This week’s installment features a followup to an earlier post about training (and playing catchup) for a big goal, and a segment on trail crowding and stewardship. If you haven’t subscribed, I hope you will. Those who subscribe at the supporter level receive occasional bonus posts and are invited to a monthly online chat. The next one happens Wednesday, August 28, 5pm Mountain.

One month from now, I’ll travel to Kanab, Utah, and get on a shuttle to the north rim of the Grand Canyon. Then I’ll camp overnight and start the weeklong 170-mile Grand to Grand Ultra self-supported stage race on September 22. This is a story of one of my last long training runs in preparation for it—a story I hope will help any runner gut out a long training run.

Preparing for extra long, extra tough ultras is a lonely grind. You have to put in the time on feet and, for a self-supported race like this, practice with the necessary gear.

This story starts last Friday in the parking lot of the Walgreen’s in Montrose. No, scratch that, it starts in the Montrose regional hospital an hour prior.

I went to the hospital in the morning for an MRI. Who gets an MRI for knee pain and then runs a marathon, and what would my insurance company say about that? I do, and I don’t want to know.

My orthopedist at the Steadman Clinic in Vail ordered the MRI to assess the level of damage to the cartilage under my patella and to confirm that the pain on the lower lateral side of the knee, at the tibia head, is simply inflammation from a stressed iliotibial band, where it attaches to the bone, and not the start of a stress fracture.

Recently and thankfully, my knee has been feeling blissfully normal, thanks to the ortho’s injections. I got a shot for hyaluronic acid in my knee at the start of summer, which cushions and lubes the area around the degenerating cartilage, and then I got a cortisone shot in the painful spot where the IT band attaches to the tibia. Now my knee is functioning and feeling pretty darn good. But will it last?

The younger me thought that masking pain was bad and does more harm than good. The older me is more compromising, willing to carefully use some limited medical intervention to put more miles on my inner odometer while I focus on a goal on the horizon. I know I’ll work on addressing the root of the problem—overuse and flawed biomechanics—with more physical therapy when I take a break from higher-volume training later in the year. For now, I have a mere three weeks left to train, followed by two weeks of tapering. I needed this successful training run on this day.

I went to Montrose, 90 minutes from my house, not only for the MRI appointment but also for the heat. I should be adapting to a warmer climate, training my body to sweat earlier and more while I tolerate the discomfort. But it’s been cool at my house, with afternoon rainstorms in August. Montrose would at least reach 90 degrees by midday.

What will the weather on the route through northern Arizona and southern Utah deliver one month from now? Who knows, it could be triple-digit temps on the wide-open desert plateaus, but it also could rain enough for flash flooding.

I had stuffed my new Raidlight pack with extra reservoirs full of water, miscellaneous pantry items like bags of rice and nuts, two ankle weights that weigh three pounds each, and a bulky jacket to fill all the spaces and prevent stuff from bouncing around. I filled the front pockets with sweet and salty snacks, comfort items like sunscreen, and more water bottles. The luggage scale put it at 19.2 pounds.

This new pack is not quite as ultralight as the one I initially intended to use, but two weeks ago, I gave up on the first pack. It cut into my collarbone so much that it felt bruising. This new pack has better padded shoulder straps, a sturdier construction, and fits more comfortably all over. It weighs a bit more—20 ounces, or 1.2 pounds, compared to the ultralight pack’s 11.5 ounces or .7 pounds. The tradeoff is worth it for comfort, but I’m being careful with every ounce.

For a self-supported stage race, every ounce and every item that takes up space matters. I’ll carry my meals and snacks for the week, plus a lightweight sleeping bag, sleeping pad, a few extra pieces of clothing, and required safety gear. It’s nearly impossible to make it all fit. When it’s all on my back and the water bottles are full, it’ll weigh around 20 pounds. That sounds light by backpacking standards, but try running instead of hiking with 20 extra pounds concentrated on your upper body. It feels like an unnatural heavy gravity force pulling downward, making every footstep off the ground for a running stride an extra effort.

I left my car and set out on the sidewalk, wearing my river hat instead of a running hat for full-brim protection, and settled into a shuffle-jog that counts as running with a pack. My pace on this flat, smooth surface was around 11 to 11:30 per mile mile, which is around the best I can do when weighed down. When I’m slogging through desert sand and hiking up steep buttes in the Grand to Grand Ultra, a 15-minute average pace will be relatively speedy.

Pack training runs therefore are an exercise in cultivating patience—in making peace with being so slow. My mind wants to cover six miles or more in an hour. But with the pack, heat, and sand, I have to get used to only four or at best five miles an hour.

