The Must-Read Western States Endurance Run History

Plus, advice for avoiding and surviving a lightning storm

Hello, summer solstice! I’ve been waiting for summer, and now it’s here with a short-term forecast in my region of blissfully boring blue-sky weather. I have two summer-oriented stories for you, the first based in California. It’s a story—the story—of the Western States Endurance Run. Then, for all of you who spend time in the high country—especially here in the high-altitude, extreme-weather San Juan Mountains—a story about lightning safety.

Thursday, I fly to Northern California for what some call “Statesmas,” a series of days around the 100-mile Western States Endurance Run so special and anticipated that it feels like Christmas in summer.

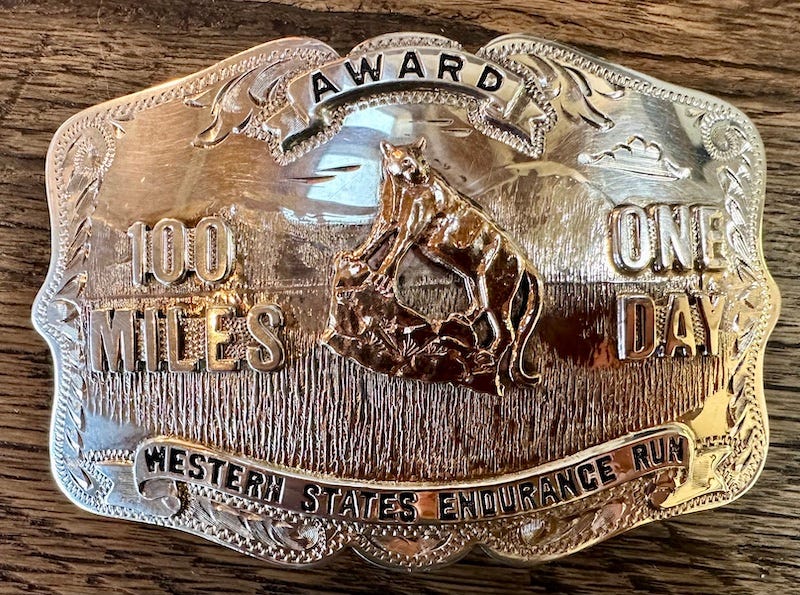

I’ll spend Friday around Olympic Valley, reconnecting with old ultrarunning friends and participating in a fun run up the ~2500 foot climb known as the Escarpment that Western States runners face in the first four miles. Then Saturday through Sunday morning, I’ll crew and pace my friend Soon-Chul Choi, who’s running States for the first time after several years of trying to gain entrance through the lottery. I’ll run the portion from Foresthill to the river with him (miles 62 - 78 on the course). Best of all, I’ll spend Sunday morning at the track at Placer High School in Auburn, cheering on him and all the runners who must finish within 29:59:59 (10:59 a.m. Sunday Pacific time) to earn a buckle and an official finish.

I’ve been following this event—the world’s oldest 100-mile trail race—since the mid-1990s, and I finally got the opportunity to run it in 2016, in a time of 23:44. Western States stands as the best, most special 100-mile experience of my life. It lived up to the hoopla and hype.

But, how can I—how could anyone—adequately capture the essence of this event and its storied history? Like the Boston Marathon or Hardrock 100, you have to be there in person and learn the lore to grasp the powerful spirit and multifaceted aspects that elevate the run from a mere single-day athletic event to a heroic saga and tradition.

Thankfully, someone—the best person I know to write the story—has written the Western States Endurance Run’s 50 years of history in the most compelling way I’ve read yet, better than any of the many one-off documentaries or articles about the race.

I spent the last three days devouring a new book, Second Sunrise: Five Decades of History at the Western States Endurance Run, by John Trent. It’s a gem, with John’s writing flowing around a spectacular collection of photos and memorabilia. I highly recommend it. Limited copies are available now for its Kickstarter backers and for sale this weekend at States; you can pre-order it here and learn about its Kickstarter campaign here.

