The Trail Race That Changed My Life

A blast from the past that illustrates the differences between road and trail racing

This post is coming to you late in the day, rather than in the morning as usual, because I tested positive for covid this morning and have significant symptoms including fever, runny nose, aches, and chills. And brain fog, for sure. I’m operating at half speed.

I felt good and healthy yesterday, and ran five strong trail miles with some plyometrics at the end. I felt tired but attributed the fatigue to a lack of sleep last weekend as I paced/crewed and then volunteered at the Hardrock Hundred. By bedtime, I had a tickle in my throat. I slept restlessly and lightly, and by this morning, I had full-blown cold symptoms.

I’m fairly certain I picked up the virus while in Silverton Wednesday through Sunday, in part because my defenses were down from lack of sleep. I spent early Friday night pacing Yitka Winn for a segment (Ouray to Animus Forks) until close to midnight, then barely slept because I was so jazzed from the experience and excited to follow her and other competitors online. Then, Saturday night, I worked an eight-hour shift from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. preparing and serving food for all finishers and their pacers who took 40 to 48 hours to finish. Pulling that all-nighter wore me out and put me into close proximity with scores of people indoors.

I invite you to click through to my Instagram post that has ten photos and a caption summarizing last weekend:

For today’s post, I intended to narrate the PowerPoint slides of a history talk I gave last Wednesday, about the mining towns and some of the characters along the Hardrock route, because several people said they were sorry they missed my talk. I’m gratified the presentation was well received by a full room. But now my voice is too croaky to narrate well, so I will save that for next week.

For this post, I have a blast from the past. It’s inspired by a conversation yesterday with my running buddy Leslie. We got to talking about the East Bay Area suburbs, where I used to work when I got out of grad school, and I explained that I first ran trails around the foothills of a big mountain near Walnut Creek called Mount Diablo. She was curious about my transition to trail running.

Then it hit me: I should share that story, because it illustrates not only the differences between road and trail running, but also how the sport looked back in the “old school” days of the mid-2000s. Plus, it features a cameo by Scott Jurek!

It’s also helpful for me to re-read this experience from nearly 20 years ago, because it reconnects me with the beginner’s mindset of wonder, curiosity, and innocence that I felt when I first got involved with this sport. I want to nurture that mindset to fully appreciate and revel in the ultras I have on calendar, rather than approaching them with preconceived notions of how they “should” unfold and how I “should” perform.

What follows is an excerpt from the introduction of my 2017 book, The Trail Runner’s Companion: A Step-by-Step Guide to Trail Running and Racing, from 5Ks to Ultras. It tells the story of my first trail marathon in 2005, which took place on Mount Diablo. It was my tenth marathon ever, the prior nine being paved road races. In the 19 years since then, I have run 112 more marathons and ultras (if you want to see my list, it’s here).

I was in my mid-thirties, and my kids were 7 and 4, when I attempted my first trail marathon. Here’s how it went and how it opened my eyes to the differences between road racing and trail racing. It captured my heart and put me on a path to being the ultrarunner I am now.

A starting-line scene like no other

In 2005, one month before I turned 36, I lined up for a marathon unlike anything I’d ever experienced, with runners unlike any I’d ever met.

My prior road-racing experience made me familiar with the crush of bodies standing in starting corrals in big-city races. I’d felt the stress and thrill of ticking off 6:20 miles to get under 40 minutes at a 10K, and I’d been working on breaking 3:10 at the marathon because I wanted to “BQ like a man”—that is, qualify for the Boston Marathon under the men’s standards for my age group.

This marathon, however, featured no starting corrals or pacing groups, no long lines, no purple Team In Training singlets, no rock bands, no balloon arches, and no earnest-looking runners doing strides to warm up for a fast start.

Instead, I encountered fewer than 150 people in an oak grove off a dirt road at the base of Mount Diablo, a double-peaked mountain that rises some 3000 feet from its base and offers escape from the suburban sprawl about 30 miles east of San Francisco.

