The Weeklong Race That Changed My Life

When I turned 50, I found transcendence after five days of running in the desert

This week, I’m taking a real vacation, not the oxymoron of a “working vacation.” I’m with my husband and two horses on a special ranch in the San Luis Valley of south-central Colorado, spending most of the day in the saddle while taking an advanced horsemanship workshop. I’m therefore reprinting my favorite race report, because it spotlights an event that changed my life and that I hope inspires you to try something wild.

It’s the story of the 50th birthday present I gave myself, and how I ended up with the closest thing I’ll probably ever get to a lifetime achievement award.

If you’re a subscriber, thank you. If you upgrade your subscription to paid, you’ll get an invitation to a monthly online meetup and access to bonus posts.

In my 30s, I secretly wanted to be on the TV show Survivor. So a decade ago, when I was in my early 40s and the opportunity arose to participate in the 2012 inaugural Grand to Grand Ultra weeklong self-supported stage race, I said yes, even though I thought I might come close to dying from calorie depravation, heat stroke, or a snake bite.

I almost did get bitten by a snake in the middle of the night when, midway through a grueling 50-mile stage, I bent down to pick up what I thought was a headlamp dropped by another runner. Instead of being a headlamp strap, however, it actually was a coiled snake with a triangular head, its shiny eye reflecting my headlight’s beam. I jumped back and ran through the night on adrenaline, my mind mistaking every branch in the sandy path for another snake.

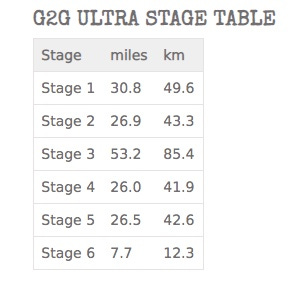

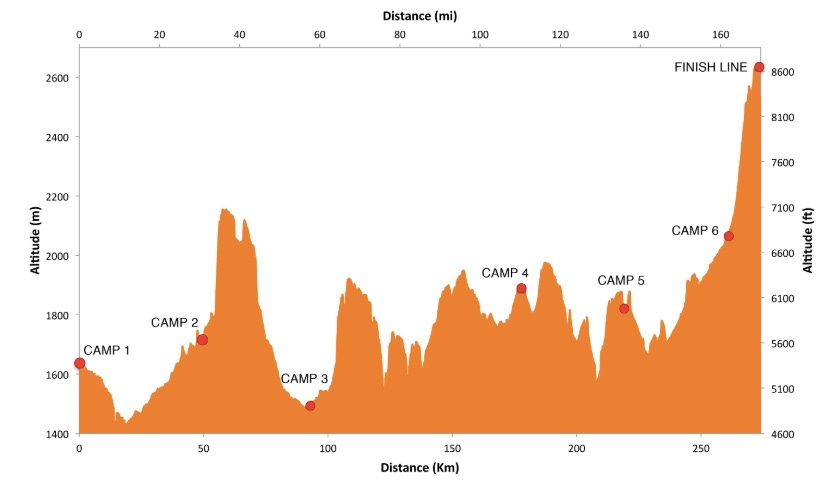

The race covers 170 remote, rugged miles from northern Arizona to southern Utah. It’s been included on several lists like this one naming the “toughest ultras in the world,” and it’s called the “Grand to Grand” because it goes from the Grand Canyon to the Grand Staircase. Competitors must carry all their food and gear for the week, and camp along the way. The event provides only water and communal tents.

I finished the 2012 event in 3rd place and repeated it in 2014 and 2019. The 2022 Grand to Grand Ultra starts September 18 after a two-year covid hiatus, and a large part of me really wishes I were participating again.

If this story motivates you to consider self-supported stage racing, feel free to contact me for training or gear advice. I also was interviewed for this podcast about how to prepare for this type of event.