John Trent is a longtime sportswriter and race director from Nevada who became involved with the Western States Endurance Run in 1987, when he covered it as a reporter. He then went on to run it 11 times and to serve on its board starting in 2004, for a time its president. I’ve known and followed him since I got involved with ultras and have found him consistently positive and encouraging to runners and writers like me. To hear him talk about the history of States and his experiences running it, you can listen to this UltraRunnerPodcast interview I did with him in 2015 (which is fun to hear for perspective on some of the ways the sport has changed and stayed the same over the past eight years).

There’s so much to love about this book, but the chapters devoted to the early history, from the late 1970s through the mid-1990s, really moved me. Most of us have heard Western States’ origin story—at least, the part about Gordy Ansleigh first covering the Tevis Cup’s route on foot rather than horseback. And most of us know about Ann Trason, Tim Twietmeyer, and Scott Jurek, who dominated the run and brought international interest in ultrarunning during the 1990s through early 2000s, transitioning to the modern era of the sport. This book does justice and gives credit to all the trailblazing characters in between, from the late ‘70s through 1980s, who established and nurtured Western States as a separate event from the Tevis Cup equestrian endurance ride, and who figured out and advanced ultrarunning when they had few role models.

The book pays homage in particular to a dynamic duo of women, Mo Livermore and Shannon Weil, who developed the vision and handled much of the heavy lifting to establish and promote the event in the early years, serving as its co-race directors. (Mo continues to serve on the WSER board and is a special role model for me; I got to know her more than 20 years ago through a family connection, and she introduced me to the sport of ride and tie. Check out this Trail Runner article for my Q&A with her about Western States’ early days.)

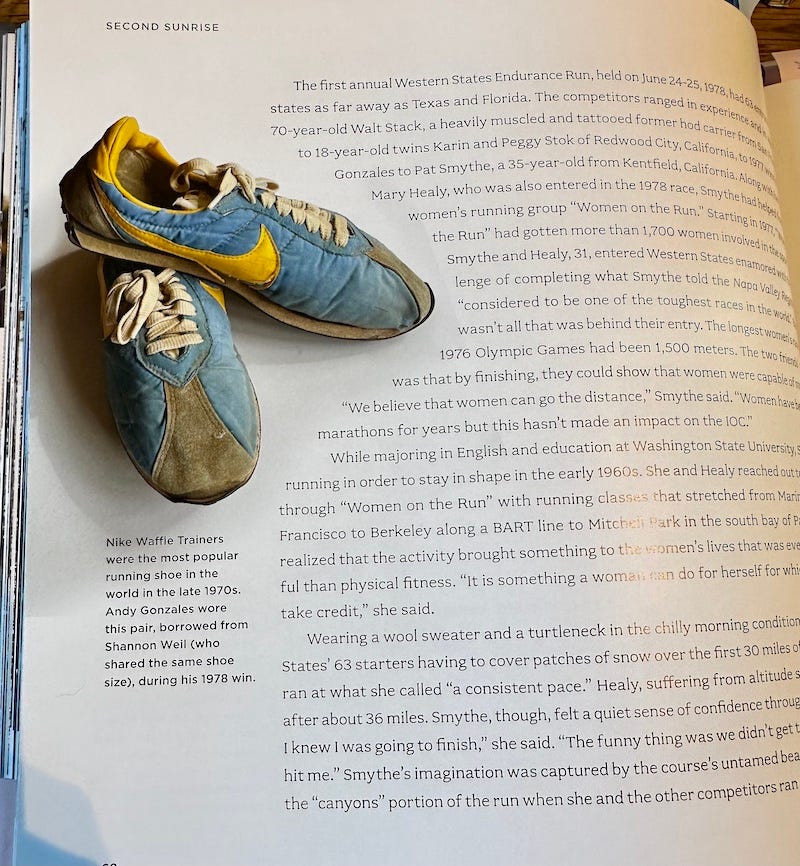

Reading Second Sunrise, I learned about amazing runners and thought to myself, “Why have I not heard of this person before?!” For example, in the pivotal year of 1977—the first time Western States was held as a runner’s race, rather than a subcategory of the Tevis horse race—Andy Gonzales, 22, won with a then-unthinkable time of 22:57. The next year, he lowered it to 18:50. Gonzales comes across as an ultra version of Prefontaine and a prototype of Anton Krupicka.