These runners stood around looking relaxed and checking out each other’s gear while asking about friends, family, and recent or upcoming races. Several said hi to me, even if I didn’t know them.

Many wore bandanas around their necks—for wiping off sweat and getting wet to cool off—and fabric coverings over their shoe openings for keeping out dirt and pebbles. One bearded guy wore threadbare denim cutoffs and carried two water bottles with handles made from duct tape.

I looked at my single 20-ounce hand-held water bottle with a tiny pocket that contained only two energy gels. Did I have enough water? Calories?

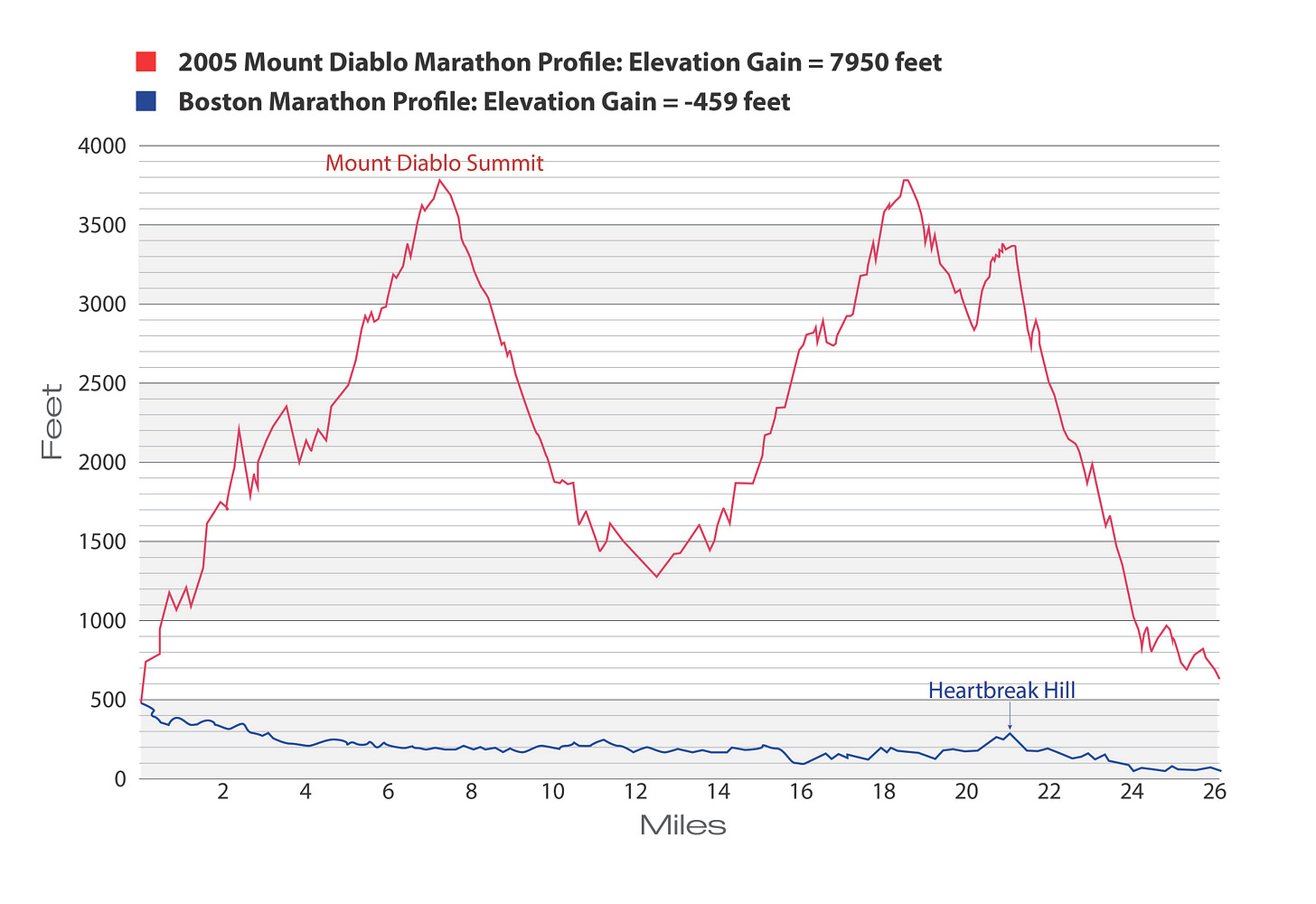

Accustomed to water stops every two to three miles in races—races that never lasted longer than about three and a half hours—I didn’t give much thought to carrying water or food. But the day was warming up, and the first five miles up switchbacks looked like a tall wall on the course elevation profile.

A man with a bullhorn called people over to an open gate, which would serve as the makeshift starting line. He asked the group, “How many of you are doing the marathon?”

About one-third of us raised our hands, which generated polite applause.

“And how many of you are doing the 50-miler?”

A much louder cheer went up. Suddenly being in the marathon felt like being in the kiddie pool—and I wanted to get good enough to dive in and swim with the big kids!

I wondered if I should move toward the back, but then I realized the marathoners and ultrarunners mingled together, no one elbowing to get near the start. I also noticed that several runners deferentially wanted to get behind one person in particular—a tall guy with curly hair and a headband who stood just a few feet from me, who was smiling and gesturing for others to get up in front with him.

“No way,” said one, backing off from the quasi-celebrity, “if I try to hang with The Jerker, I’ll die!”

At that point, I realized I was starting a race with the country’s top male ultrarunner, Scott Jurek, the six-time winner and record-holder of the Western States 100-mile Endurance Run. It turns out it’s typical at races like these for the so-called “elites” to hang out and start with the mid- and back-of-the-packers, given the “we’re all in this together” vibe of trail racing. Jurek was out there to complete the 50-miler as a mere training run. (Two months later, he’d go on to win his seventh consecutive and final Western States 100.)

