Hi there! Before we get to this week’s story, I have a couple of short notes. First, thanks to all who filled out my reader survey. The feedback—both encouragement and constructive criticism—is super helpful. If you’re a subscriber (not a one-time visitor), I’d deeply appreciate if you would fill out this reader survey. It should take five or so minutes to complete. As an incentive, I’ll draw two respondents at random to win an item of their choosing priced at $20 or less from the semi-rad.com store (which is full of fun stuff). Please reply before September 18, thank you.

Also, from Friday afternoon, September 22, through Sunday, September 24, I’ll be in Silverton participating in a special weekend women’s camp organized by The North Face and the Hardrock Hundred to spread knowledge and support for women running Hardrock (or any tough mountain ultra). Here are the details and registration link. You don’t have to commit to the whole weekend; you could attend for just one day if you like. I hope you’ll consider joining me there!

I’m tapering for Run Rabbit Run 100 in nine days. Normally, while tapering for a big goal race, I advise doing nothing risky that could be extra fatiguing or trigger an injury; for example, don’t use the extra time from reduced running for household projects such as cleaning out a closet, or you could strain your back by lifting boxes, which I did once before a 50K. Or, don’t impulsively hop on the neighbor’s green horse and get bucked off and break a vertebrae, which happened to me the week before 2019’s Bighorn 100.

But last weekend, I ignored my advice and risked falling and ankle-rolling for the sake of summiting a special peak with my daughter and husband. This is what happened.

I was hugging a rock face, arms stretched as wide as they could go, fingers waving across the surface for a crack or bump to grab. Once my hand found a hold, I peeked down at my feet to see if I could move one foot laterally onto an edge that would hold weight.

To my left, my 25-year-old daughter Colly stood on a stable ledge, coaching me as to where to move my limbs and find a hold. To my right, my husband Morgan clung to another rock face with confidence I wish I felt.

I told them, “Give me a sec, I’m feeling scared for the first time.” Deep breaths. “OK, got it.”

That wisp of fear threatened to freeze my upper-body mobility and make my legs tense and shake. I’ve experienced it before, on high points with drop-offs, with no clear path forward—that feeling of dread, that “I’m stuck … I can’t …” while legs pulsate like a sewing machine needle and my mind disassociates from the scene.

This time, thankfully, my mind focused instead of blanking out, and my body stayed responsive and strong. Perhaps it was the presence of my daughter there, and my desire to be a positive role model and not worry her (not one who freaks out and shouts F-bombs). Or perhaps it was feeling mildly pissed off that I—the most athletic of our trio—would have trouble passing over this rock that the other two could shimmy over without pause. In any case, I kept my shit together. I made some full-body moves—another reach, another step to a foothold I couldn’t see but had to trust was there—which enabled me to get up to the point to meet my daughter.

This boulder hung onto the mountainside of Wilson Peak, the 14er we gaze at from our house. If I lost my grip and slipped, I would slide and fall onto a pile of jagged rocks below, which wouldn’t be as bad as falling from the more exposed mountainside up above. But still, I’d likely break something.

At least a helmet protected my head—a bike helmet, because we only had two proper climbing helmets, which I let Morgan and Colly use. I took the bulkier bike helmet, which, combined with my prescription sports glasses that look like safety goggles, made me look like the rookie dork that I am, not a cool climber.

As I’ve mentioned in past posts, I’m not a climber. I’ve never taken lessons and never learned to use ropes and harnesses, except the two times a guide took us ice climbing. I’m a runner who occasionally gets to mountaintops that require scrambling.

But, I am proof that the more you do something, the more you adapt to it. My fear of heights has subsided, and the panicky sensation of vertigo from looking way down from up high hasn’t hit in recent memory. I have become more adept at Class 3 climbing (unroped climbing and scrambling that requires the use of hands to traverse a route). I have replaced the knee-jerk thoughts of “There’s no way I could do that” and, “I’m too old for that shit,” with, “I could handle that” and, “With age comes experience.”