Here’s the story of what went down in 2019:

I lay in my sleeping bag in the predawn hours of Friday, before Stage 5, shivering while my stomach growled audibly and abdomen muscles clenched. Cold seeped in through the bag’s ultralight layer and through my wool base layers and puffy down jacket. A rock, lodged in the hard earth under the tent’s ground cover, poked at my ribs because my minimalist sleeping pad had sprung a leak and deflated.

I was coping with insomnia in a brier-filled, ant-infested pasture somewhere outside of Kanab, Utah. During the day, we could see the coral and chalky-colored bluffs of Zion and Bryce national parks in the distance, so I knew I was getting close to reaching a finish line near Bryce’s towering hoodoos, overlooking the magnificent layer-caked landscape of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

Three men and three other women slept beside me in this square white canvas tent. We had shared the past five days and 136 miles as competitors in the Grand to Grand Ultra. Of the 102 runners representing 22 countries who started the event, 78 of us remained; we had one-and-a-half days, and only 34 miles, still to go.

One of the guys snored. But it was neither his noise, nor the cold and hunger, that kept me awake and shivering. It was anxiety, coupled with dread. It was the anticipation of snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

Jesus, I could really blow this, I thought.

At daybreak, I had to get up and try to run—to win—Stage 5 in this six-stage, weeklong self-supported race. It would be 26.5 miles of challenging terrain, in high heat at high altitude.

I intended to finish strong, as I had in the prior four stages. I had earned the place of first-place female against some other tough ladies. What I really wanted, however, was a spot in the top 10 overall because I felt strongly that a woman’s name should be listed among the top 10 finishers, for the sake of being a role model and encouraging other women to try this branch of ultrarunning. (About one-third of the Grand to Grand Ultra’s participants were female, and I was the only woman in top-10 territory.)

Suddenly, however, my top-10 spot was in jeopardy because of an unfortunate penalty earned after Stage 4. I felt like shit, physically and mentally. After four days of feeling nearly invincible, the past 12 or so hours had left me feeling depleted and decrepit, on the verge of a DNF.

Let me back up and explain why and what led to the whole penalty thing.

How Did I Get Here?

This story begins with me facing my 50th birthday and wanting to give myself a gift that would make me feel younger, stronger, and wilder.

I had competed in the Grand to Grand Ultra in 2012 and 2014, and its sister race the Mauna to Mauna Ultra in 2017. Each one of these weeklong, off-the-grid experiences—combining ultrarunning with camping—fulfilled and strengthened me in a way that’s hard to adequately articulate. It built my confidence to do things in my 40s that I might not otherwise have believed in myself enough to do, such as write a book, take a leadership position on a board, and build a house. I wanted to do it again in part to see how I would fare compared to when I last raced it at age 45 in 2014.

Mostly, I wanted a week to be alone with my thoughts, detached from devices, to contemplate how much my life has changed in the past five years and to figure out what I want to do in my 50s. It would be the gift of a retreat.

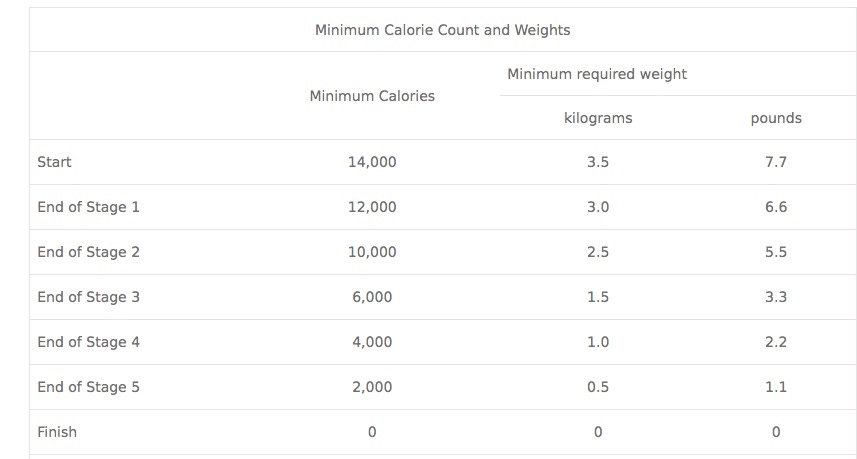

This year, I was determined to pack and eat smarter so that I could have as light of a pack as possible. (Competitors are responsible for carrying all their food and gear; the race provides only water, communal tents, and sunscreen and electrolyte tablets at checkpoints.) I got my food supply for the week close to the minimum requirement, to just over 14,000 calories. (If you want to know the details of what I carried, see this post.)

