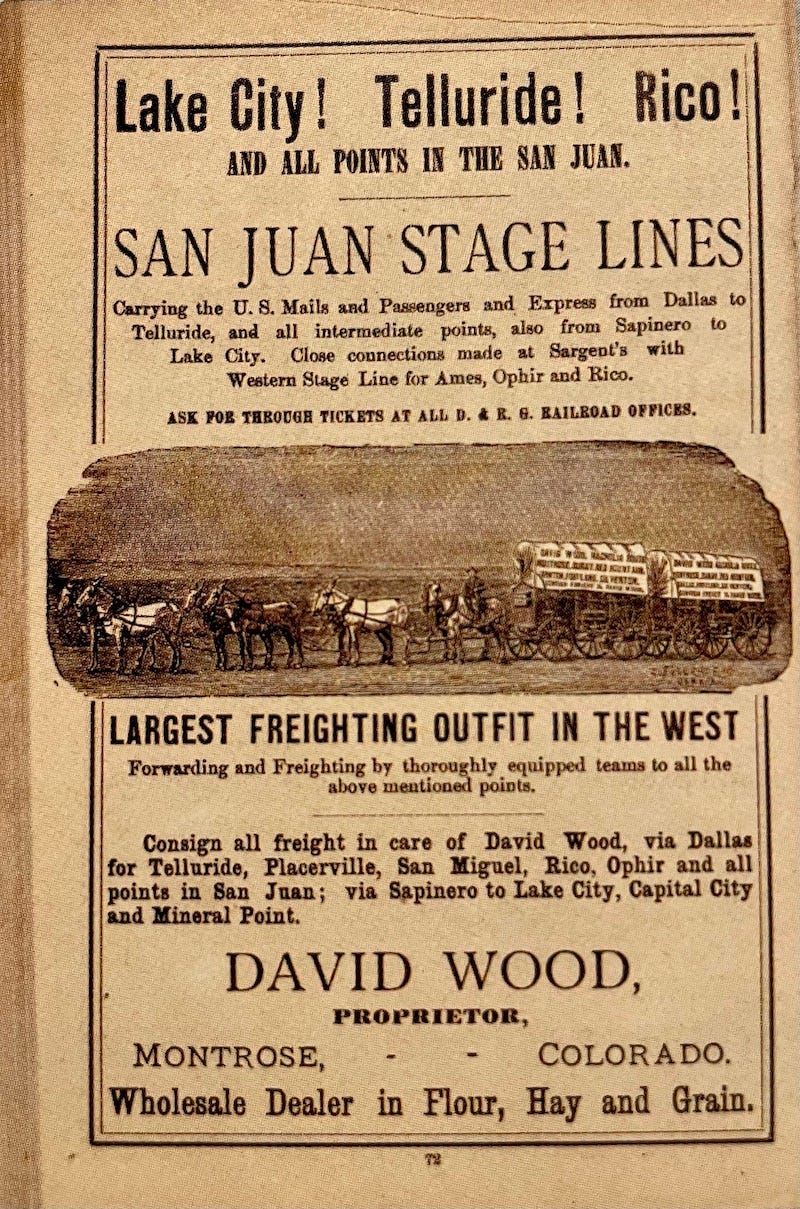

Fortuitously, a copy of Telluride Magazine has been lying on our kitchen island, and I recently read its article about a pioneer named Dave Wood. The story of this industrious man and his times captured my imagination and, ultimately, gave me a destination for Saturday’s run.

At age 25, Dave Wood came to the Centennial State from Kansas in the centennial year, 1876, not to strike it rich with gold or silver, but to find opportunity in the supply chain. Someone, he realized, needed to get people and goods from the end of the line of the new railroad to all the mining camps springing up in the mountains, and then haul ore from the camps to the railroads.

He settled in Montrose and became that guy, the one who invested in wagons and horses and developed routes to travel to Ouray, Silverton, Telluride, and other new mining towns. But the expansion of the railroad kept cutting into his freighting business, so he kept developing and marketing new, more efficient routes around the mountains where the railroad didn’t go.

I have a special interest in this time in history, not only because of my childhood obsession with the Little House books and their depictions of a girl and her family homesteading, but also because that is when my great-great grandfather, Charles Painter, moved to Telluride and became a key person establishing the town (then called Columbia) as the first mayor, county clerk, and newspaper publisher. Like Dave Wood, Charles Painter was an entrepreneur seeking business opportunities in the brand-new mining camps that were evolving into towns.

I figured Charles and Dave must have been peers who did business together, and sure enough, the magazine article quotes an 1885 letter between them. Charles had run out of paper to print the newspaper, so he asked Dave to bring some as soon as possible. Charles wrote, “Just got a bill for twenty bundles of paper, which ought to be in Montrose any day now—will you at once, upon receipt of same, take out one bundle and ship by Express as we are completely out?”