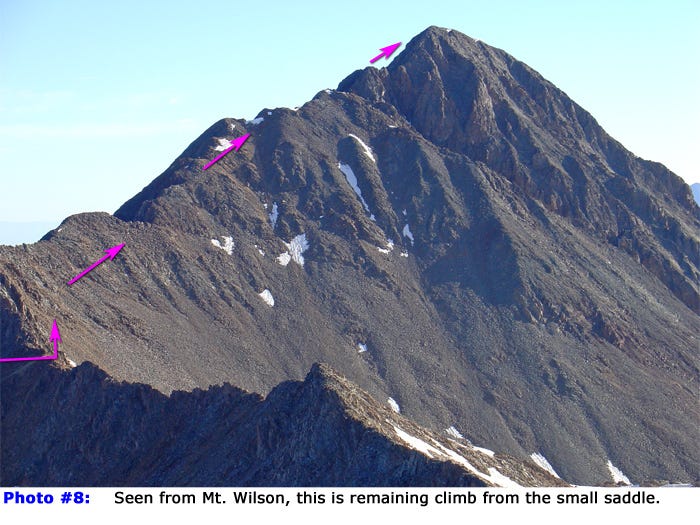

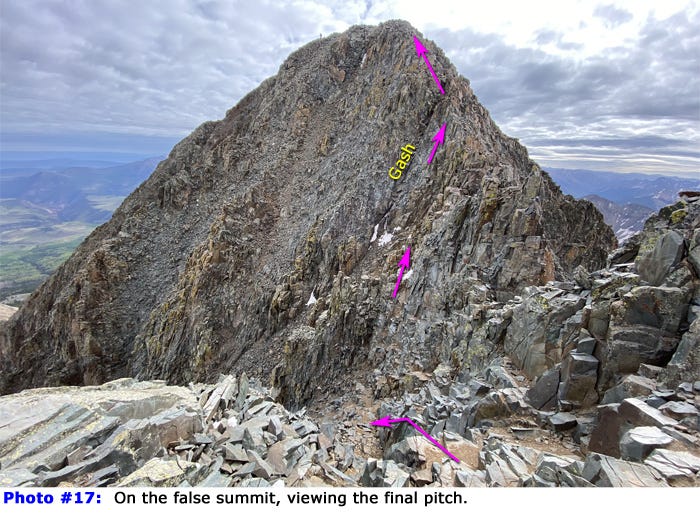

This rock traversing took place Saturday, at my daughter’s request, because she had never summited a 14er. I had been up Wilson Peak once before, a year ago (as detailed in this post), but that time, we had a guide. The guide had roped me in on the tricky crux to the summit, which last year at this time featured the added challenge of fresh snow on the rocks. This time, I was unguided and unroped—and thankfully, the summit still is in its late-summer snow-free state.

Throughout the day, I kept feeling gratitude and relief that we had done this once before with a guide. The prior experience with a guide gave us indispensable knowledge for navigating the route and handling the difficult spots. If you feel doubtful and intimidated by any first-time mountain adventure, then I highly recommend hiring a guide.

Wilson Peak is ranked 47th in difficulty out of Colorado’s 58 14ers. The entire mountaintop is a massive rock pile broken into bits from an endless cycle of freezing and thawing over millennia—rocks of all sizes, from jagged pieces that look like broken plates to boulders many times my body size—so to summit and descend this peak means hiking and crawling over rock, with barely a trail of crushed rock to guide the way. In the final quarter mile, the trail disappears, and the route becomes guesswork to pick the best line.

We made progress toward the summit in dicey weather. Wind blasted, rain sprinkled, but thankfully, we never heard thunder, and the rain did not turn to sleet or intensify. We put on every layer we brought to stay warm (and I cursed myself for wearing running gloves rather than grippy mountaineering gloves; they became wet and slippery, so I had to take them off and cope with cold hands). Near the final ascent, Morgan and I considered turning back, worried that once we got to the top, a cloud cover would reduce visibility to the point of making it difficult to see our way down, and/or precipitation might make the rocks slippery or even icy. But the sky cooperated enough, and we kept going upward.

As a reward, the precipitation produced multiple rainbows along the way.

(The video clip above shows a slice of the way to the summit.)

Summiting felt thrilling, but rushed. A cloud cover obscured the views and chilled us, so we had to limit our time to avoid getting dangerously cold. The clouds lifted enough that we could glimpse the green expanse of the mesa where we live, but not enough to pinpoint our house.

No matter. Colly was smiling, laughing, thrilled to be up top. But I wanted to get down before the weather turned truly nasty.

Getting down was nearly as slow, and at times more difficult, than the ascent, but we made progress. Other trail users passed us on their way to the top, and I felt pride bordering on smugness that we were the first up to the summit—along with two guys with whom we had buddied up and who took the photo of us at the top—by 9 a.m.

Believing that the hardest part (the crux and summit) were behind us, we grew a bit less focused on the way down where there is no clear route line, just a few cairns, and we accidentally chose a more difficult route back to the saddle where the scrambling begins, rather than following exactly the way we came. That’s where I nearly became stuck traversing a boulder in the scene described above, the only moment during the day when I felt my old fear. But we made it through and refocused on paying attention to route-finding and potential rock falls.

The sensations that stick with me about this 10-mile hike with a 14er are deep satisfaction, confidence, and joy, which came from skills developed over the past several years. Each time I get up to a ridge or peak and handle a technical passage with the aid of my hands, I get a little better at it and consequently feel better.

