The Stage Race Cure for Stage Fright

How an extra-long, extra-tough ultra changed and emboldened me

Today I’m sharing why a certain event—a weeklong race—means so much and how it has affected me. Do you have any athletic event or social/cultural gathering that has affected you deeply and to which you feel drawn to return? (For example, I’ve heard people talk about the Hardrock Hundred or Burning Man this way, as being deeply meaningful and becoming a pilgrimage.) I’d love to generate a comment thread that shares these experiences, so please consider describing your life-altering event/gathering in the comments below.

First, some facts

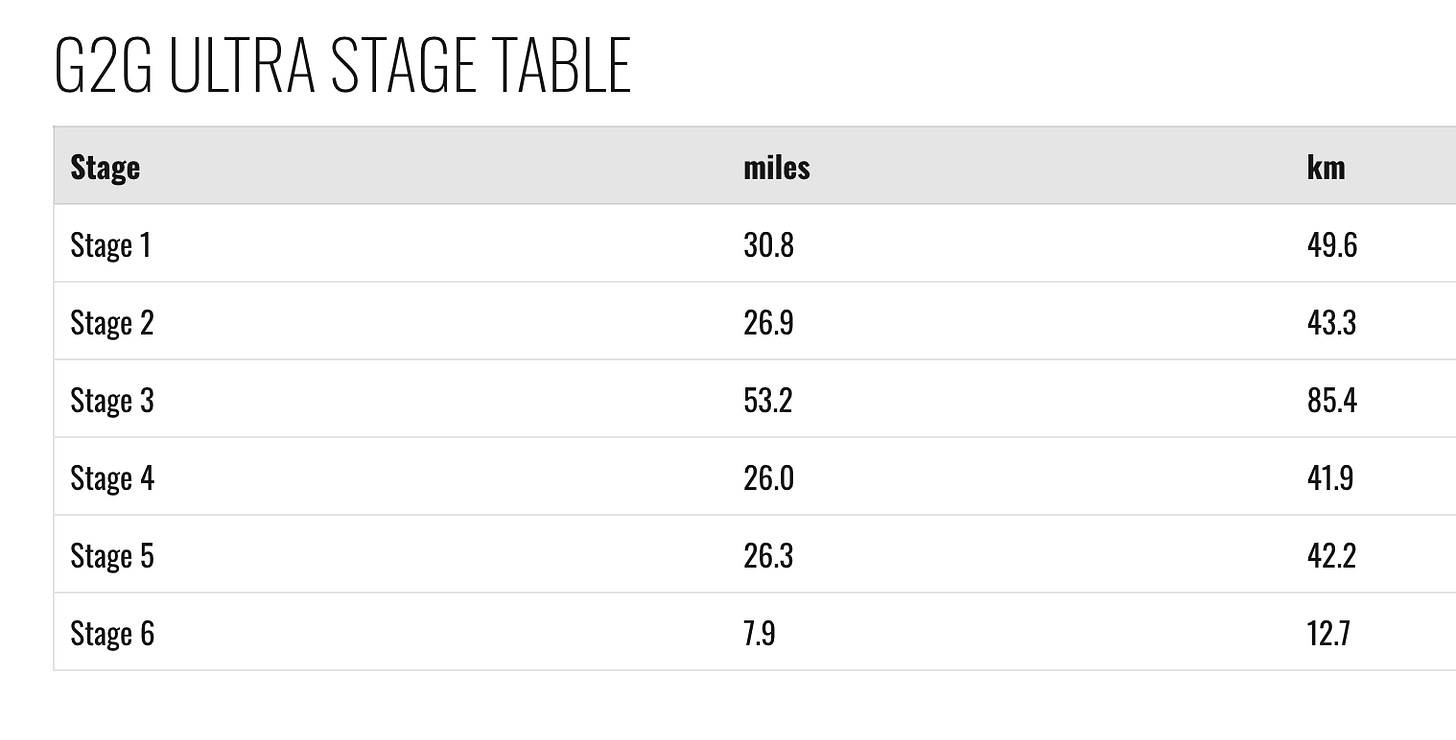

The Grand to Grand Ultra, which runs September 22 - 28, is a 170-ish-mile race broken into six stages. Each day, competitors race a segment and then stop at a camp where volunteers have set up communal tents. We recover at camp and spend the night, then race again the next day. In this way, each day is a fresh-start race, which appeals to me more than continuous extra-long ultras (such as the new crop of 200+-milers) in which competitors battle sleep deprivation midway and devolve into sleepy slogging. Winners in the stage race are based on their cumulative time.