I drive back and forth from Telluride to the bigger town of Montrose weekly for errands (Montrose has a City Market and big-box stores, plus a lower-elevation bike path that’s nice and easy to run). It’s a 62-mile trip one way that takes about 1 hour, 20 minutes. The railroad used to follow this highway route through Ridgway. It’s also the way Dave Wood initially traveled between Montrose and Telluride during the first phase of his business, which meant he had to pay a toll to the railroad’s builder and boss, Otto Mears.

But Dave didn’t like the route, which seemed unnecessarily long—like going two sides of a triangle—nor did he like the railroad’s toll. In 1883, therefore, he developed the idea for a 33-mile shortcut that would connect Montrose to the base of the Norwood Hill, which would be a more direct route to drive his wagons to the San Miguel Valley leading to Telluride.

“Wood’s Cut-Off” it was called then, and Dave Wood Road it’s called today. For whatever reason, I had never been on it. But I have occasionally read news snippets or received county emergency alerts to avoid Dave Wood Road, because hapless drivers get stuck in strong winter conditions along it after Google Maps sends them that way.

Dave Wood Road, created with the can-do pioneering spirit of the late 19th-century, seemed like the perfect route for an extra-long run.

But I really didn’t know what to expect.

Step 2: Get all your shit together

Prepping for an extra-long solo run takes thought and time, so I got most everything ready the night before. The checklist looks like:

charge watch, phone, AirPods

pack hydration pack (fluids, snacks, comfort items like toilet paper and anti-chafe lube, basic first aid, Garmin InReach for safety & tracking in case I’m out of cell range)

pack a cooler with more substantial food and drink (in the morning, I heated up a can of chicken noodle soup, plus leftover veggie chili, to put in Yeti mugs to have midway and after the run; I also packed several cans of sparkling water)

figure out what to wear, and dress in layers to accommodate swings in temperature

pack a bag with a towel and change of clothes to freshen up and get out of sweaty clothes right after the run

download and queue up podcasts/audiobook/playlists for listening

Just as importantly, I had to prep mentally. I had to commit to the duration—that I’d be out there for over 5 hours and get past the 26-mile marathon mark. I also had to make sure my husband was OK with the plan for me to be gone all day. As couples know, this takes negotiation and tradeoffs; I would also plan time for us to be together over the weekend and time for him to have a long break skiing. I have learned to build a time cushion into estimating how long I’ll be gone, rather than being overly optimistic and promising to be home by a certain time, which creates stress that can sabotage going the distance in a long run.

I also mentally devised a Plan B; if the road condition was too awful for whatever reason, then I’d make peace with backtracking toward Montrose and running familiar roads around town.

Step 3: Do the damn thing

I drove southwest of Montrose to the start of Dave Wood Road, planning to park midway out on the road so I could do a southward out-and-back, then return to my car and use it as an aid station, then finish the run with a northward out-and-back.

The first thing I noticed were the BLM trailheads branching out from the road. How and why have I never run out here? It made me excited to return in early summer (before it gets too hot) to discover this trail network.

The second thing I noticed: the road looked and felt a little desolate, a little spooky. A heavy cloud layer obscured the sun and the views of the San Juan and La Sal mountains. The temperature hovered around 20 but felt colder. I could see nothing but piñon and juniper bush lining the snow-covered road.

I thought of Dave Wood and his wagons out here, cutting a route through brush and trees in all kinds of weather conditions and acting like a diplomat (at least, I hope he acted diplomatically) when confronting the Utes who were losing their land to settlers. Be brave like Dave, I told myself.

I parked near the Mile 7 marker, near the “Pavement Ends” sign,” and started running, endeavoring to cultivate patience. Be in the mile you’re in.

With each mile, the snow underfoot grew deeper. Fortunately, vehicles periodically drove by, likely en route to an area popular for snowmobiling and snowshoeing, so I could run in the vehicle’s tire track for better footing. But these vehicles drove fast and carelessly, not expecting to see anyone on the road, so I had to stay highly attuned to approaching cars and move way out of their way for safety. This meant I could not lose myself in music; I needed to keep my ears open, not plugged with AirPods.

I decided to listen to an audiobook playing on the speaker of my iPhone tucked into the hydration vest pocket, so I could hear the narration well enough but also hear approaching cars. I chose Michelle Obama’s new book, The Light We Carry, because I got so much out of her first book, Becoming. Michelle Obama, who is the reader for the audiobook version, thus became my soothing, encouraging friend on this run. I am not big on self-help books, but her advice mixed with storytelling infused me with motivation and positivity, just what I needed to navigate this lonely old wagon road.

The road climbed more than I expected it would. Silly me, I should have known the road goes up and over the Uncompahgre Plateau, which sits at an elevation over 9000 feet, but still, the 2000-foot ascent surprised me and prompted more hiking breaks than I had planned for. I ran what I could and hiked what felt too stressful to run, settling into an average pace of 11 to 13 minutes per mile. Tortoise pace.