The race director briefly explained the course markers that we were supposed to follow, but I failed to pay attention because I was so in awe of being in the presence of Scott Jurek and so disoriented by the unceremonious race start.

Without warning or fanfare, the director counted down from 10 to 1 and said, “Go!”

We all started running comfortably, many around me continuing their conversations. It felt more like a casual group run than a race. Should I go faster? Should I slow down? What was I doing running in plain view of Scott Jurek’s heels?

I had no idea how my first trail marathon would unfold, nor did I realize I was starting to follow a branch of the sport that would become my life’s passion.

“Sometimes you feel like a nut…”

The dirt fire road, bordered by manzanita and oak-bay woodlands, steadily climbed, and the runners around me downshifted to a hike. I copied them, swinging my arms and trying to match their pace. Instead of feeling guilty about walking, I realized that hiking in a race like this was the smartest, most efficient thing to do—and it felt good! It stretched out my calf muscles and Achilles tendons, and it kept my heart rate in a sustainable zone.

I stopped caring about the fact that my pace averaged only around 14 minutes per mile on the uphill. I felt liberated from my watch while running more by feel than by time, and I savored this powerful lower gear.

Some five or six miles up the mountain, we came to the first aid station. A folding table covered with sweet and salty snacks, and liters of Coke and ginger ale, greeted us, staffed by a couple of volunteers who helped runners refill their water bottles. Everyone took time to chat, crack jokes, and thank the volunteers. No one rushed through, grabbed a cup and threw it on the ground.

Feeling hungry, thirsty, and hot, I savored the buffet of goodies and let my cravings be my guide of what to eat. My eyes focused on a paper plate of cut-up PayDay candy bars. I never eat junk like that. But the gooey mix of peanuts and caramel seemed to speak to me, igniting a primal urge. I grabbed a chunk of PayDay, wolfed it down, took some swigs of Coke, refilled my water bottle and thanked the volunteers.