The Grand to Grand is self-supported,1 which means we carry everything for the week—food, clothing, sleeping gear, required safety items—on our backs. The organizers provide communal tents and hot water at camp (so we don’t need to carry a stove or tent), and provide water at checkpoints, but otherwise if we need something, it’s on us. The event therefore demands self-sufficiency and lightweight, minimalist choices. (I’ll share the details of what I’m carrying in a later post.)

The organizers, Tess and Colin Geddes, started the Grand to Grand (G2G) in 2012 as a North American version of the notoriously difficult Marathon des Sables (MdS) desert stage race in Morocco. They created an arguably more difficult race. The G2G is longer, with each stage having a bit more mileage, and at altitude with greater temperature variation, from very hot desert plateaus to freezing-cold nighttimes in higher-elevation forests. As with the MdS, the G2G attracts an international field of competitors with many from Europe, Asia, Canada, and Latin America as well as the United States.

But the Grand to Grand Ultra is much smaller than the better-known and longer-established Marathon des Sables. I’m one of only 58 participants this year. When I ran it a decade ago, it had about 110 participants. I’m truly surprised the Grand to Grand hasn’t caught on more in popularity, even though it attracts some top international competitors. It’s relatively low profile in terms of media coverage, especially in this era of livestreaming and hyping ultras such as Cocodona or Western States. But that appeals to me.

It’s off the grid and gritty—no crew, no spectators, no commentators, no mid-race posting to Instagram or any other GPS or cell connectivity allowed. The event only posts a daily results update to the event’s Facebook page.

It’s called “Grand to Grand” because it starts at the north rim of the Grand Canyon in northern Arizona and ends at the top of the Grand Staircase formation, on the Pink Cliffs near the edge of Bryce National Park in southern Utah. Along the way, we run through the Kaibab National Forest, scramble up red-rock buttes, crawl up and slide down dozens of dunes in the Coral Pink Sand Dunes State Park near Kanab, weave through a narrow slot canyon, and end with an ascent through aspens turning golden. Much of the terrain features deep sand.

Deep sand + 20-pound pack + desert heat + limited calories = slow endurance pace with a lot of hiking mixed into the slow running. The tortoises tend to beat the hares who blow up and drop out.

This will be my fourth time participating in it (I did it in 2012, ‘14, and ‘19), and fifth time doing this format of a self-supported stage race. (I did the organizers’ one-time spinoff event called the Mauna to Mauna on the Big Island of Hawaii in 2017.)

How I got there—and why I keep returning

I was in our remodeled kitchen, approaching my 43rd birthday in 2012, when the email arrived from an editor at Trail Runner magazine about this new race and an opportunity to cover it as a competitor.

A week in the desert, self-supported, running farther than I ever had. What could possibly go wrong?

My laptop sat on the marble-topped island. My husband Morgan was working at his startup legal-services firm, and our son and daughter, then 11 and 14, were in fifth and eighth grades at our local school. The editor emailed me about the potential assignment because I occasionally wrote features for running and lifestyle magazines after my daily journalism career fizzled when I quit a newspaper job to raise our kids.

At that point, I was still relatively new to ultramarathons. I hadn’t yet done a 100-miler and certainly never did anything like this Grand to Grand Ultra.

I wondered, did the editor think of me for this assignment because everyone likes a fish-out-of-water story? Since I was an urban, privileged stay-at-home mom, he might have assumed I’d struggle in the middle of a desert with sand, heat, hunger, and even snakes. (Yes, there would be a snake encounter.) Maybe I’d show him—and myself—that I could rise to the challenge.

When our kids were babies and toddlers, we watched Survivor on TV, and I nurtured a secret desire to be on the show—to test myself against the elements. This email in spring of 2012, inviting me to participate in the Grand to Grand and then write about it, made me think of Survivor and feel a desire for adventure, escape, and independence.

In my early 40s, I needed something of my own that would fortify my sense of self-worth and identity. My most recent job outside the home had been supporting my husband in starting his new business by doing admin and PR tasks. I volunteered at my kids’ schools and served on a nonprofit board. While my devotion to parenting filled my heart and took most of my time, it didn’t satisfy my ego. I didn’t have or do anything that created an identity and source of pride outside of my family, other than running and competing in races.

