Hardrock's Epilogue

Fun & adventure ensued after the event ended, shedding light on what makes it so special and tough

Welcome back! Tomorrow, I host the monthly online meetup for paid subscribers—a casual conversation via Zoom where we talk about each other’s training, races, and various aspects of wellness. Please consider upgrading your subscription to the supporter level if you’d like to join these meetups and receive occasional bonus posts. You also can earn a comp’ed subscription by referring people to this newsletter. If you’re a free subscriber or reading this for the first time, thanks for being here.

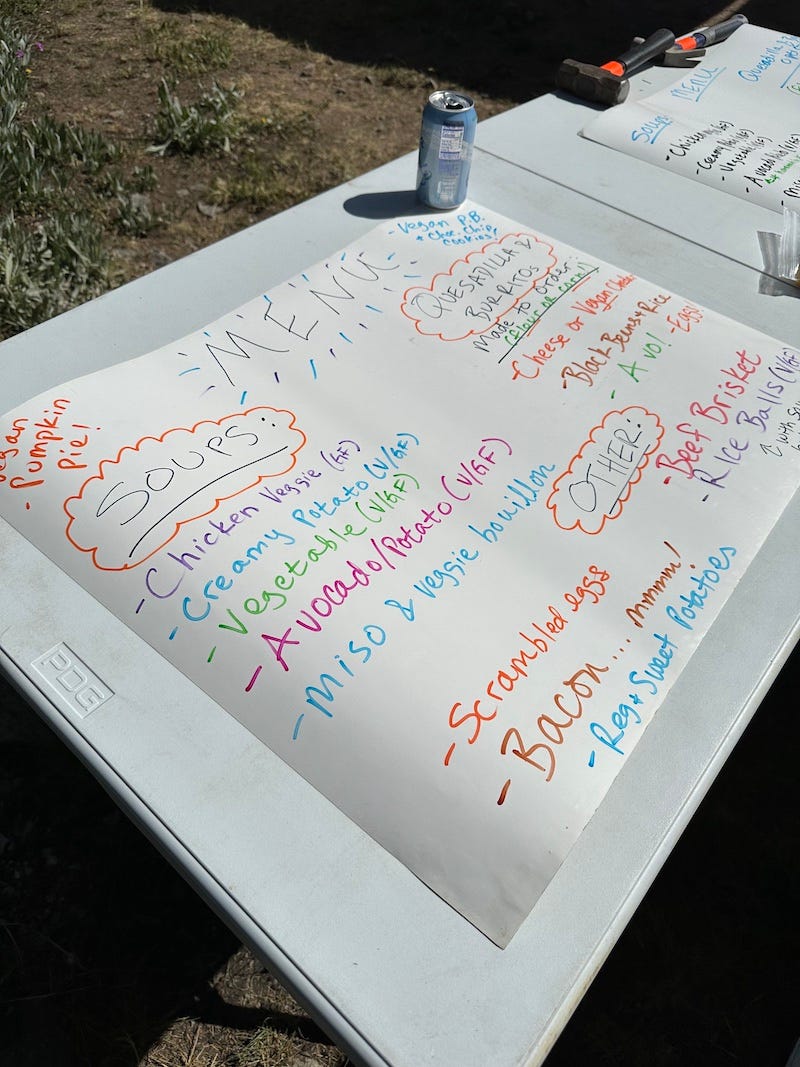

I spent last Friday through Saturday immersed in the Hardrock 100 as an aid station volunteer. I worked during the day to help set up a base camp with a full kitchen and medical tent to support runners, then worked until 2:30 a.m. to support them as they came into the aid station exhausted and in need of food, hydration, foot care, and rest. Saturday morning, we all pitched in to break down the aid station and leave no trace of our big footprint in the wilderness.

In this year’s counter-clockwise running of the event, the Animus Forks aid station was at Mile 44 on the route. Runners came to our spot—a remote location at 11,000 feet elevation outside of Silverton—having just traversed the 14’er Handies Peak, and several were dehydrated and out of sorts due to last Friday’s unusually strong heat and cloudless sky.

I decided not to write about this aid station experience, however, because I detailed it last year (“Anatomy of an Aid Station”). I’m also not going to write much about the race itself, because you can find loads of coverage on iRunFar.com, trailrunnermag.com, or watch the archived livestream on Run Steep Get High’s YouTube channel. (Plus, I barely followed the race as it unfolded in its second half, because I had no cell coverage at the aid station and was focused on the tasks at hand.)