The PayDay bar lived up to its name, because five minutes later, I felt like a million bucks. Cruising on a ridgetop fire road, I took in the view of wind-swept grasses that covered rolling hillsides, which spread out toward the cityscapes and, all the way on the horizon, to the blue of the San Francisco Bay. The scenery, mixed with the sugar intake and endorphin rush, made me feel literally and figuratively high, as if I were soaring toward the summit like one of the hawks that circled the peaks.

The trail snaked upward past jagged rock outcroppings, so once again I downshifted to hiking. I was unsure of how many miles I had covered, or what my pace measured or where I was in relation to the other marathoners—but I didn’t care. Instead, I experienced a mix of feelings that I couldn’t recall in any recent road marathon: Joy. Wonderment. Excitement. Discovery!

I spotted the radio towers marking the summit. So close, and yet so far! Just getting to the top felt like a victory, even if I were only halfway through the race. I transitioned between hiking and running, moving as efficiently as possible. Steadiness mattered more than speed.

Popping out at the parking lot of the summit, my water bottle empty again, I hungrily greeted a couple of guys manning the aid station and thrust my grubby fist toward another pile of PayDay bars. I felt like a grizzly bear that emerges from hibernation with pent-up energy and a voracious appetite.

“Hey,” said one of the guys, “first woman up!”

I stopped my double-fisted food shoveling and Coke swigging to sputter, “No way! Are you joking?”

“Yeah. A couple of the guys in the marathon and 50 went through, but you’re the first woman we’ve seen.”

Gulp. I felt a twinge of competitive pressure, as if I should drop everything and run to keep the lead. I had felt free from such pressure on the climb to the summit, when it was just me versus the mountain, and I didn’t want to experience that pressure on this day. I wanted to keep having fun. So I deliberately lingered a little longer to talk with those guys and admire the summit’s views. I felt on top of the world and looked forward to flying down Diablo. Thanking the guys, I ran off with a handful of trail mix to top off my tank.

The trail’s footing turned to loose rock, which my shoes slipped and scuttled over. Going down was harder than it looked from afar. In some places, the trail became so narrow and overgrown with scratchy brush that I couldn’t see my feet. I just had to plow through the clawing branches and take extra care not to catch a toe and trip.

Exhaustion mixed with elation, along with being solo on this relentless trail, made me feel increasingly loopy. With no one around to hear, I burst out singing the commercial jingle from childhood that got stuck on repeat in my head when I ate the candy bar at the aid station: “Sometimes you feel like a nut, sometimes you don’t! Almond Joy’s got nuts, Mounds don’t …”

As the downhill became progressively steep and challenging, I put a lid on the silly song and became single-mindedly focused on not falling. Never had I tried to run down something so rugged. My running became a cautious hike as I leaned back and eased down rocky chutes that seemed as steep and slippery as a playground slide, grabbing branches to steady myself.

Suddenly something flew into the corners of both eyes and landed on my tongue. Rapidly blinking and gagging, I saw a small cloud of tiny black dots in front of my face, and then I felt those black dots all over my eyes, ears, arms and legs. Gnats!

A disgusting swarm of these miniature flies blindsided me with a sneak attack. I stopped completely and ridiculously waved my arms, spat, rubbed my eyes and stripped off my shirt. Then, shot full of adrenaline, I took off running with a fearlessness on the downhill that I lacked before. I heard myself singing again, “Sometimes you feel like a nut…”

The midday sun beat down, and I put my shirt back on for protection. I drained my bottle. I lost track of miles and, for the first time in a while, looked at my watch. It showed that I had been going for over four hours. Four hours?! That’s longer than my slowest-ever marathon, and I doubted I was even near Mile 20.

A sound in the bushes on the hillside above my head made me look up. I half expected to see a deer bounding, as I had seen earlier in the day, but instead I glimpsed long, brown hair flowing and outstretched arms windmilling through the air. It was a woman gracefully galloping down the mountain, running over the rocks as smoothly as water flows downstream. Her numbered bib indicated she, too, was in the marathon.