I’m welcoming and cultivating the ability to experience the mountains in different ways beyond running and hiking. True technical mountaineering with ropes to ascend hard-to-reach summits doesn’t appeal to me because of the danger and difficulty (although I’m fascinated by it and by my pioneering great-uncle, one of the greatest mountaineers a century ago). But trying new routes to get up high with Class 3 climbing does feel exciting and empowering.

Here’s Colly’s one-minute video highlight of our outing:

Five years ago, I seriously doubted I could ever handle these kinds of summits.

In the summer of 2018, I went to Ouray multiple times with my coaching client Tara for long training runs. I was training for the Ouray 100 and coaching her to complete the Ouray 50. The route involves extremely steep and challenging out-and-backs to tag peaks.

We made it up the Twin Peaks trail, where I had never been, and encountered rock outcroppings at the summit. We suspected the race director would make us get to the tippy-top of the rocks to officially tag the summit—he put hole punchers, each making a different shaped hole, at the summits, so race participants could punch their bib as proof they tagged the peak—so we decided we should practice getting up and down those boulders at the top.

I shimmied and scrambled up, a sense of dread and fear building in my chest, wanting to prove I could do it but feeling deeply uncomfortable and nervous. Finally, we sat at the top, but I didn’t want to look around to take in the views, which made me dizzy—I just wanted to get down. But how?

“I don’t know how I’m going to get off this,” I told Tara.

Thankfully, Tara has a background as a mountain guide. A role reversal ensued—my client became my coach. “Trust your feet,” she told me as she started down the rock, showing me how to glide and reach to find footholds. But I became frozen with helplessness—I lacked the trust and confidence in my body to make those moves. A spaciness began to cloud my mental clarity. I felts tears of fear and embarrassment fill my eyes, and I blurted out, “I suck at this. How the fuck am I going to get down?!”

She remained calm and guided me to follow her. My pride kicked in and helped—I didn’t want to fail as a coach. I thought to myself, If she can do it, so can I, and I forced myself to follow her. But I dreaded and hated every precarious moment descending those boulders, wanting nothing more than terra firma.

When we regained the trail, I felt shaky, mildly traumatized. I suck at this, I thought inwardly again. I couldn’t imagine ever wanting to do a climb like that to get to the top of a peak or being adept at it.

Now, five years later, I feel like a different person. I objectively can recall the size and difficulty of that scramble at the top of Ouray’s Twin Peaks trail and realize it’s not overly difficult or dangerous in terms of exposure. I’d like to go back and try again to prove it feels manageable.

This newfound confidence comes only because I’m hyper-focused and cautious, taking every precaution I know. Colorado 14ers—even the easiest, Handies—never become truly “easy” due to the vert, altitude, and potential for extreme weather. As the 14ers.com site puts it, “No 14er is ‘Easy,’ so when you hear this word when discussing 14ers, it simply means the peaks which are the least difficult to hike.” It’s dangerous to think of summiting any high peak as “easy,” because that feeling of (over)confidence leads to casualness and complacency, followed by accidents from carelessness or lack of preparation.

Tuesday, I found myself hanging off a rock wall with a 300-foot drop. And I felt fine. Hyper-focused and moving with meticulous precision, but fine, even happy.

I joined a small group of women from the Telluride Women’s Network on a guided traverse of Telluride’s Via Ferrata. I had done the via ferrata once before, in 2020, and wanted to prove to myself it wasn’t a fluke—that I could still tackle this intimidating cliff-hanging hike, and perhaps feel less scared this time.

Two summers ago, a woman fell to her death on this via ferrata. Our guide told us she and a friend were doing the via ferrata unguided. The woman senselessly unclipped from the cable and asked the other to take a photo of her standing on the cliff edge. Her friend looked away for a second to get her phone for a camera, and when she turned back, the woman was gone. Just like that, she fell. The image haunts me.

But that haunting—imagining the unimaginable of falling to death—is useful insofar as it converts fear into focus. I did the via ferrata methodically, zeroing in on the process of repeatedly clipping and unclipping to the cable (so that one of the two carabiners attached to my harness always was connected to the cable), grasping and moving from rung to rung, always maintaining a strong grip and a safety clip. This, in turn, gave me confidence to look around and enjoy the views, feeling awe more than fear.

Two of the women in our group—first-timers at the via ferrata—repeatedly expressed nerves and doubt on our hike to the cables. “I can’t believe we’re doing this,” one said. But they followed instructions and took it step by step, inch by inch, and discovered they could in fact do it.

Afterward, they kept saying, “I’m so proud of us!”

I’m proud of us, too.

Absolutely amazing. Spent my childhood hood in Colorado in the summers helping build houses. I had forgotten just how beautiful it is. Looks like it might be time to revisit. Best of luck on your race.

Hello! I stumbled on your blog because I signed up for the women's hardrock camp and am now panicking trying to read every course description, wondering if I'll be able to complete the group runs! Eeek! Can you point me to any resources? Have I made a mistake??? Will I survive??