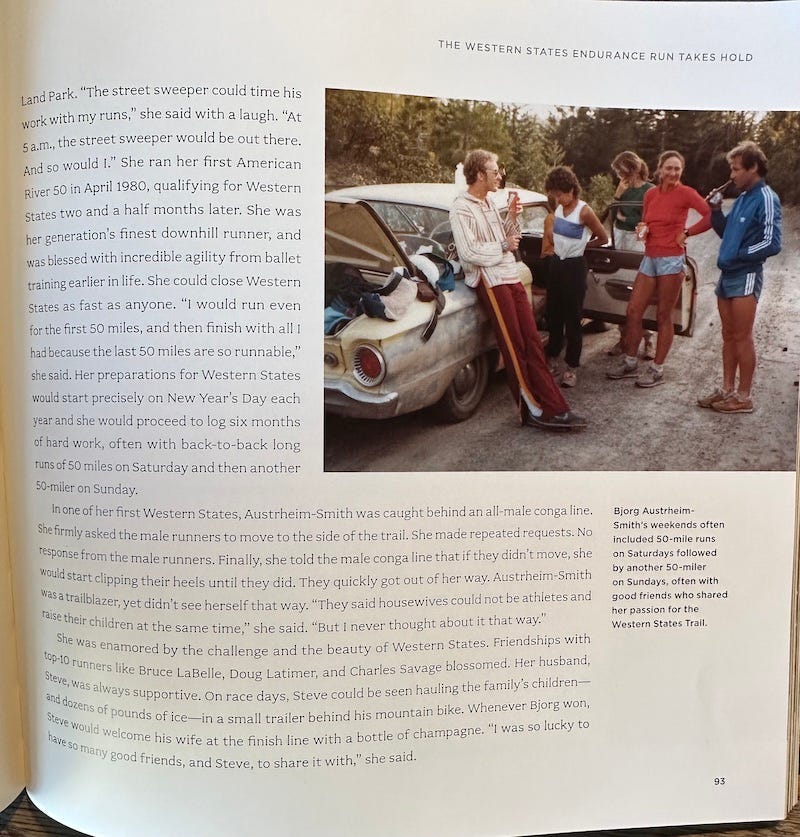

Additionally, we learn of several pioneering female ultrarunners who accomplished incredible times in the years before women were allowed to run the marathon in the Olympics. Skip Swannack became Western States’ first female sub-24-hour finisher in 1979. Then Bjorg Austrheim-Smith, a mother of three, won Western States three times from 1981-83 while in her late 30s, showing that mothers with young kids also can fit ultrarunning into their lives. “They said housewives could not be athletes and raise their children at the same time,” she says on page 93, “but I never thought about it that way.”

In the later chapters, John shows how Western States is so much more than a 100-mile race. It also developed into a massive collective effort to maintain the Western States Trail, as well as a leader in sports science research. He captures the challenges that current race director Craig Thornley has faced since taking the helm a decade ago—from fires to policies to the pandemic—and how Thornley’s and others’ love for the trail and the event keeps them going. (I also profiled Craig Thornley for iRunFar here; check it out to learn more about Western States’ present and future.)

And finally, in one of my favorite passages, John tells the story behind 70-year-old Gunhild Swanson’s historic finish in 2015. You can watch this video below to feel the thrills of the Golden Hour, but the details in Second Sunrise set the scene to capture the full drama. “You’ve got to love a sport where the most exciting thing that happened all year was a last-place finish by a 70-year-old grandmother,” Karl Hoagland tells John Medinger.