Stage 1: I set off with the other competitors from the north rim of the Grand Canyon and found my groove. I soaked in the views of the red-hued bluffs that make up the Vermillion Cliffs National Monument, and I felt proud that I had embarked on a fundraiser for the Conservation Lands Foundation that raised more than $10,000 to protect these national monuments and other BLM-managed public land.

I finished Stage 1 happy and relatively relaxed, not suffering the way others did on the stage’s final cacti-choked cross-country hill climb. I was 2nd female and 15th overall; a German woman age 28, Kathrin Atzor, had smoked Stage 1’s runnable hard-packed roads. She finished 24 minutes ahead of me. I didn’t care; all that mattered to me was that I had set a goal of running Stage 1 in 6:45, and I beat my goal by one minute!

Stage 2: My Colorado mountain-running legs and lungs did me proud on this stage. I started out in the middle of the pack, letting others blow their wad in the early miles through pastureland filled with more cacti, rocks, and other tripping hazards. I saw the race director Colin Geddes at the first checkpoint, and he looked puzzled because I was relatively far back, so I told him, “I’m being calm and careful.”

Then we hit the Navajo Trail, an old shepherding and Native American trail that climbs more than a thousand feet to the Kaibab plateau. The vegetation transitions from desert scrub to piñon and juniper forest. On that trail, I cut loose and powered ahead.

Pretty soon, I caught up to a young Australian woman with dark hair, Jacqui Bell, age 24. I didn’t know much about Jacqui, but I figured she must be hot shit because she has a sponsor that had paid for a filmmaker to follow her along the course all week for a documentary project. After the week’s race, I would discover that she has raced a half-dozen or so self-supported stage races around the world and is a top competitor. It began to dawn on me that she’d be the one to beat, more so than speedy Kathrin, because Jacqui has a wealth of stage-racing trail experience.

I bombed down from the Kaibab plateau and transitioned to hot, flat running on desert dirt. I found my grind gear, minimized walking breaks, sang more songs in my head, and passed a lot more people. I finished Stage 2 1st female, 7th overall; my goal that day had been to finish in 6:45, and I did it in 6:10, way faster than in 2012 and 2014! The overall standings for the first two stages combined placed me as 1st female, 8th overall. I had built an 11-minute lead over Kathrin, and a 1 hour, 9 minute lead over Jacqui.

But I knew that my lead could evaporate because anything can happen on the make-or-break Stage 3, the 53-mile long stage.

Stage 3: This stage is an extraordinarily hard 50-plus-miler because of the great variety of challenges it presents. It starts with a hard-packed runnable 6 miles, so you gotta go out relatively fast to bank time before the slower miles that follow. Then you climb 1000 feet straight up a vermillion bluff, then transition to sandy tracks through rolling desert hills framed by beautiful, bizarrely sculpted rock formations. Then you plunge into a hot, densely vegetated riverbed canyon, then climb an overgrown and rocky mountainside, then more rolling sandy tracks, until the halfway point that pops out at the Best Friends Animal Sanctuary outside of Kanab.

Then in the second half of the route, we faced the formidable Pink Corral Sand Dunes State Park, followed by a densely vegetated cross-country section that in past years I nicknamed Hell’s Garden, then more and more seemingly relentless deep-sand tracks.