When I started feeling discouraged after two hours, having covered only around 9 miles uphill (so slow, the voice in my head said), Michelle told a story of a coping mechanism she discovered at the start of the pandemic’s shutdown. Always an ambitious go-getter with an endless to-do list, she had never felt drawn to simple hobbies. But the pandemic forced us all to slow down and stay put, so like many, she took up knitting. The small act of knitting became for her a way to feel a sense of simple accomplishment, along with calmness, while working through bigger problems and managing worries in her head.

Her description of knitting sounded a lot like my practice of long runs, insofar as it allows for time and headspace to think and engage the imagination. It also involves a leap of faith when starting the run, not knowing exactly where the run may take you or how it will feel, but having the endurance, determination, and patience to find out and finish.

“You have to be OK with not knowing exactly how things will turn out,” Michelle Obama wrote and then narrated from the phone in my pocket. “In knitting, you cast on your first stitch and follow a chart—a series of letters and numbers that to a non-knitter might appear cryptic and unreadable—and the chart tells you which stitches to lay down in what order. But it takes a while before you can see anything adding up, before the pattern itself becomes visible in the yarn. Until then, you just move your hands, and follow the steps, and in this way, it’s kind of an act of faith … we practice our faith in the smallest of ways, and in practicing it, we remember what’s possible. With it, we are saying, I can. We are saying, I care. We are not giving up. In knitting as with so much in life, I’ve learned that the only way to get to your larger answer is by laying one little stitch at a time. You stitch and stitch and stitch again, until you’ve finished a row. You stitch your second row above your first, and your third row above your second … and eventually, with effort and patience, you begin to glimpse the form itself. You see some kind of answer, that thing you hoped for, a new arrangement taking shape in your hands.”

My mantra for the run became, step by step, mile by mile; stitch by stitch, row by row.

After cresting the plateau, I turned around and ran two more hours back to the car—easier downhill miles, hardly any breaks. I felt more smiley and less suspicious toward the vehicles that passed. When I reached the car, I was 20 miles into the run at around 1:30 p.m., craving lunch, so I eagerly consumed the still-warm chicken noodle soup I had packed. Then I forced myself to leave the car and head out for at least 90 more minutes.

I run 100-milers, so 27ish should be no big deal, right? But it is. It never gets easy, especially when running solo and self-supported on snowy tracks in thin air.

“The magic happens in the final hour,” I used to advise clients whom I coached, explaining the importance of not cutting a long training run short. It’s during these final miles when we push past our limits of endurance, stress and deplete our internal systems so they will recover and adapt to be stronger, and develop mental fortitude and patience. I reminded myself of that advice, and of the fact that the upcoming race would take me around 8 hours, so a training run of roughly two-thirds that duration should be manageable. I got this.

The final couple of miles featured an 800-foot climb back to the car. My upper right hamstring ached. My lungs felt raspy from the cold air. My entire posterior chain of muscles felt tight and achy. But I was making it, stitch by stitch. And I experienced no run-stopping problems. My feet felt fine, surprisingly, as did my hands, face, stomach (albeit hungry), and so much more. By focusing on what felt fine—and imagining the mug full of chili waiting in the car—I could keep going.

I willed myself to run rather than hike the last uphill mile, leaving nothing in my tank. I reached the car right at 5 hours, 30 minutes, and my watch read 27.1 miles. Mission accomplished!

As far as long runs go, this one wasn’t “epic” or “gnarly” or any other adjective sometimes applied to peak long runs, and I didn’t cross the threshold to enter the metaphoric “pain cave.” It was just a steady, interesting, inspiring, solid-effort marathon-length run with hiking mixed in, as fulfilling as it was depleting. And that’s exactly the kind of peak long run I’d like four weeks before an ultra, to build confidence that I can go the longer distance on race day.

It also felt like a special day trip and history tour. I’m grateful for the opportunity to discover new places through running, and I’ll definitely return to explore the trails once the snow melts.

Hats off to Dave Wood and his legacy. Anytime I feel tired and think that something is physically difficult, I need only remember the working conditions of 19th-century pioneers to this area. If you’d like to read more about the people and circumstances of that time, check out my earlier history post, “Digging Into the San Juan Mountains.”

Related posts:

Also, please comment below or join the Chat thread to discuss!

what a great read and a great run... although I had to laugh at your tortoise pace (11-13) that's my "I'm doing great pace"....ha!

27 miles in the snow is a big day! Definitely a character builder run, and great mental fuel for your upcoming race.

I really love how you weave history into your running stories. I wish I had the drive and curiosity to do more research behind some of the local routes here in Oregon. We've definitely got it pretty easy compared to the frontier days.