Folks, order the book and read it—it’s worth it!

For another blast from the past, I invite you to read this profile of Ann Trason, the unparalleled 14-time Western States champ, that I wrote way back in 1997 when I was a rookie runner. It was through living in her neighborhood, seeing her run, and learning about her career that I first got interested in the Western States Endurance Run.

Best wishes to a member of this subscriber group, Angie Woolman, who’s running her first States and who at 69 will be this year’s oldest female competitor. I can’t wait to see Angie have the run of her life!

Last weekend, before this mild weather pattern settled in, much of Colorado received a final winter-like punch. Hail pounded our roof and made the yard look snowy. Thunder rattled our walls, and forked lightning touched down on the hillsides right outside my window.

On Saturday, I ventured up and over Ophir Pass at 11,700 feet, scrambling over snow and talus fields because the old mining road is still blocked from snow. Thick slate-gray clouds gathered, the temperature dropped, and I grew increasingly nervous about a thunderstorm.

I had planned to run the Silverton side of the pass down the the highway and then turn around for a double crossing of the summit. But a half mile after summiting and descending the back side toward Silverton, my judgment and gut told me to turn back early and to finish my run at a lower elevation. I didn’t want to put myself in danger by being exposed above tree line if and when the sky opened and discharged electricity.

While in the mountains with a planned route in mind, or while running mid-race in a mountainous ultra, it’s difficult to alter plans for the sake of weather and safety. It’s also not an easy call. Can you time your pace and distance to “beat” the storm—sometimes necessarily running toward it to descend to a safer location—or will you put yourself smack in the middle of the most dangerous conditions? That’s the question I asked myself while “reading” the clouds.

A few factors reassured me. The atmosphere felt relatively peaceful due to lack of wind, telling me this was not a fast-moving storm. And my ears detected no thunder yet. I had time. So, I headed toward the storm to get back over the summit earlier than planned and to descend to lower elevation by the time rain, thunder, and lightning hit.

It helped that I had just written an article (for the Telluride-based Ryder-Walker hiking tour company’s blog) on lightning safety, so I knew better what to do and what to avoid. I am reprinting a shorter version of that article here, to share advice on how to stay safe during thunderstorms. Here in southwest Colorado, we can expect strong electrical storms to return in mid-July during the traditional monsoon season.

5 Rules to Follow in a Lightning Storm

Mountain weather can change as quickly and dramatically as a moody teenager. One hour you’re hiking toward a summit in strong high-altitude sunshine, then the next, you’re zipping up a waterproof outer layer as ominous gray clouds converge and produce a clap or boom of thunder.

When you hear thunder, don’t wait for visual proof of forked lighting splitting the sky overhead to manage the risk of being struck. You can minimize the chance of a lightning injury by following these “rules” (explained below) during wilderness excursions:

Plan ahead to avoid or at least to mitigate the risk

Seek safer terrain in a thunderstorm (lower elevation, away from exposed summits or ridgetops, and away from tall solitary objects and standing water)

If you’re stuck on a high, exposed area, then crouch and minimize ground contact

Drop your trekking poles and avoid other metal objects

If you’re with a group, spread out about 20 feet from one another

You may see relatively clear sky or lighter-colored clouds in the direction you’re heading and conclude you don’t need to worry about lightning. But if thunder fills your ears, you’re hearing the sound that lightning makes—so lightning in fact is nearby and can travel to hit you.

How Lightning Works

What’s going on when a storm builds and produces lightning and thunder? Basically, warm air from the earth’s surface is rising and interacting with ice forming in the clouds above, creating static electricity, which the atmosphere discharges. A negative charge in the sky seeks to connect with a positive charge from the ground, and the connection point often is a tall solitary object, such as a big tree or a pointy peak.