In the first mile, I ran past my mom’s old assisted living home and silently said hello and imagined waiving to her. I stared at the patio furniture in the distance where we used to sit and admire the horses in the open pasture next door. Pangs of nostalgia and a desire to visit her and her caregivers hit me now, even though those visits often were difficult due to her dementia. She’s been gone for over two years now. Memories of her remind me that I have a decline and end time in my future, so I better reap the benefits of my body and its abilities now.

Montrose neighborhoods feature relatively modest newer tract homes, but a few older ranch houses still have expansive yards with horses in them, and when I ran by one, I spotted a small young one who trotted toward me to say hello. Her ears were so big, I realized she’s a mule. She clearly wanted my attention. I paused my watch to pet her and admire her friendliness, and I decided this young mule would be my spirit animal for this training run. I’d be stubborn like a mule and frisky like a filly.

Early on, I put in my AirPods and started a podcast. I’m enjoying—make that, relying on—audio entertainment to get me through long runs so much now that I’m considering taking the AirPods and a portable charger on the Grand to Grand, something I didn’t do for the prior weeklong races. When I did this event in 2012, ’14, and ’19 (plus its spinoff stage race on Hawaii, the Mauna to Mauna, in 2017) I went completely unplugged. I never listened to music, just sang songs in my head. I never used my phone (which we’re not allowed to use during the event for calls, texts, or getting online, and connectivity is nearly nonexistent anyway). I had a Timex Ironman watch that only functioned as a stopwatch, unlike my Garmin Fenix 7 that measures pace, distance, elevation, heart rate, and numerous other metrics. Now, I feel hooked on my Garmin and on my phone’s music. I’m leaning toward taking these devices and an ultralight portable charger, but that adds up to another 8 ounces at least. I haven’t made up my mind yet.

On this training run, I settled into a mulish tortoise pace and tried to relax as much as possible. The challenge became running what I could reasonably sustain rather than succumbing to walking most of the time.

The white noise from the swish-swish of the pack on my back filled my ears, even with headphones playing a vintage Bon Jovi album. Sweat seeped through my shirt and ran down my cheeks. I kept pausing to refill my bottles and mix in electrolytes with the water. Then I paused to cool off in the shade. I told myself to get going, to “make hay while the sun shines,” a saying that came to mind as I watched a farmer methodically cut tall grass in a field.

After a 12-mile loop, I hit the overly familiar and monotonous Montrose bike path. I ran the uneven dirt shoulder to better mimic a trail. Only one significant hill interrupts the long path, and I went up and down it twice.

I kept wanting and needing walking breaks due to the fatigue of my shoulders and legs from the pack, and my heart rate was higher than usual in the heat. I kept picking a spot in the distance to run to and then rewarded myself with a walk break, but then I realized I was wasting mental energy on constant bargaining with whether and when to walk. “Shut up and run” became my mantra, and I ran a little bit more, walked a little bit less.

Five hours into this outing, with the temperature at 90 and heat radiating off the light-colored ground, I contemplated ending around mile 22 instead of doing another four-mile out-and-back on the northern spur. But I had set out to do a full marathon, because five of the six stages in the Grand to Grand Ultra range from 26 to 53 miles, so a single-day marathon should damn well feel manageable if I’m going to meet the challenge of marathon-plus back-to-back runs during that week in the desert.

So I shuffle-jogged, tried to practice acceptance, and focused on the details around me such as wilting sunflowers that symbolized my fading optimism.