While sitting around camp waiting to start, and realizing that the forecast called for hot temps that would feel even hotter in the full sun reflecting off the light-colored sand, I realized I would benefit from more calories than I budgeted for the long stage, since my body would be under more stress today. I therefore made a fateful decision to use an extra pack of GU Rocktane drink mix (250 calories) and a bag of potato chips (approx 140 cals) that were budgeted for later in the week. I transferred those rations to my snacks for the long stage, and sure enough, I was glad I had that mid-run fuel. But this seemingly innocuous decision would come back to haunt me.

I rocked the first 40 miles of the long stage. It’s kind of crazy how 40 miles in those conditions can feel so manageable. Clearly I was doing something right, because the day felt magical.

When the sun finally went down, I relished the 90 minutes of twilight when the heat of the day finally cooled off but we still had enough daylight to see.

At Checkpoint 6, mile 40, I left with my new friend Ilan Freiman who’s from Australia but lives in Hong Kong. We ran along the highway approaching the Pink Corral Sand Dunes State Park, and I felt in high spirits, eager to attack the two-dozen-plus sand hills that I had conquered in past years. They are insanely steep and soft. Ilan was under the misimpression that there’d be only a half dozen or so sand hills. I told him we’d face at least 20, probably more, and he seemed shocked. “Let’s count them!” I suggested, so we did.

The first one we could hike, but then we had to plunge our hands into the second one, which sloped like a ladder and rose at least two stories high. I punched my fists into the sand and started to bear crawl. Up up up we crawled on this wall of sand, briefly slipping backwards before regaining forward momentum, gasping for breath, finally reaching the top and pausing on hands and knees.

“That’s two!” I said. “How do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time!”

We slid down the backside of the dunes, strained our eyes to spot course markers in the distance, and progressively scrambled up each one. At one point, while bear-crawling, I placed my fist next to a tarantula as big as my hand. The creature seemed cool, and nothing could scare me.

The Milky Way on a moonless night illuminated a swath of the star-filled galaxy and made me feel supernatural. We counted 32 dunes. Eventually the dunes transitioned to a deep-sand track with mild hills. Then I followed the course markers to make a right turn off the track into the snarl of Hell’s Garden.

I don’t know the proper names of these desert plants, but imagine being surrounded at night by small trees and bushes with spike-covered branches. Mounds of dead wood and other rotten foliage mix with rocks and low-lying cacti to create an uneven, sharp footing. There is no such thing as a trail to follow. Occasionally, the ground gives way and drops 8 feet down a sandy bank into a gully wash, making for a scramble up the other side. At one point I tripped and almost face-planted into the carcass of a decaying sheep.

My dimming headlamp could barely catch the reflective glow of the pink course ribbons in the distance. Each ribbon is a lifeline; if you can’t spot the next marker, you’ll be entangled and disoriented until daybreak.

Suddenly, a shiny obstacle came into view: a tall barbed-wire fence that looked fairly new. All day we had passed through fences managed by ranchers and the BLM; when no gate presented itself, a helpful sign instructed us to climb over the fence, and a stump or some other obstacle aided the climb. But this fence had no gate, no sign, no stepladder—just razor-sharp wire about 5 feet high, attached to metal stakes that did not provide any footholds. The course markers clearly advanced on the other side of the barbed fence.

I looked around, disbelieving. Is this a joke, a trick? Finally I concluded we had to get through it, so I could choose to go over or under.

Not trusting my coordination to climb, and not wanting to shred my legs, I chose to go under. I took off my pack, threw it on the other side, and got flat on my belly to squeeze through the 18-inch-high gap between the ground and the first row of barbed wire. I found myself eye-to-eye with ants and beetles, and I felt sand on my cheek. I pondered internally, Who does this kind of shit at 1:30 in the morning? Then I roared out loud, “I DO!”

I got through the vegetation, I got through the final checkpoint. During the final three miles, I began to imagine the sand might be quicksand, grabbing my legs and holding me back, as if in a nightmare when you try to run but feel you’re struggling to swim.