Instead, I want to share two stories that I hope convey the Hardrock spirit of community along with the difficulty of the route.

People less familiar with this 102.5-mile event, which began in 1992 and has over 33,000 feet of vertical gain through the San Juan Mountains on a route linking Silverton-Ouray-Telluride, might wonder: What’s the big deal? Why do so many want to run it and describe it as so special? Why do so-called “runners” hike so much of it so slowly, struggling to make the 48-hour cutoff (an average pace of about 28 minutes/mile)? What makes it live up to its motto “wild & tough”?

First, let me tell you about a coda to Hardrock, which captures some of the characters and their ethos. Then I’ll share a slice of the route.

Going the extra mile

After returning home Saturday midday to rest, I woke up extra early on Sunday morning to drive the 1 hour, 45 minutes back to Silverton. I wanted to watch Hardrock’s post-race awards celebration and then spend a few hours volunteering more at the race headquarters.

But first, I felt compelled to do something both uncomfortable and heartening. Something with the potential to feel awkward and/or uplifting.

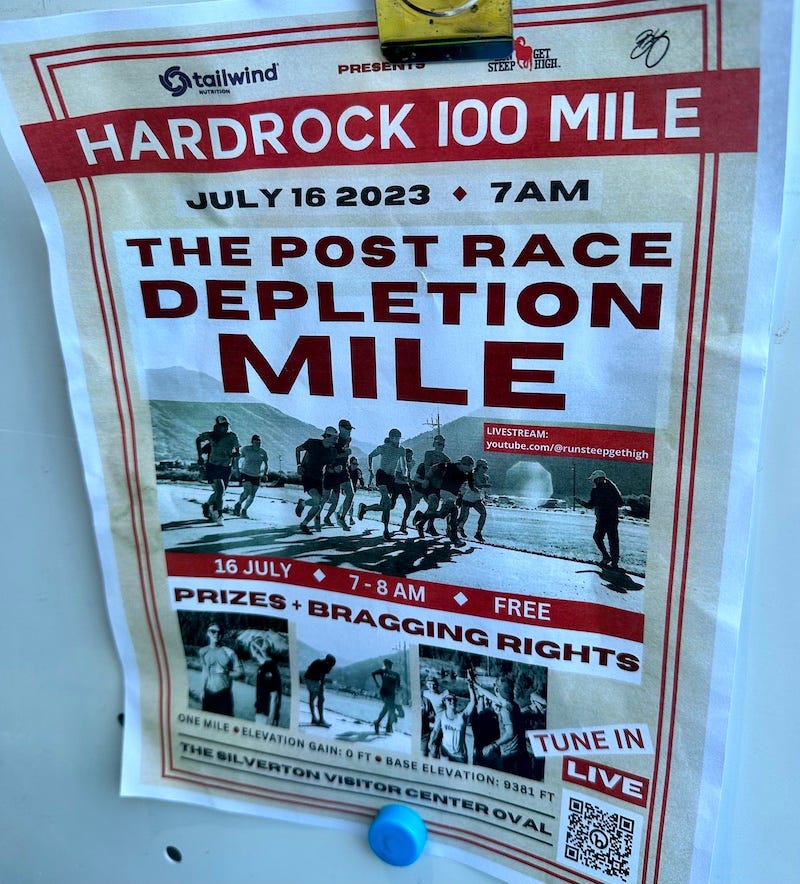

I showed up for a celebratory pseudo-race for Hardrock competitors and for anyone else who wants to run—volunteers, friends, locals, dogs. It was the free, loosely organized “Post-Race Depletion Mile.”

I saw only a dozen or so cars parked when I arrived at 6:30 a.m. at a track behind Silverton’s Visitor Center. I was expecting a standard track with a rubberized or dirt surface, but this oval—which is close to, but not exactly, 400 meters—is covered with old asphalt, weeds sprouting in its many cracks.

I felt nervous, as if arriving too early to crash a party. What am I doing here? The realization that I was about to put my slow running on display suddenly seemed like a very bad idea. I wished I had a shirt that read, “I used to run miles in the low 6’s.” I have not run on an oval track in eight months (as detailed in this post from mid-October about a special speed workout).

Then I absorbed the beauty of daybreak in this old mining town. The 13,000-foot Kendall Mountain—which I raced up and down the prior weekend—loomed over the scene, giving me confidence but also making me feel tiny and insignificant. We’re all small, fleeting creatures in the context of these massive, prehistoric mountains.

