The Story Behind the Hanging Flume 50K

A century-plus of wild history passed down from my grandfather

Welcome back! If you’re new here, I hope you’ll subscribe and check out last week’s anniversary post for an introduction to this newsletter’s purpose and content. If you upgrade to a paid subscription at $6/month, you’ll receive bonus content and an invitation to monthly virtual meetups.

Last Friday afternoon before I ran the Hanging Flume 50K, I sat in Telluride’s Sheridan Opera House watching a presentation by renowned environmental photographer James Balog, who documents receding glaciers. In stunning photos taken many years apart, massive swaths of ice morph into smaller shapes and leave behind the haunting beauty of an alpine lake or an open sea. His photos made the audience confront and contemplate human-caused destruction and adaptation, challenging me to fathom the world our grandchildren will inherit and to hold hope even as we feel helpless and grieve loss.

Serious stuff, yes. What does it have to do with an ultramarathon? It relates to the setting of the race I ran Saturday—a landscape that has been the scene of dramatic change and human-caused destruction but now, it seems to me, conveys cautious optimism—and to my role as a grandchild experiencing a landscape altered by earlier generations.

Sometimes I run ultras to race with a goal, and sometimes I simply show up for a supported long run in a place where I want to spend a day. This was the latter.

I traveled two hours westward to run around a high-desert plateau shaped with striated sandstone hills and bordered by steep canyon walls, carved by the San Miguel and Dolores rivers, where minerals color the layered earth in hues of red, yellow, and grayish-green. Roughly halfway between Telluride and Moab and sitting around 5000 feet elevation, the area is known as the West End because it’s at the west ends of Montrose and San Miguel counties, near the Utah border.

After white men bullied their way into this Ute territory in the mid- to late 19th century, the landscape and its small towns went through different eras that tell part of the story of the greater West: A gold rush that went bust. A ranch land where thousands of cattle roamed (and where at one point my great-grandfather and grandfather lived and managed the operations). A mill that extracted minerals and became the site of a company town, home to around 1100 people, named Uravan after uranium (used for atomic bombs) and vanadium (used to strengthen steel). A fervor to extract as much of those elements as possible during World War II and the Cold War. Then a realization that the town was so toxic and radioactive, it had to be razed and buried as a Superfund site, a drawn-out cleanup in the 1980s with a price tag of approximately $120 million. Then abandonment as uprooted, unemployed families moved away.

And now, slowly, signs of renewal. An uptick in students enrolled in the schools in the nearby towns of Naturita and Nucla. More startup business among the shuttered ones. More outdoor enthusiasts developing and playing on trails. More environmental cleanup and legislation poised to protect wildlife and public lands around the Dolores River.

And this event, covering 32 miles where all that history unfolded. It’s a race whose terrain reflects the varied uses of the place: rocky double-wide mining roads, smoothly graded county dirt roads, technical singletrack that horses and cattle used to traverse, and a bit of running on the paved shoulder of the highway.

Three guys who live near Telluride started the race last year to spotlight the West End’s trails, history, and communities, which chronically struggle economically. A nearby coal mine and coal-fired power plant shut down in 2018-19, eliminating some 130 good-paying jobs in an area where only about 1500 people live. Naturita and Nucla hope to boost economic development in part by recasting the mining and ranching region as an uncrowded alternative to Moab for mountain bikers, hunters, OHV drivers, and hikers and runners.

I applaud those guys—Sheamus Croke, Mason Osgood, and Dave Chew—for starting an ultra from the grassroots for the seemingly old-fashioned reason of growing and benefitting both the local community and the community of runners. They partner with nonprofits and try to generate donations for those groups that do good work in the region.

Side note: A week before the race, I read this article about Ironman joining UTMB to brand and monopolize marquee ultras globally, instituting a new system for entry that incentivizes running their UTMB World Series. The travel and entry fees associated with getting to the granddaddy event, UTMB, now looks a lot like the costly quest to enter and finish the Ironman championship in Kona.

The CEO of Ironman said, “Trail running looks identical to triathlons 30 years ago. Lots of races and events created by small groups of very passionate people, but most of these people don’t want the risk or work of scaling up. The natural step is being acquired by a company like ours. … Thousands of runners over multiple days is our sweet spot. We make sure all of our new races can scale to this.” [insert barf emoji]

Races I ran years ago that reflected the personalities of their founders—for example, Tarawera 100K in New Zealand by Paul Charteris and Speedgoat 50K by Karl Meltzer—sold out to UTMB/Ironman. The authentic emails that used to come from those race directors have been replaced with junky marketing e-blasts tied to merchandise and the area’s tourism. The events now number in the thousands and seem impersonal and entirely profit motivated. Hanging out with the race director—as I did when attending a barbecue with other runners at Paul’s house before Tarawera in 2015, or shooting the shit with Karl while picking up my bib in 2017—seems like a quaint thing of the past.