Finally, around 2:40 a.m., I saw the white tents of camp and crossed Stage 3’s finish line. It took me 16 hours, 41 minutes. About half the competitors took 24 hours or longer to do the long stage, stopping to sleep and eat meals at checkpoints along the way. The race schedules two full days for Stage 3, so I could spend the second day (Wednesday) relaxing and recovering in anticipation of Stage 4.

After some sleep and daybreak, I felt satisfied and strong, but increasingly hungry. During the recovery day, I lay in my tent listening to a woman one tent over give away all her food because she had dropped out during the long stage and was heading home. I felt “hangry,” because it’s against the rules to give away food like that.

When someone that afternoon kindly offered me some of their food, I politely but firmly declined. “It’s against the rules, and I don’t want to jeopardize my spot,” I said. Hearing myself, I realized I had come to care a lot—perhaps too much—about winning.

Stage 4: Today was “only” 26 miles. I entered it in 7th place overall and 1st female with a comfortable lead.

I wanted to run strong today, so I ate some of my food budgeted for later that night at breakfast; for example, I used my hot cocoa pack to make a mocha with my instant coffee ration. Little did I know that this decision, coupled with the earlier decision to use some of Stage 6’s food on Stage 3’s long stage, would bite me.

I felt pretty good until the heat started reflecting off bright-white sand and my skin prickled in the sun. I reached the finish line of Stage 4 still feeling strong and confident.

Then my confidence evaporated, because race commissioner Garth Reader told me and everyone else as they crossed the finish, “Bag check. I need to see some mandatory equipment and weigh your food.”

I dumped out the contents of my pack. I had the knife, safety mirror, and emergency blanket he wanted to see. But when it came to measuring the weight of my food, I knew I was on thin ice.

“This is way too light,” Garth said. I pointed out that I had enough calories at the start, but he said that didn’t matter; I was short of the minimum required at the end of Stage 4. He referred to the chart printed in our race booklet:

The punishment: a one-hour time penalty.

I couldn’t believe it. The extra hour knocked me from 7th overall to 10th, and the guy in 11th could take me down. I pictured my family and friends, who were tracking the race results online, seeing my time from Stage 4 equalling 7:32 instead of 6:32 due to the penalty, and they would wonder why I had slowed down so much. I felt horrible.

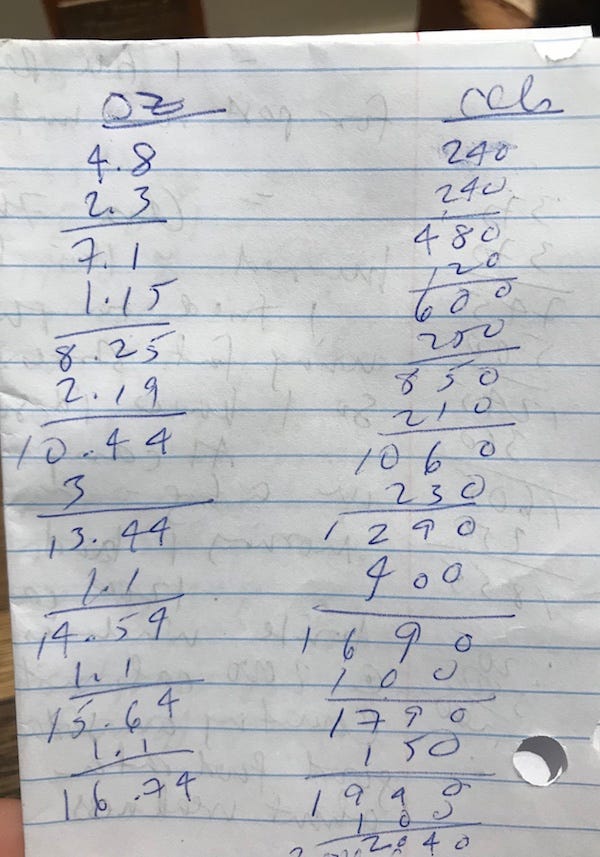

I went to my tent and took inventory of my measly supplies. I knew we faced at least a 50-50 chance that Garth would inspect us again after Stage 5, and I needed to have the required 2000 calories and 1.1 pounds of food after the next day’s challenging marathon-length run.