In couple’s therapy, which we sat through for two tough and trying years in the mid-2000s, our therapist held her two index fingers together touching, as if her fingers were leaning into each other, and she explained metaphorically that this kind of lean makes a weaker structure.

“Since high school,” she pointed out, “you and Morgan have been leaning on and depending on each other.” Then she held her two fingers close together but separate and parallel. “Strong structures are built like this,” she said, “on a solid foundation, with the beams running together but independent.”

Could the Grand to Grand help me stand stronger and be more independent and confident? Could I take care of myself out there on my own, and leave my husband and kids for the week to take care of themselves, too?

Could I survive?

At the inaugural 2012 event, I showed myself and others that I had what it takes to traverse the landscape in harsh conditions and take care of myself along the way.

When unexpected problems arose, I met the challenge, such as when I tripped and fell into a spiky plant (everything in the desert is spiky, it seems) and a thorn punctured my plastic water bottle. Without the capacity to carry enough water, I would dehydrate and drop out of the race, so I used the bit of duct tape I had the foresight to pack and patched it, then spent the rest of the week carrying the bottle upside down, with the patched hole on top, so it was less likely to leak. When a blister on my toe became so dirty and painful that hot red streaks from infection traveled up my foot, I started antibiotics that I also had the foresight to bring and bandaged my toes to keep the infection under control.

I thought I would be in the mid- to back of the pack. Instead, I kept chasing and leapfrogging the two women at the front. Ultimately, a British woman who held a world record for a week of treadmill running—517 miles—won. This event attracted endurance freaks like her. And I was following in her footsteps.

I finished third female and seventh overall in the 2012 edition, out of a field of about 60. Two years later, in 2014, I ran the Grand to Grand again and finished second female, and then I ran its spinoff event in 2017, called the Mauna to Mauna Ultra, on Hawaii and finished third female there.

Something happened to me during those five years, from 2012 to 2017, because of those solo weeks away to race. When I returned home from finishing one of those events, I felt emboldened and intrepid in ways I hadn’t been before.

Public speaking? Not such a big deal now—I can find my voice in front of a crowd. Earthquakes and fires? I’ve got this, I’m prepared to save myself and my family. Creeper knocking on my front door? Better not fuck with me.

After the Grand to Grand, I discovered my spine for a leadership position on a board of trustees. (I even stepped up to co-chair a multimillion-dollar fundraising campaign with a man well known as a business titan, who had made Forbes’ billionaire list and who previously intimidated me. After the Grand to Grand, I could answer his emails with my straight opinions, less worried about how he’d react or what he thought of me.) I also figured out that I wanted to start my own coaching business, which I did and developed successfully for nine years. And I took the leap with my husband to move to Colorado and build a home from scratch.

I wasn’t as scared to try new things or go head to head with other people. It’s like the experience of excelling at the Grand to Grand Ultra gave me superpowers.

In 2019, as a 50th birthday present to myself, I returned to the Grand to Grand Ultra. I wanted to figure out what to do with my fifties and beyond. Really, what’s my calling? I channeled all my experience and endurance into a peak performance and finally won it—first female, and the only woman in the top 10 overall, in spite of getting an hour penalty after Stage 5 for running too low on food.

As I ran the final stage in 2019 through an aspen forest where the leaves were turning yellow-orange, alongside the tall, lumpy vertical red rock formations called hoodoos that cluster around the rim of Bryce National Park, an answer came to me: This, this is what I am meant to do; this is where I find meaning and friends. Long-distance running is my calling and improves every facet of life.

I figured I finally won the race because if you do something long enough, you eventually get good at it. Simple as that.

But it’s actually not that simple, because five years later in 2024, I’m declining physically from that peak and trying to make peace with this midlife body’s slowdown. I’m learning that we can’t always keep improving, but we can change our definition of “success.” Now, being successful as a runner feels less competitive for me. It means showing up and running however feels right, doing the best I can with this over-the-hill body.

Winning the Grand to Grand at 50 felt like a lifetime achievement award. I thought I’d say “enough.” I thought I’d had my fill. The single-day ultramarathons that I still run—in spite of a body that needs to downshift to hiking more frequently to catch my breath, and in spite of a knee with worn-out cartilage that protests when I bend to squat—provide enough purpose, adventure, and camaraderie to keep me satisfied as an ultrarunner.