I looked out the car window at the track and it hit me, Nobody cares about your time or your pace. Just run to run. Carpe diem!

I spotted a familiar black Subaru with California plates arriving, belonging to Billy Yang, one of the organizers of this fun run. I was happy to see him and his wife Hilary. Then I found Maggie Guterl doing her job repping Tailwind and setting up product on a table. We chatted, and I tossed my sweatshirt on the ground to start a warmup mile. A few young guys already were warming up around the track. More people gathered, about half of whom I recognized.

A shirtless Mike Wardian approached from behind. Mike holds multiple records for a variety of distances and terrain, and he had finished Hardrock the prior afternoon in 20th place in a very respectable 34 hours, 26 minutes. He’s the one responsible for starting this “depletion mile” event with a couple other guys in 2017 as a friendly challenge and way to loosen up tired legs after a 100-mile effort.

He called out, “Sarah, your form looks really good!” I flushed with mild embarrassment and pleasure at this overblown but sincere-sounding compliment. We paused on the track for a quick hug. We got to know each other years ago at races, and last year I shared some miles with him outside of Montrose during his transcontinental run from California to Delaware.

I rejoined the growing group after four warmup laps and spotted the champ herself—Courtney Dauwalter, who had just broken Hardrock’s longstanding women’s course record in the counter-clockwise direction (she holds the record in the other direction, too) and three weeks prior had set a new course record at the Western States 100.

When Courtney saw me, she made her characteristic funny face of bug eyes and a dropped jaw. She asked, “Hey! How are you?” and pulled me into a hug. A Courtney hug! Just like she did from the sidelines of the 2021 High Lonesome, planting in my mind a mantra, Run like Courtney, which to me means: run with positivity, humility, humor, determination.

I laughed, somewhat disbelieving that someone of her stature remembers me (we had met and talked back in 2017, and I’ve interviewed her a few times). “Um, more importantly,” I asked, “how are you?” She smiled and said, “Great!” She thanked me for being at the aid station supporting runners. She looked happy and relaxed, and as always, normal and down to earth. One of her superpowers is genuine interest in everyone around her.

Then I went over to congratulate third-place finisher Annie Hughes, Hardrock’s youngest competitor at 25, and to tell her how impressed I was that she persevered through multiple physical problems in the race. When I saw her at Animus Forks on Friday afternoon, she looked overheated, in pain, and disappointed that the two lead women were quite a ways ahead of her. Now, at the track, she seemed like her normal cheerful self. Only her sunburned face and swollen feet in rubber slider sandals hinted at the exhausting 100-miler. Amazingly, she would zoom around the four laps of the mile in those sandals.

Billy hollered at everyone to line up to start. Maybe 30 or so runners gathered (nobody took an official count or registered who was there). Several more Hardrock runners and their crew, along with locals and visitors, stood on the side to cheer.

I took my place next to a twentysomething woman in braids like mine named Molly, with whom I had volunteered at Animus Forks, and her mom, who looked close in age to me. Silver-haired Rick Hodges took his mark and got set nearby. He had attempted to finish Hardrock for his 15th time but had missed the time cutoff at Telluride, Mile 74.

Maggie, Annie, Mike, Arlen (the 5th place finisher), and numerous younger speedsters lined up in the front; Courtney and her husband Kevin tucked in the back. Oddly and wonderfully, nothing felt intimidating about this starting line. I and others only seemed to feel a giddy anticipation. I felt cocooned and supported in this circle of all-ages, all-abilities, all-tired-from-the-weekend runners. This was not a cool-kids clique as I had feared it might be, because nobody acted cool or pretentious. We all were there to run, however we felt and at whatever pace we could muster individually.

Billy counted down and yelled “go!” and we surged forward. I took off as if running the 50-yard dash in grade school, and by 200 meters, my watch beeped with a reading of “+9” indicating the effort level. On regular speed sessions, I typically get it up to only +4. My limbs felt tingly with hypoxia. I knew I had to dial back the pace, but this felt crazy fun, even as the faster runners streamed ahead and opened a wide gap. I managed to catch and pass Hilary Yang only because her dog Charlie, who was running with her, stopped to poop.

This old asphalt track proved to be a great uniter. It didn’t matter how fast or slow anyone ran, only that we were doing it as a final hurrah to the superlative event that is Hardrock. It also didn’t matter that I and others weren’t actual Hardrock competitors. (I haven’t run Hardrock yet because I haven’t been able to gain a spot through the longshot lottery.) As long as we were involved in supporting it in some way—be it as a volunteer, pacer, crew member, local business, passer-by, or whatever—we were welcome. The awards ceremony that followed this mile similarly celebrated everyone, not just the top finishers.