The point is, I love seeing local race directors develop and steward races for reasons that benefit the place and its community, not just to scale up and make money. Now, let’s get back to this race report and history lesson.

The young race with mostly young runners drew only 41 of us to the start line, located at the historic Uravan ballpark that’s now a campground. The event’s small size, with everyone seeming to know almost everyone, generated the feeling of a party or picnic at daybreak.

I chatted with several friends also running it, and then we took off down the highway for a nice, easy mile warmup. Then we turned onto a mining road that rose about 1400 feet, transporting us to the sprawling, sandy plateau whose cliffs drop off to the Paradox Valley on one side, and the Dolores and San Miguel rivers on other sides. Far in the distance, we could see fresh snow on the La Sals to the west and on the San Juan Mountains to the east.

I wanted to revel in the high-desert beauty and let my mind reconnect with the spirits, including those of my grandparents, who once lived and worked in this place, but for about nine miles, I literally and mentally felt bogged down by treacherous mud.

Thick, heavy, clay-like mud stuck to the shoes’ tread and added several pounds of weight to each foot. The extra weight and unstable footing strained my knees and hamstrings. Frustration mounted. I resorted to trudging more than running, taking solace in the fact that runners around me shared the struggle. “Embrace the suck,” as the saying goes. I reminded myself that a desert race like this on the first day of October could be punishingly hot, and the sky could be brown from wildfire smoke. Isn’t cool dampness and a sky filled with dramatic thunderclouds better?

We felt some sprinkles but thankfully dodged a morning downpour that looked like a steel-gray curtain hanging from the sky. I made it to the Mile 10 aid station and gratefully accepted the encouragement of a trio of volunteers from Telluride. The next stretch of the route took us along a well-graded dirt county road, which in the opposite direction leads to an expanse of rock covering an area many football fields in size, fenced off with warning signs, where Uravan’s toxic town and tailings are buried in perpetuity. But we didn’t go that way; we ran toward the beautiful river vistas instead.

With no more mud slowing me down, I endeavored to run as best I could. Gradually I caught, passed, and gapped four runners ahead. A short out-and-back section took us to an overlook to see the vast, sparsely populated river basin known as the Paradox Valley, so named because the Dolores River intersects it perpendicularly and flows through its middle, instead of running through the valley lengthwise as rivers in valleys normally flow.

On this isolated plateau dotted with scruffy, gnarled piñon, my stride opened up, and so did my mind. I thought less about running in the present and let myself time-travel, imagining the past. It’s not too hard to imagine, because my grandpa David S. Lavender vividly described this exact place, and his life as a rancher on it, toward the end of his memoir One Man’s West.

Let me detour to that time and share a glimpse of it.

My grandparents lived at and briefly owned the Club Ranch, whose headquarters sat right next to the Joe Jr. Mill and Camp where the town of Uravan developed in 1936 and blossomed through the 1950s. In this 50K race, we run next to the river right where the Club Ranch and Uravan used to be, though only some rotting wood corrals and a historic marker are left as reminders of that era.

Established in the late 19th century and named for the ranch’s brand—the shape of a club from a playing card—the Club Ranch became one of the most successful and best-known cattle operations in Colorado a century ago. A December 14, 1913, issue of the Montrose Enterprise newspaper described the ranch and its setting as: “The Club Ranch is the wayside inn, as it were, of a vast territory where the wonders of nature are abundant and supremely magnificent, but where the abodes of man are exceedingly few and far between. The Club Ranch is a landmark of Western Colorado.”