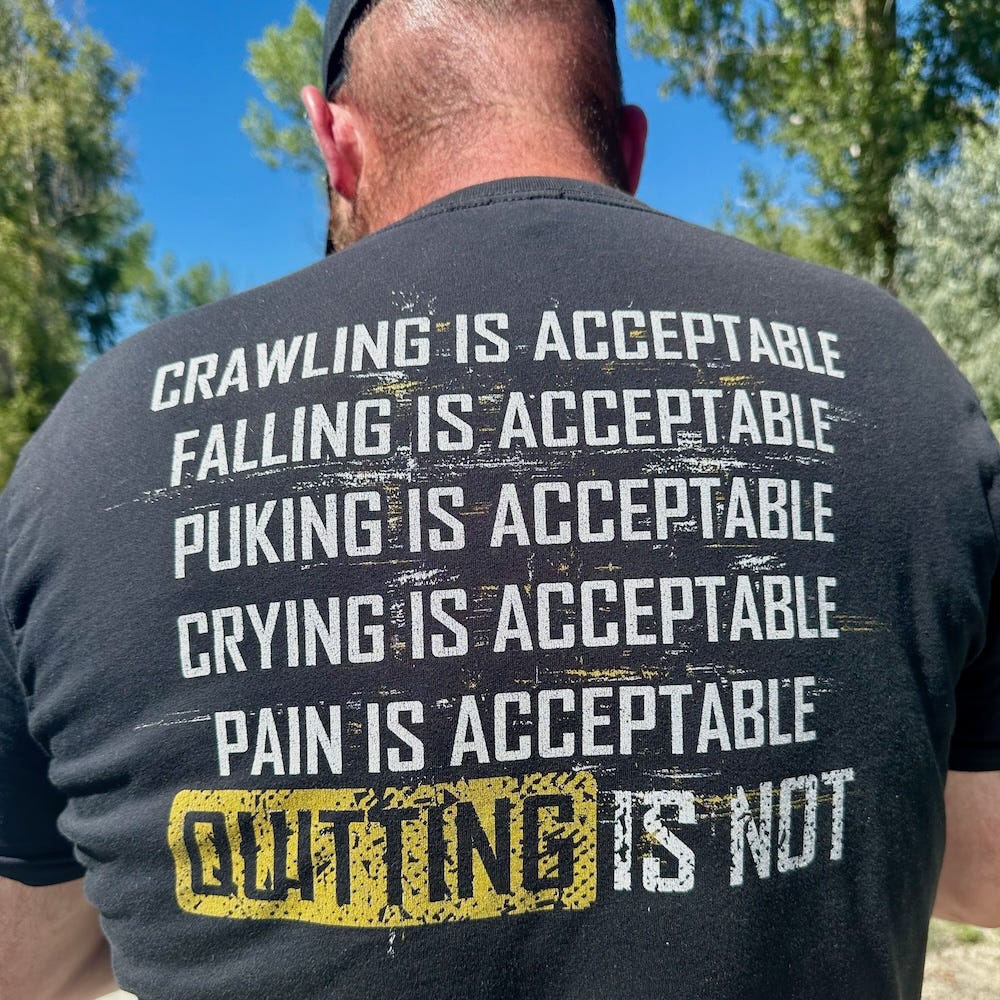

Up ahead, a heavyset sweaty man walked determinedly. As I approached him, I squinted to read all the text on the back of his shirt. What did it say about crawling and puking? I got close enough to read it fully. It said struggling—crawling, falling, puking, crying or hurting—is acceptable, but quitting is not. Yes! That shirt was a sign that I needed to finish what I set out to do.

“Perfect message on your shirt,” I said as I huffed and puffed past him.

“Damn right,” he huffed and puffed back.

The brief encounter left me electrified with motivation and camaraderie. He was just some guy, and he was just walking, but he shared this goal-oriented exercise journey on this hot day. It hit me then that the stage race may feel a bit easier than solo training runs, in spite of its length and tough conditions, because of the camaraderie and competition. The event’s daily marathon-to-50K (with an extremely hard 53-miler for Stage 3) won’t feel pointless or lonely because some 60 other crazies from around the world will share in the point-to-point weeklong journey.

I also remembered something I used to tell my coaching clients to prevent them from cutting their long training runs short: The magic happens in the final hour. You’ll want to stop when you’re fatigued, a few miles short of the planned total, but the greatest benefit from the run comes in the final hour(s) when you push past that urge to stop and develop the endurance and tenacity to get the full run done. You also may develop late-day issues such as blistering, cramping, or nausea that you don’t experience in a more manageable run, so it’s a chance to practice preventing or troubleshooting the problems that crop up in ultras.

I returned to the Walgreen’s lot 26.2 miles and some six hours after I started feeling profoundly depleted but satisfied. My watch read 5:23—a 12:20 average pace, not bad for the pack weight and walking breaks—but the elapsed time was over six hours. I had paused my watch when I took breaks to refill fluids and cool in the shade. I vowed to be more efficient and brief with stops on my final long training run and during the event’s stages.

Three days later, on Monday, I sat in my car soaking wet from an afternoon rainy run. My phone rang with a number from Vail. I answered because it might be the orthopedist office.

It was the doctor himself. MRI looks good, he said. No problem with the bone. No additional wearing down of the cartilage. Just inflammation at the IT band attachment point, which is manageable. He told me to get serious about PT but it’s OK to keep running, too.

He gave me the green light I needed to train this month with confidence. I feel like I’m building up more than breaking down. I feel like I can believe in myself again—that I can do this event one more time, in spite of being older and slower. I’ll use my age to my advantage, leveraging my experience and wisdom. And I’ll use my slow, steady, patient pace as an advantage too, like a mule passing racehorses who started the stage too fast and who wilt and fade like those sunflowers.

If you would like to support my Grand to Grand Ultra effort—and, more importantly, support and protect the public lands we’ll run through and near—please visit my fundraising page for the Conservation Lands Foundation to learn more. I’m about $1440 toward a goal of raising $5000 for this vital nonprofit.