I ran each lap emboldened and endeavoring to stride out on the straightaways. People on the infield held out their hands for high-fives. I felt wobbly but pushed on. Just as I started the fourth and final lap, I heard cheers for Mike Wardian, who nearly lapped me and finished his mile in just under 6 minutes.

But I wasn’t at the very back of the pack. There were some shufflers doing their own thing, including a stiff-legged Courtney, who seemed content to jog. She had nothing to prove.

Below is a short clip of me transitioning to my third lap, then one of Courtney and her husband Kevin:

I finished in around 7:50, happy to log a sub-8 mile (which no longer feels easy for me, especially at 9300’ elevation). Everyone turned to watch the final runners come around the track, and someone yelled “Quick, make an arch!” Two lines formed, each of us reaching out to touch the hands of the person across from us.

My fingers connected with those of Blake Wood, 64, a legendary runner who finished Hardrock 22 times between 1994 to 2018 but DNF’ed the last two times he attempted it. I had seen him get in and out of the Animus Forks Aid Station at around 2:20 a.m., all business and determination with only 10 minutes to spare before the cutoff, and then he dropped at Ouray because of missing the cutoff there. I felt envy mixed with admiration, because he’s been able to run Hardrock so many times, but mostly gratitude that he developed Hardrock into what it is today and that he’s a role model for older runners to keep at it. He came back to run this mile on this morning in spite of the disappointment 24 hours earlier, showing he’s still running strong.

All of us making the arch, and everyone on the sidelines, cheered “Courtney!” as she came out of the final curve and jogged toward us. Then she hunched over to run under our arms. In what other sport, in what other venue, would a world-class athlete and her fans get to do such a thing together?

The cheers continued and grew louder for the final runner, Rick Hodges, age 74. I thought to myself, That may be me in 20 years, if I’m lucky.

A lot of people talk about how ultrarunning’s community has been diluted by the sport’s growth and professionalism, but not here at Hardrock. I felt a sense of community and acceptance increasingly rare in regular everyday society. The setting of Silverton’s dilapidated track, which is open to all instead of fenced off, combined with the communal desire to run—to chase and celebrate the paradox of fulfillment through physical depletion—bridged divides and forged friendships.

You can watch the blow-by-blow livestream of the Depletion Mile here. The post-mile casual conversations captured on film are wonderful to eavesdrop.

What makes Hardrock a “Hardwalk”

The next day, Monday, I woke up motivated by the Hardrock finishers and feeling that I had a mission to complete. I had to tackle Grant Swamp Pass on the Hardrock course, solo, to prove I still can do it.

I’ll share the account because people who follow Hardrock—but never get to visit and run the route—sincerely wonder what makes it so hard. How is it possible that some miles take up to 45 minutes? Why do talented runners run so slowly even on downhill portions?

If you traverse Grant Swamp Pass, you’ll discover why. It and Virginius Pass (site of Kroger’s Canteen Aid Station) are arguably the two most challenging and technical parts of the Hardrock 100 course, both hitting 13,000 feet elevation. (Handies Peak, the 14’er, is higher but easier to traverse thanks to its relatively smooth trail.)

Grant Swamp Pass is a massive headwall made of chunky rock and loose scree that looms over a canyon where the mining town of Ophir sits. In this year’s counter-clockwise route direction, it comes at about Mile 87, when runners are exhausted. Having seen how spent and slow so many runners looked at my aid station, Mile 44, and knowing they still managed to get over Grant Swamp Pass and finish the race, fortified my resolve to practice ascending and descending it on my own.

I’ve been up and down it only six times prior, always with someone else. I’m still awed and fearful of it because of the potential to slide and tumble like the innumerable rocks that never cease to roll down its sides.

Getting to the base of the headwall from Ophir is a challenging but manageable and beautiful uphill trek that passes by seasonal waterfalls and wildflowers. A couple of miles above the aid station known as Chapman Gulch sits a grassy knoll at the base of the headwall where I always pause to contemplate several things: What is the best, safest way up? How will I get back down? How is this headwall even still standing, given that every single person who goes up and down it triggers a rockslide? Where does all of this massive, endless rock come from?

I could see that the Hardrock participants had chosen a route up the middle, capped with snow where snow steps had been dug. I decided to pursue that line, but I dreaded sliding back down it.