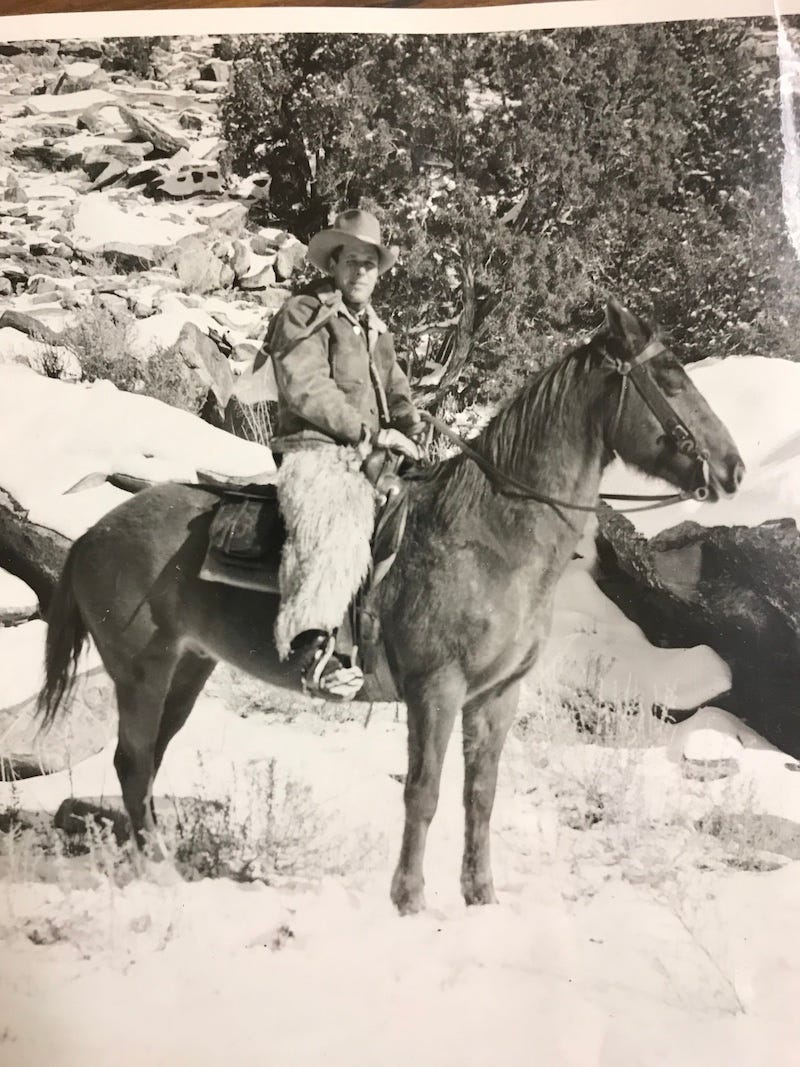

My grandfather’s stepfather, Ed Lavender, bought the ranch sometime in the early 1920s. He’d buy cattle from a ranch in Utah, next to what’s now the Needles District of Canyonlands National Park, and a dozen or more cowboys would spend days herding the cattle to the Paradox Valley and then to the Club Ranch, where they’d spend winter and spring at lower elevation. Come summertime, they’d move all those cows by horseback to Beaver Park at the base of the Lone Cone, near Norwood, for grazing. Theirs was the last generation to move herds and conduct roundups that way, before automobiles, stock trailers, grazing laws, and fencing changed ranching.

“In the course of our wanderings,” Grandpa wrote, “we covered a territory perhaps a thousand square miles in size, and since most of our supplies were carried in small cotton bags—dried fruit in one, coffee in another, beans, sugar, sowbelly, dishes, and canned goods—the trips were known as ‘greasy-sack rides.’”