I frantically added up the remaining calories and ounces. The only way to make it work, I concluded, was to restrict myself to a tiny breakfast and minimal calories during Stage 5’s run so that I would have enough left over to pass inspection after Stage 5.

I solemnly nursed my allotted dehydrated-meal-in-a-bag and went to bed, which led to the nighttime scenario described in the opening: cold, hungry, wide-awake, and catastrophizing.

Given how depleted I felt, how the hell could I run a strong 26.5 miles for Stage 5 over rough terrain on only a 210-calorie oatmeal packet for breakfast, and then one 100-calorie GU gel and one 250-calorie GU Rocktane drink mix pack for the whole stage? The run might take up to 7 hours, and I’d have only 350 calories for the stage.

I lay in my too-thin sleeping bag, cursed my deflated sleeping pad, and visualized myself passing out and waking up on a medical cot with an IV in my arm, which would automatically disqualify me. I finally fell asleep for a couple of restless hours by telling myself, “Have faith that your body can do more than you think it can.”

I woke up with teeth chattering. I started to get dressed for Stage 5 and told my six stalwart tentmates, “You guys, I really need a pep talk today, because I don’t know if I can get through this stage without collapsing and DNF’ing.”

They rose to the occasion. Kevin exhorted me to believe in myself. Ultimately, however, it fell upon a woman named Michele to give me the kick in the pants I needed. I told her at the start line that I felt weak, hungry, and that I doubted I could run.

She looked at me disbelieving. “Think of the slaves and how they suffered,” she said. “As long as you have hydration and electrolytes, you’ll be fine. You could keep going for 40 days.”

Then she repeated, “You’ll be fine.”

That was precisely what I needed to hear. I would suffer, but I would be fine. I could do this.

Finding Transcendence in the Final Stages

Stage 5: I took off running in a sandy track with the others toward this stage’s highlight: Peekaboo Slot Canyon. Crimson-hued rock walls, tall and curvy and streaked with blond highlights, rose up on both sides, and the rocky riverbed began to narrow to a thinner ribbon of a trail. The more the trail narrowed, and the taller the rock walls became, the more anxious and claustrophobic I felt. I repeated a mantra, “Calm The Fuck Down.”

I navigated the ladders we had to descend in the canyon’s steepest drop-offs, I scooched over big boulders, and I emerged from the canyon feeling pretty OK.

I had one bottle full of the GU Rocktane drink mix, and one GU gel in my pocket. I vowed to save the gel until after four hours. I wondered how long I could nurse the 250-calorie bottle of sports drink. I took a sip, swished it around my mouth and swallowed. I decided to have a sip no more frequently than every 20 minutes, so that it would be like a slow glucose drip.

The heat beat down. I kept running the sandy tracks. I got the songs Staying Alive and Running on Empty stuck in my head.

Finally, gratefully, I caught up to Jacqui and felt almost giddy with happiness for her company. Looking at her, I tried to remember what I was like at her age, 24, when I started running in early 1994 a couple of months before my 25th birthday. Would she still be doing this a quarter-century from now, like me? Would I, at 75? I hoped so.

In the second half of the stage, the course diverted from the sandy track to a cross-country section introduced this year. Given that the Grand to Grand seems to strive to make the route as difficult as possible, I should have known it’d be tough. Sure enough, these three or so miles seemed like a daytime version of Stage 3’s Hell’s Garden, except it also featured a scramble up a steep hillside covered with desert scrub—a climb that I later heard made some people sit and cry. I scrambled up it and followed the route to its final six or so miles of runnable hard-packed dirt and gravel.

I took one of the final sips of the remaining sports drink. Amazingly, I felt no hunger. I felt no pain. I felt fine. I felt—it hit me—transcendent.