And yet, everything about the Grand to Grand—its white canvas tents, sandy tracks, vermillion cliffs, piñon forests, international competitors, even the over-salted dehydrated meals-in-a-bag—exerts a pull and calls me back. That’s why I’ve decided to return to the Grand to Grand Ultra one more time.

At 55, I feel I have unresolved issues to probe out there in the desert. In journalism, for any story, we learned to get the five Ws and the H—the who, where, when, what, why, and how. I’m still missing a W, the “why,” plus some of the “what.” Why have I been running for more than half my life, and why do I want to keep at it? What shaped and compelled me to do this?

I want to retrace my past as I retrace my steps in the desert on that 170-mile route from northern Arizona to southern Utah.

To be continued.

The Public Lands Rule and my fundraiser

As mentioned in past posts, I’m raising money and awareness for Conservation Lands Foundation, which enhances and expands protections for sensitive public land managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The Grand to Grand Ultra’s route runs through or near many portions of public lands that Conservation Lands Foundation (CLF) has advocated to protect, and others that are threatened.

With each newsletter, I try to spotlight an aspect of Conservation Lands Foundation’s work. Let me tell you about the new Public Lands Rule, for which CLF advocated and now is helping to defend after the states of Utah and Wyoming filed lawsuits to prevent the BLM from implementing it.

To quote from CLF’s news release: “The Public Lands Rule, which went into effect in June, clarifies that managing BLM land for conservation fits squarely within its multiple-use mandate, and that conservation sits on equal footing with other uses. Specifically, the Rule provides BLM guidance for putting conservation, cultural values, access to nature, wildlife, renewable energy, and climate change mitigation on equal footing with mineral extraction and oil and gas development across the West and Alaska. This clarification is necessary, because the vast majority of BLM lands are currently open to extraction and other commodity-driven development.”

This is just one reason I support the work of Conservation Lands Foundation. I hope you’ll visit their website to learn more.

I’ve raised $3300 from 33 donors so far—easy math, $100 average donation. But donations of any size are appreciated; if you’re willing to chip in $10, I’d sincerely appreciate it! I’m trying to get to $5000 by the time the Grand to Grand Ultra ends.

Please use this button to visit my GoFundMe page; every dollar raised goes to the Conservation Lands Foundation, and gifts are tax deductible. If you prefer to give another way (such as by check or Donor Advised Fund), that’s fine; you can get info on how to donate to CLF through their website, then tell me about your gift, and I can add it to the fundraising total.

I encourage you to comment on the prompt at the start—do you have any athletic event or social/cultural gathering that has affected you deeply and to which you feel drawn to return?

However, last year the organizers introduced the Supported category. Supported runners must still carry a minimum of gear and hydration while covering the route, but they get their food and sleeping gear transported from camp to camp. Most competitors still register in the Self-Supported category. The Supported category is viewed as a way to encourage newcomers to try stage racing and to help those who may be at risk for missing cutoff times.

You're bringing back memories of a bike trip I did way back. Bryce, Zion and the northern rim of the Grand Canyon. We camped one night at coral pink sand dunes. That was an incredible place. All of them were.

Not so much life altering, but I keep thinking about a moment on an ordinary after work run in the winter a few years back. There's this podcast called Wild Card and the "prize" is to go back and relive any moment in your life and not change a thing about it. So, I keep thinking mine would be this thing that happened on that run. I was coming through the Nature Preserve on the campus where I worked and it started snowing. Hard. I couldn't see ahead or behind. I stopped and just put my face to the sky with the snow swirling all around. And I felt like I was a part of everything. This was the world embracing me. And me embracing it. I ended up writing a poem about it.

Can't wait to hear about your adventure!

I've written about the San Diego 100 a lot, both running it and volunteering for the race. My family and I have spent years helping out at the race, and we've all had some amazing bonding/growth experiences. More recently though, our Mountain Rescue team does a weekend training every month, and there's a special one every October. We take the new recruits up to the mountains and run scenarios to see if they are a good fit for us, and/or we are a good fit for them. It's a struggle mentally and physically usually under pretty harsh conditions, but it always amazes me how close we get to each other in a short amount of time. Similar to ultra running, but I think the camping and survival aspects of the weekend add to the experience, making it closer to the stage race atmosphere you described.