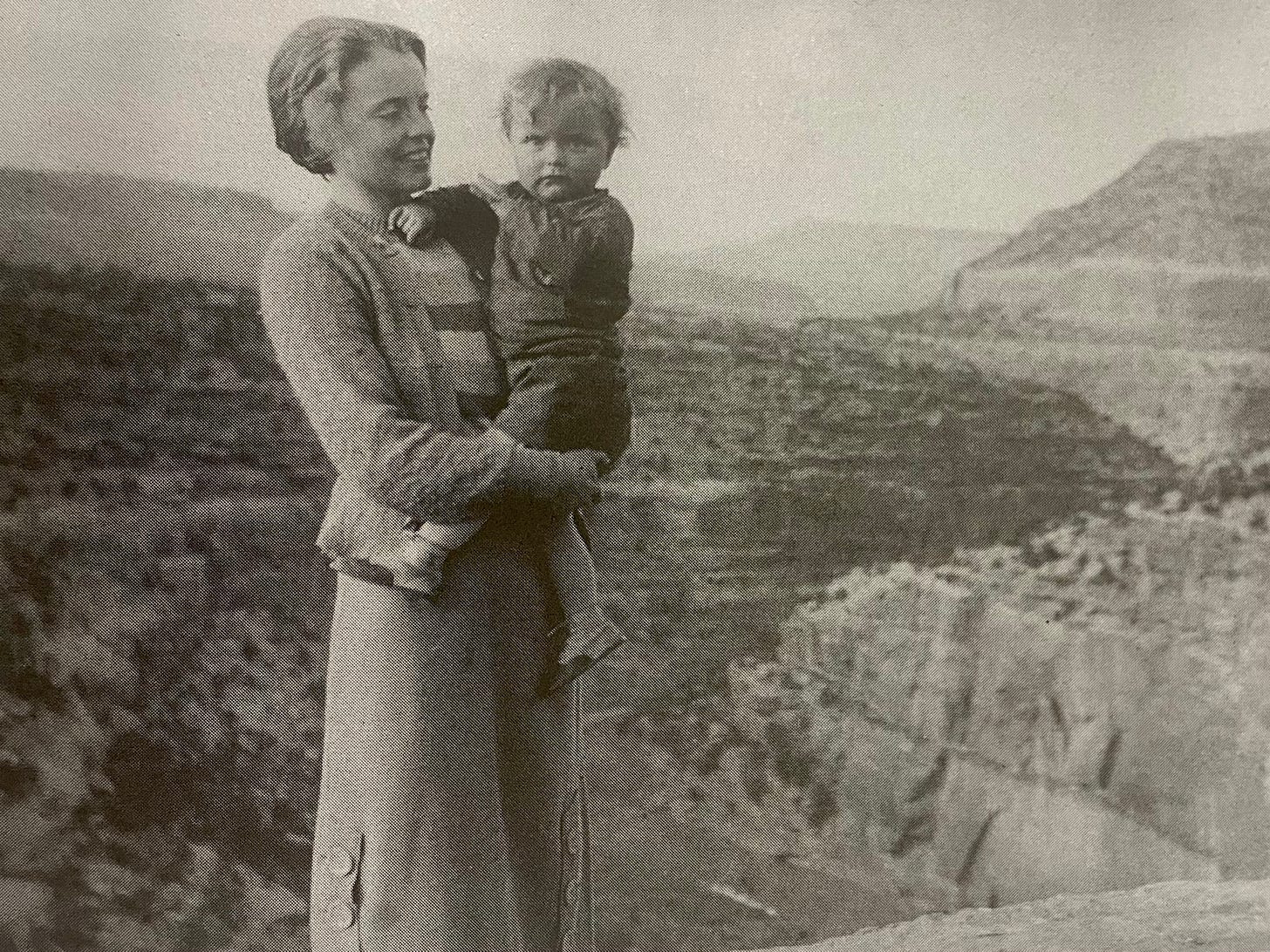

Grandpa, who graduated from Princeton and then spent one year at Stanford Law School, learned from his stepfather how to ranch during summer breaks from school. He left higher education during the Depression in need of work for money. For a while he worked as a miner at Camp Bird in Ouray, then became a full-time ranch hand. When his stepfather died of cancer in 1934, Grandpa—in his mid-20s, married only a year, with a newborn baby (my dad)—had to shoulder the massive responsibility of the Club Ranch operations. His younger brother Dwight, a founding member of the San Juan Mountaineers and a famous climber, had also just died from polio.

Grandpa did the best he could. So did my grandmother Martha (who went by the nickname Brookie), being isolated with only a few other women to help her cook for all the ranch hands. When they lived at the Club Ranch, Grandpa writes, “It was 10 miles to the nearest neighbor’s, 22 from an electric light, more than a hundred from a competent doctor. Consoled by the purchase of a battery-powered radio, Martha loaded the car with a first-aid kit and several books on ‘what to do until the doctor comes.’ Away we went.”

In the race, around Mile 25 as we ran down the twisting, technical Shamrock Trail that drops about 1000 feet in elevation, I recalled Grandpa’s story of riding this trail—what he described as “a mustache of a path that clung to the lip of the slope”—when it was icy, and the horse’s footing unstable, at dusk in a hurry to get back to the Club Ranch on Christmas Eve, 1934. “Down Shamrock we went with just the tips of our boots in the stirrups, ready to leap clear if the horses fell.”

I too risked tripping and falling, so I had to stop to look up and take in the view—one of the best views along the race course, overlooking the San Miguel River’s sheer walls rising several hundred feet above the water.