We ultrarunners like to talk about “transcendence,” but I don’t think I had ever really experienced it before now. Here, I transcended doubt, discomfort, emptiness. By giving this race everything I had, I reached a state of flow and fulfillment.

I stepped over a three-foot-long stretched-out snake in the roadway and barely cared. I took a swig of plain water and spit it into my buff to cool off my neck in the full-strength sun. Then I tore open and swallowed my single 100-calorie GU gel. I was going to finish this thing as fast as my body would allow.

I caught and passed a British man named Simon, who was vying for 11th place overall. As the white tents of camp started to come into view, I looked over my shoulder to see how far behind Simon was. But the person behind me didn’t look like Simon. It appeared to be Kathrin. Her roadie legs were eating up these final runnable miles, and she wanted to catch me before she ran out of real estate. Not today.

I ran that final mile as if finishing the Boston Marathon. I reached camp in 6:35, first female and a minute-and-a-half in front of Kathrin. In the overall standings, I still held onto 10th place, with a 55-minute lead over 11th-place Simon.

When I asked Garth if he was going to inspect my bag again, he said, “No, don’t worry; go ahead and eat whatever you have.” I gleefully ate and drank the calories that I would have used during the run—a Stroopwafel, another packet of Rocktane drink mix, and then my recovery drink mix.

Michele predicted that I would be fine, but I felt fantastic.

Stage 6: Only 7.7 miles of trail stretched between the final camp and the finish line. We woke up knowing we’d be done by noon. We all got dressed and ate breakfast with a touch of melancholy because this would be our last morning together.

Located at 6700 feet elevation, the final camp was downright chilly on the overcast autumn morning. I put my long-sleeve wool base layer on under my race shirt. The route would climb 2000 feet on forest road and single-track trail, through the Dixie National Forest hugging Bryce National Park.

The race director divided the competitors into three staggered starting waves, the fastest group starting latest, so that we would all arrive at the finish line within the same window of time. I therefore got to linger at camp, wrapped in my down puffy and emergency space blanket for warmth, and savor the company of the frontrunner guys whom I’d come to know and like.

At last we took off. Kathrin was the only other woman assigned to this final starting wave. I knew I didn’t need to run hard—my place was secure, I could walk it in—but in the cold air, with the excitement of reaching the finish, I felt frisky.

As we began ascending a forested mountainside ablaze with golden aspens, my emotions started to bubble to the surface. I felt gratitude and love for my body—a self-compassion that I rarely experience. This back, which three months earlier had been in such pain from a fractured vertebra and strained muscles, had carried my pack for a week. These legs, whose hamstrings usually stiffen and ache, had transported me with nary a complaint for 170 miles.

When the lumpy, crimson-colored rock spires called hoodoos came into view, the route turned onto the aptly named Grand View Trail. We were approaching a summit that overlooked the pink cliffs of the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument.

I increased my pace on the singletrack and reflected on a question that had prompted me to give myself the gift of this “retreat”: What am I going to do in my 50s? This, I realized. This is what I do, who I am, where I find friends. This is my thing. It’s not my only thing, but it drives and improves every other thing that I do. You do something long enough, you eventually get good at it. Simple as that.

I came around a corner and saw a throng of competitors and volunteers cheering, and I heard the words “2019 Grand to Grand Ultra women’s champion” on the loudspeaker.

Overall, I won the women’s race and came in 10th place with the men, with a cumulative time of 45 hours, 34 minutes (which includes the one-hour penalty). Jacqui finished 2nd woman and 14th overall in 48:30. Joseph Taylor of Salt Lake City won the men’s race in a blazing 34:16.

I embraced the race directors, Tess and Colin Geddes, and thanked them for creating an event that has changed my life

Thank you for reading such a long post, and best of luck to the 2022 participants! I’ll be back next Wednesday with a fresh post related to Colorado mountain running and living.

It is a great story! I was in a hurry so jumped ahead to see what happened! Very exciting (and brave!)

well done Sarah again -the ultimate inspiration for runners at all ages - congrats :)