Thoughts on trail overuse and kudos to the San Juan Mountains Association

Do you ever avoid areas because of crowds? I do. I won’t go into the town of Telluride on Bluegrass Festival weekend, for example, because it’s exasperating to navigate slow-crawling traffic and sidewalk-clogging people. But that’s just one weekend, not a big deal. What depresses and concerns me are too-crowded nature areas. Nature is supposed to be uncrowded, undeveloped, still wild—where we go to escape the crowds and noise of our cities and neighborhoods, to reconnect with a less hurried, more natural state of mind and way of being—and yet we collectively spoil it with our well-intentioned desire to go there.

You go to a trailhead and find the parking lot overflowing with cars, and then on the trail, you hear the grating voices of conversation—or worse, music playing on someone’s speaker—as you traverse the route with groups of people behind and ahead. Wildlife and birds have scattered. You spot a clump of toilet paper under a bush, or orange and banana peels on the trailside. You get stuck behind someone even though you say “excuse me, on your left” because the person’s ears are plugged with AirPods or they’re talking on their phone as they hike.

You witness some people entirely focused on capturing their selfie or drone footage, setting themselves up to appreciate the landscape more in hindsight—filtered and packaged for social media—than in the moment, and you feel hostile because you know their social media post will make this destination even more crowded. You struggle to feel peaceful and positive and to appreciate the views because you grow increasingly annoyed by those around you.

I’m writing in the second-person point of view, but maybe you don’t share this experience. Maybe it’s only my curmudgeonly hangup.

Interestingly, I don’t experience this antipathy when I run trails on the Santa Monica Mountains around Los Angeles during trips to visit extended family, because there, I’m the visitor rather than the local, and high-traffic trail use is the norm. Nobody seems to mind too much because it’s simply the way it is, given the area’s population. The mountains’ trails are like amusement parks. You get in line at the entrance and pay to park, and then you follow lines of people up and down the well-worn paths on hillsides. You get a good workout, admire the ocean views, and accept the fact that clusters of strangers are always physically near you.

When I choose to accept that fact of life in those mountains, rather than get annoyed, I can feel more neighborly and less bothered. I can smile and say hi to passersby and even, on some level, enjoy the people-watching.

But I struggle to accept the crowding here on some trails in the San Juan Mountains, and I admit to feeling more annoyed and territorial than friendly and welcoming when I hike and run some of this region’s most popular destinations. It’s not a good way to feel—it makes me feel like a grumpy selfish person.

I should be more accommodating and less resentful of the visitors who crowd the trail. I tell myself I need to share. I also need to recognize I’m one of the people contributing to the crowd. It’s like sitting in traffic thinking, “I hate traffic!” and then another voice in my head says, “You are the traffic!”

And yet—I feel sad and resentful that Instagram and trail-map apps have made certain trails’ popularity explode, along with the pandemic that prompted people to hit the road and make extended stays in remote areas.

Here’s what calms my frustration: A lot of people care and share my concern. And some are trying to do something about it and manage the situation better.

Recently, I had the chance to learn more about the nonprofit San Juan Mountains Association because I connected with the chair of its board of directors, Missy Gosney. If Missy’s name sounds familiar, it may be because she made news nine years ago with ultrarunner Anna Frost when the two incredible women became the first women to finish the Nolan’s 14 line of 14 14er summits under 60 hours.

If you live or visit here, please visit the SJMA website linked above, and/or stop by one of their 13 visitor centers in the region, to learn about all they do and about how you can reduce your impact on the backcountry. Sign up to be a member or donate to the association to support their work.

“Our big mission is to help people understand how to go into the backcountry,” Missy told me. “We do community outreach in the region to improve visitor experiences and give people opportunities to give back to their public lands.”

Missy has a deep background in environmental and outdoor education, and used to work as a high school science and math teacher. “I was a volunteer wilderness ranger as my first job, in the early ’80s, so from my background I believe we all have a responsibility for caretaking this place. … It feels as if some people aren’t stewards of the land as much as users of the land, and they have this assumption that you get to plow your way through. The courtesy isn’t there” among some trail users, she said.

I spotted a SJMA informational tent at the Ice Lakes Basin trailhead near Silverton a couple of weeks ago, when my husband and I played hooky on a less-crowded weekday to hike to Ice and Island lakes. The parking lot was full by 8 a.m. even on a weekday. I felt grateful that a SMJA volunteer was there handing out poop bags, telling people how to dispose of human waste, and giving other tips such as how to handle unpredictable weather in the high country.

Missy volunteers at this tent regularly. “Our job isn’t policing; we’re out there to help people have a positive experience and learn things,” she said. “When I volunteer up there, I try to get every person to sign in and talk to me.”

I’m trying to emulate Missy by being a trail steward who goes quietly and leaves no trace. I’m carrying extra first aid and water in case I come upon a hiker in need. I’m not sharing every beautiful photo on Instagram and geotagging it. And I’m trying to visit popular areas at less popular times to reduce crowding. I hope you might consider this, too.

Whew on the knee.

What a great account of determination and wisdom!