Fortifying my resolve, I took the first steps up the loose scree. Some of the rocks are fine and pebbly like kitty litter, while some are large and jagged like a spiky baseball. My eyes looked for faint indents that suggested a foothold. Slowly I made it upwards, each step feeling hard-won. At a certain point, trekking poles became less useful than bending down and using hands, grabbing anything semi-stable.

Other runners and climbers don’t think this ascent is such a big deal, but my fear of slipping and tumbling kept adrenaline flowing through my veins and kept my body close to the loose-rock wall, crawling, and testing each step for stability before reaching forward. At times, progress could be measured in inches, not feet.

Eventually, after at least five minutes at a snail’s pace, I reached the snowfield. I could see the steps that others used, and I started to follow them, but my foot immediately slipped in the slushy, soft snow. I didn’t trust it at all. I therefore went right, to the rocky rim, and used my hands to climb and inch up the rock to the ridge.

Here’s a photo from iRunFar showing one of the lead men going up Grant Swamp Pass’s snowfield on Friday at dusk:

And here’s a photo showing the green line I took up and the yellow one I chose to go back down:

I took nearly 10 minutes to get to the top. Eagerly, I scrambled up the lip of the ridge to see the other side—the rewarding view of Island Lake.

One of the most photographed and Instagrammed scenes from the San Juan Mountains, Island Lake never fails to dazzle. Its vivid bright blue is gem-like, precious and rare. Its dark round island sits like an iris in the eye-shaped lake. I picture it as a giant eye watching me and everything else that passes by through the centuries.

I ran and skid down the headwall’s backside to reach the lake’s shore, where I took a break and contemplated the scene and the passage of time. How can an eye-shaped reflective lake not prompt reflection as its gaze penetrates the soul?

I thought of my grandparents, who in 1932 in their early twenties came up here on a Colorado Mountain Club outing and bravely scrambled up to summit U.S. Grant and Vermillion peaks, which form the backdrop to Island Lake (as recounted toward the end of this post). Will I have a grandchild someday who hikes to this point and marvels at the scenery as I do? Will such a thing as snow still streak its sides? Will this lake—long ago likely covered by an ice sheet like a giant eyelid—evaporate, the island becoming a landlocked mound?

I marveled and soaked in the view, not taking for granted that it’ll look this brilliant when or if I return. Then I mustered energy to get back up to the headwall’s ridge and slide down the other side.

The way I came up was too difficult and scary for me to go down. I had to descend one of the snow-topped lines. But I did not trust myself to stand and step down the snow. I knew my feet would slip out from under me, so I began by sitting on my butt, sliding and reverse crab-walking down the cornice of icy, slushy snow. My hands grew numb, and snow packed my shorts, but gradually I made it to the scree part of the headwall without losing control. Again, my progress could be measured in inches, even though I was descending.

Once on the steep scree field, I tried to follow earlier advice that I should put my toes up, heels down, lean back, and go with the flow of sliding. But I completely lost my footing and landed on my tailbone four times, sliding down the mountainside as part of a mini-rockslide. Somehow, I thought, I have to get better at this.

Gravity did its job, and finally I stood on the grassy knoll below the headwall. My legs felt shaky, my backside raw, my knuckles bloody. I should start running, I told myself, but it’s not easy to run downhill when the terrain is loose rock.

So I hiked-shuffled-jogged the way down, admiring marmots and columbine, wondering if I’ll ever get to do this route as part of the full Hardrock 100.

I shared this to give context to the Hardrock Hundred Endurance Run—what makes parts of it so challenging, at times a full-body experience—and why it humbles even the toughest mountain athletes.

There’s hard, and then there’s Hardrock-hard.

Thanks for reading this long narrative! I’ll end with a photo dump from the aid station.

That's my picture from Grant's Swamp Pass. I was volunteering for IRunFar. I was there from about 9pm Friday until Noon Saturday.

The snow was soft when I arrived as the day was quite warm, close to 80 in Silverton, which was approaching a record.

By the time the first runners came through, around 1am, it was quite firm and it was nerve wracking to watch them come up the icy snow field.

I was planning on coming to the Depletion Mile but after seeing the final finishers I went back to sleep.

I've been wondering lately why I should keep trying for a shot at Hardrock, but this post gave me a clear and welcome reminder. Everything you say matches what I experienced when I was there as a pacer in 2017, from the casual mingling of everyone with everyone, to forcing myself up those high passes that took me way out of my comfort zone (in terms of both exposure and physicality). I guess I'll keep putting my name in the hat for a while longer. Thanks.