The result is a spectacular flash of electricity. That, in turn, creates a shockwave of sound we hear as thunder.

Here's the good news: very few people are hit by direct lightning strikes—the kind of strike that zaps the top of a tree or touches a summit. And, few people are killed from lightning. In the United States, an average of 28 people died annually from lightning between 2006 and 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The bad news: Lightning injures are severe. You can be seriously injured or killed by ground current, which is voltage traveling through the ground from the strike point to where you’re standing or sitting. You also can be hurt or killed by “splash lighting” (a.k.a. a side flash), which is electricity jumping from one object (such as a tree or boulder) to you.

Plan Ahead to Avoid Thunderstorm Risks

Lightning hits people when they’re in the wrong place at the wrong time. So, learn about the region’s weather patterns, check the forecast, and then time your hikes to ascend peaks or traverse exposed ridges during good-weather windows, which usually occur early in the day. Also consider alternate routes to take at lower elevation if a storm develops.

If you’re stymied by a threatening storm, don’t let ego overrule good judgment—turn back and wait to tackle that stretch of trail.

Always pack warm, waterproof layers in case you must wait out a storm. If you must shelter in a grove of trees during a downpour and thunderstorm, for example, you could get soaked to the skin, and your body temperature would drop precipitously from lack of movement. Pack an emergency space blanket, an extra wool base layer, a lightweight poncho, and perhaps hand warmers to prevent hypothermia.

Also, plan your campsites in safer areas, especially if you’re using a tent with metal parts. Your tent could become more of a trap than protection. Metal, like water, does not attract lighting, but it conducts it—so if you’re lying in a tent with metal poles or stakes, perhaps next to a puddle, then ground current from a nearby lightning strike could be more likely to travel to and through your body.

Seek Safer Terrain

There’s a saying, “When thunder roars, go indoors,” because being outside is not safe in a thunderstorm. It’s best to seek shelter in an enclosed building or hard-topped vehicle with the windows up. (Open structures like porches don’t provide protection from lightning.)

If you’re hiking, you likely don’t have the option of closed shelters, so let’s review safer areas to go when thunder roars.

If you’re high on an exposed ridge or summit and see a storm building, alter your route, or turn back on the trail to get to lower, more protected elevation, such as in a grove of trees or in a low point between hills. A depression in the ground is a good spot, as is a dry ravine unless flash flooding is possible.

Avoid taking shelter near tall, solitary objects (such as under a single big tree). Also stay clear of standing water, such as ponds and puddles.

Minimize Ground Contact

If you’re stuck in an exposed, high area, and all your senses detect electricity in the air—your hair may even start rising from static electricity—then you’re in danger of being struck, and you must manage this worst-case scenario.

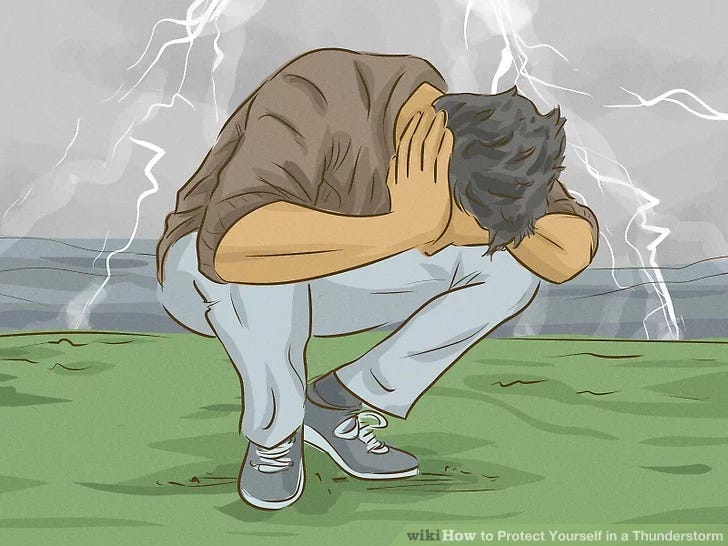

Don’t lie down! It’s a myth that lying down—getting as low to the ground as possible—will help. Rather, get in the lightning position (see illustration).