I moved to the side to let her pass. “Good job!” I said with genuine admiration.

“Thanks!” she said, beaming.

I had just lost the first-place position, but watching this younger, more skilled woman’s grace and gutsiness, I felt more inspired than disappointed. I resolved to try to keep her in sight and to copy her style, as if she were my guide more than my competition. I wanted to emulate her intrepidness and smoothness.

An hour later, we reached the flatter miles on the foothills toward the finish line. I lost sight of the lead woman. I lost track of time. All I could muster was a slow jog in granny gear as my skin crisped in the sun and my mouth became parched.

Five hours had passed—much longer, in terms of time, than I had ever run before. Not knowing where the finish line would be or how far I had left to go, I made myself pick a point in the distance and commit to run to that point without stopping or walking.

“Just make it to that tree … just make it to that course ribbon,” I told myself. “You have to finish … you WILL finish.”

I fantasized about lying down and guzzling cold drinks at the finish line. I was no longer racing; I was persevering. I was struggling to survive the most challenging marathon of my life. To finish would be to win, regardless of my place.

Finally, in the distance, I spotted the curve in the canyon and the grove of oaks where we started the race that morning, which seemed like eons ago.

Speeding up and feeling relieved, another feeling kindled in my chest and head: that of pride. I had gone all the way up to the summit and all the way back down, for the first time ever and as hard and as fast as I could! No mere marathon, this had been a test of mental and physical fortitude far more challenging, dramatic, and adventurous than I anticipated.

With no one around to watch, I sprinted past the trees and bushes in the final stretch and felt more heroic than when I ran past throngs in the final mile of Boston. I burst over the finish line with a grand total of about a dozen people watching—the handful of guys who’d finished the marathon, the woman who beat me, the race director, and some volunteers. They applauded and greeted me as if I were a star. The race director hugged me. I high-fived the first-place woman and told her I thought she was amazing.

A communal picnic ensued. A cooler full of beer beckoned. I could get used to this, I thought, feeling profoundly satisfied from the hard effort and the camaraderie. But doing the 50-miler? That’s truly insane!

When I crossed the finish line, the clock read 5:23. Two hours slower than my typical marathon. But in many ways, it was my best marathon time to date.

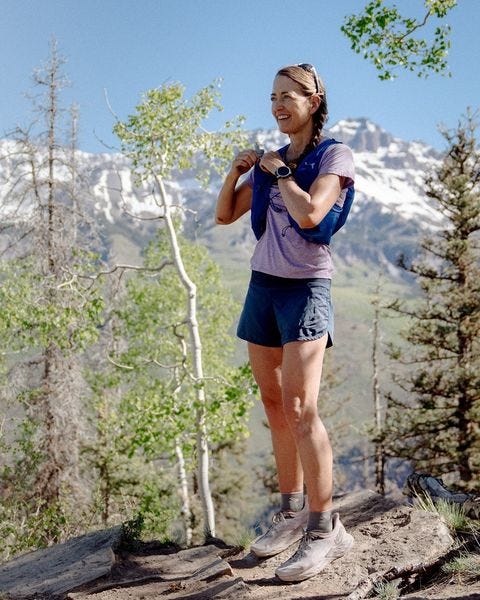

The above photo was taken in May when a photographer for AARP asked if they could spotlight me on their Instagram. It seems they’re trying to rebrand for GenX and show older people doing active and interesting things. I thought, sure, why not? I’m happy to encourage older people to hit the trail. This is how it turned out with a mini-profile in the captions.

Did you have a first trail race that affected you profoundly? Please describe in the comments below!

Wow, ultra running sounds like my kind of sport! Have to come back for another lifetime. May your illness pass quickly and completely. I really enjoyed participating in your group chat yesterday.

Polly

What a great story! I had a similar love affair with the trail community after road running for a few years. Wondering if you still like paydays????