As improbable as it seems, metal brackets hang in a line along the middle of this canyon wall. The metal supported the base of the hanging flume, the ultra’s namesake. Twelve miles of a wooden water chute, suspended by those brackets, was built in the late 1880s by workers hanging from ropes. They intended to use the water flow for hydraulic mining. But it shut down after only a couple of years because the gold mine wasn’t viable.

Grandpa described the history of the hanging flume this way: “Engineers swore that hydraulic mining would uncover a fortune, but the giant nozzle of a hydraulic hose requires tremendous water pressure, and the only source of water—the river—was four or five hundred feet below. ‘Never mind,’ said the engineers, ‘We’ll hang a wooden flume along the cliff face!’ It was a staggering piece of hopefulness.”

He goes on to describe all the work that went into creating that long wooden box on the side of a cliff—all the lumber that had to be shipped in by wagon, all the scaffolding and roping that had to be fixed in place—and in the end, he writes: “It was a total failure. Why, I do not know. The two or three local residents remaining who saw the conduit built are vague in their accounts. They claim the job cost more than a million dollars [in 1880s prices]. Water was run through it just once. The thing worked, but some miscalculation occurred at the receiving end, and the entire project went glimmering. It is said that the head engineer promptly blew his brains out.”

On the plus side, he added, they were able to salvage much of the flume’s wood to build some of the Club Ranch’s barns and furniture, including the desk that my grandfather used to write on and that my brother still uses today.

By 1936, my grandparents couldn’t hang onto the ranch’s operation; deep in debt, they sold it and moved to Southern California, where Grandpa started a new life as a writer and teacher. Also in 1936, the town of Uravan took shape. When Grandpa wrote his first edition of One Man’s West in 1943, he described Uravan as home to hundreds living on tree-lined neighborhood streets, in a town with stores, a gas station, and community pool. “Overnight almost it sprouted, and the incomprehensibility of it will not leave me, for Martha and I learned to live there in the dead period between two eras. Then no spot could have seemed farther removed from the turmoil of industry or the hot fingers of war.”

In 1955, the summer after my dad graduated from college, he and my grandfather road-tripped back to Uravan to see how the old ranch had been replaced by the uranium mining boom, the ranchers “elbowed aside and left bewildered by the abrupt shifts in values, the hurry, the speculative frenzy.”

My dad recalled that Grandpa was dumbfounded by the new, smooth roads and the population influx at the ranch’s old site. “The country was teeming with prospectors,” my dad wrote. “We watched small planes scooting around the edge of the rimrock as passengers held Geiger counters out of the windows, awaiting indication of radioactive material.” Grandpa then updated One Man’s West with a 1956 edition that added a chapter about how the uranium mining boom transformed the West End.

Sixty-six years later, I run here viewing the aftermath of that boom’s decline—the quiet, relatively isolated and uncrowded landscape. I ache for my dad and grandpa, neither living anymore, wishing they could be with me as I run the final flat miles of this race past the old ranch headquarters and the Uravan townsite, now just an empty, grassy fenced-off meadow with no-trespassing signs. I would like them to experience the beauty and peacefulness of this place now, and I’d like to pepper them with questions about their time here.

After I finished the race in 6 hours, 49 minutes (results), I socialized with all the runners and volunteers, all of them younger than I. I wondered how many knew about the convoluted history of this race route, and how the creation of an ultramarathon here marks the latest twist in the crazy story of what has taken place, ever since that folly of a flume was built, where the San Miguel and Dolores meet.

I wanted to share the old timers’ stories more than mine, so now you know.

For more info on the West End and its history:

Visit the Rimrocker Historical Society website and museum in Naturita

Read One Man’s West

And perhaps also this report on my old blog, describing my 54-mile solo run on the Rimrocker Trail from Nucla, through the hanging flume area, to the Buckeye Reservoir on the border of Utah

If you go:

Check out the West End Trails Alliance site for loads of info on the region’s trails

Visit Wild Gals Market in Nucla

Stay at Camp V in Naturita or the Vestal House B&B in Nucla

And run the 2023 edition of the Hanging Flume 50K

Thanks also to historian Ike Rakiecki for his research on the Club Ranch, presented in this video.

Oh wow! What a beautiful essay and entry into this remarkable place. I feel like you have managed to weave all of us into this history. Thank you for sharing!

Such a thoughtful read, Sarah. You take us on a real journey here; thanks for being the first thing thats made me stop and slow down and just rest, at all today. Bless you x