The most important aspects of the lightning position involve keeping your feet close together and keeping your hands from touching the ground. If you can balance on your forefeet with heels off the ground, that’s even better. Crouch down rather than stand (to reduce the chance that a direct strike or slide flash of current will hit you) and make your body into a small ball with head lowered. Clasp your hands over your ears to protect your hearing from thunder and to give you a place to put your hands.

If you become too fatigued to maintain the lightning position, then sit on your butt and hug your knees to your chest, with your feet and hands off the ground.

Staying in a crouched position with feet close together won’t protect you from a strike, but it will minimize the amount of ground current that flows through your body and can significantly reduce the severity of injury. By contrast, if you lie down and stretch out, with your limbs extending and touching different parts of the ground, then more electrical current will travel through your body, causing greater injury or even death.

Drop Trekking Poles and Other Metal Objects

When assuming the lightning position, you don’t need to chuck your metal trekking poles far away, but you should set them down a good distance from you in the worst-case scenario described above. The same goes with your backpack if it has a metal frame, and anything else metal, such as your smart watch, phone, crampons, or an ice axe. Metal from poles, tent stakes, personal accessories, and fence wiring all can conduct ground current, so don’t touch these objects when lightning threatens to strike.

As unpleasant as it is to visualize, metal jewelry or belt buckles can burn your skin if lightning travels through you, so remove these objects too if time allows.

Spread Out from Others

If you’re with others, you should spread out from each other out to improve the odds that one or more of you will remain unharmed and be able to help if lightning hits the ground and the ground current travels to strike individuals.

“Like the lightning position, spreading a group out is a last-ditch move in a dangerous situation,” says Liza Howard, a wilderness safety expert who teaches wilderness medicine for the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS). She says how far you spread out depends on the terrain and the group’s ability to manage themselves.

“If someone doesn’t have rain gear, and splitting up means that person is going to become hypothermic, it makes more sense to stay together and share an emergency blanket. You do want to keep within hearing distance of everyone. If you can get 20 feet from the next person, great. Spreading out doesn’t make you more safe, it just makes it more likely that someone will be able to take care of someone else if they get hurt.”

If one of your buddies gets hit by lightning, he or she may suffer burns, seizures, hearing loss, or sudden cardiac arrest. It’s a myth that this person is full of electrical current and therefore unsafe to touch. A person shocked by lightning will not retain the charge, so give that person aid as soon as possible, such as warmth, wound care, or CPR if necessary.

Meanwhile, monitor the storm. Ideally, you should wait 30 minutes after the last thunderclap to start moving again on the trail. To stay warm, try exercises such as marching in place. If you’re with someone who’s injured, however, you may need to get moving to lower ground sooner and to call for help.

A few final links and shout-outs for this week:

Cole of

wrote a useful guide to reservation systems for Colorado parks and peaks, detailing which ones need reservations and how to get them. If you’re thinking of traveling around the state to enjoy the great outdoors during the busy summer and fall seasons, read his post.I’ve restarted the Substack Chat thread with a query about summer reading. You, too, can post a question to start a thread and crowdsource advice there.

I recommend following iRunFar.com and their twitter feed for the best Western States 100 coverage. Let me know in the comments below if you’ll be around Olympic Valley and Auburn this weekend!

Thank you so much for subscribing. I hope you’ll share this newsletter and encourage others to subscribe.

So glad to finally read about Western States here in Substack. I ran WSER last year and have been writing about it a lot since then. Just left an incredibly deep mark on my life. /So excited to follow this years race this weekend!

So glad you got to help get Soon-Chul to the track in time! Bravo! Can’t wait to read this book!