Summer, a Blessing and a Curse

Tensions in Telluride come to a head because we all love the place

Welcome back. Last weekend, I published a bonus post for paid subscribers and lined up a Zoom chat for us on June 14 with special guest Erica Moore, whom I profiled two weeks ago. If you’d like bonus posts and invitations to monthly online meetups, please upgrade your subscription to the supporter level.

My first races of the season are four weeks away, bunched up around the 4th of July holiday. I’ll start Independence Day with the Rundola hill climb challenge for the eighth year in a row. Most of town and its visitors charge up a ski slope under the town gondola line (hence the “Rundola” name), gaining 1800 feet in a mere 1.3 miles. The lung-burning, heart-pounding challenge is more of a community celebration of the human spirit—and for visitors, a high-altitude baptism by vert—than a race.

Four days after that, I’ll spend the weekend in Silverton for a back-to-back challenge combining the Silverton Alpine Marathon on one day with the Kendall Mountain Run 12-mile the next. I’m approaching those two events as a fun training weekend to get in better shape for the ultras I care more about in August and September.

I love summer here, in large part because of this annual cycle of building up for mountain races like these. The landscape and views of the San Juan Mountains never grow old. As long as I live here, my profound gratitude for the place and our home will not wane.

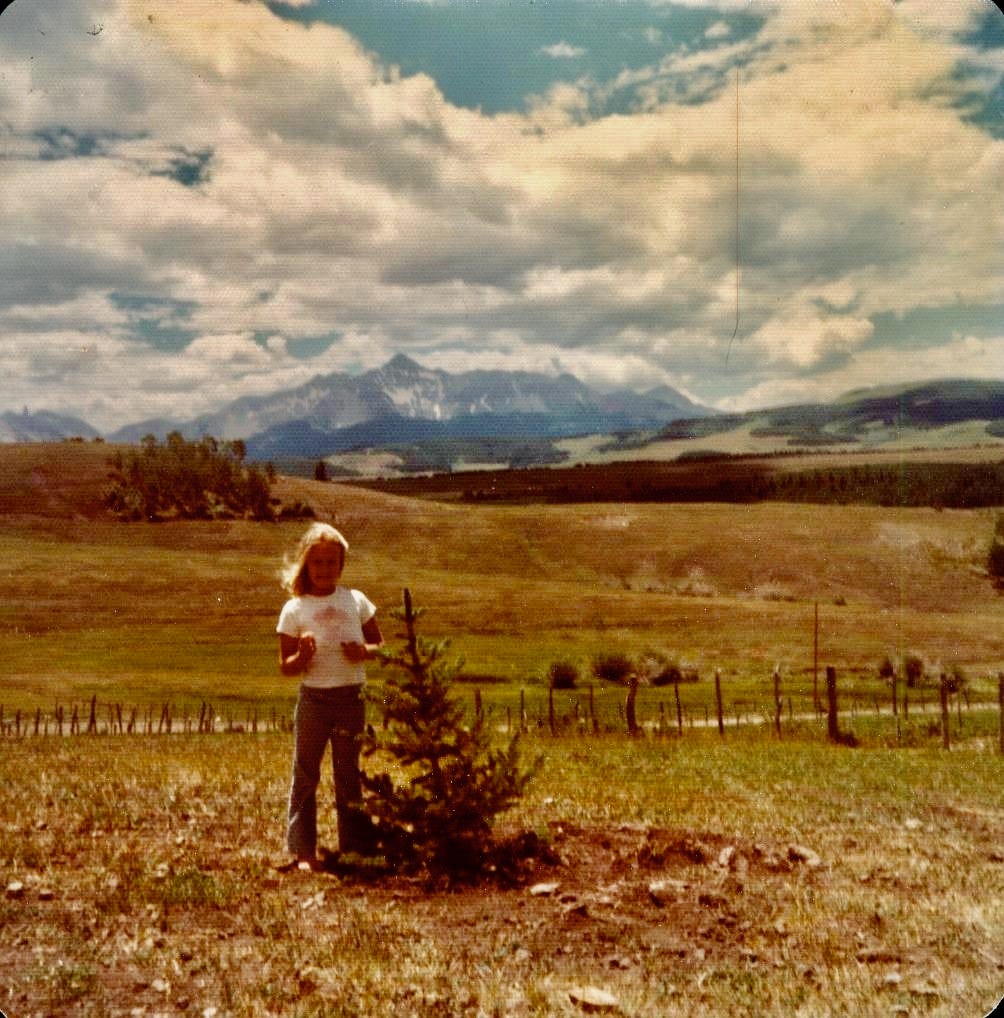

I’ll always feel the excitement I first experienced as a little kid in the mid-1970s, when I began an annual cycle of anticipating the end of the school year in Southern California so our family could come live here for three summer months. (My dad worked at a school, so he had summers mostly free, making this migration possible.) I’d ride the last stretch of the long drive from Cortez to Telluride in the cab of my dad’s truck, and as we turned the final corner that revealed the town’s box canyon, our family dog and I would stick our heads and shoulders out of the vehicle to fully take in the valley’s views and smells. I’d lean my torso out the window, fling my arms wide and yell into the wind, “We’re here, we’re here!”

As is typical for June, I’ve got summer on my mind—and that childlike feeling of anticipation—but this year, it’s cloudy, literally and metaphorically. The typically dry month is producing severe lightning and thunderstorms and dumping rain, as if the monsoon season that starts in July arrived a month early, and snow still covers high-country slopes. The upside is, the meadows are more dazzling green than they’ve been for several years, and the rivers are raging with water that’s making a dent in the chronic drought.

But summer also turns up the heat under simmering tensions in the region, which is what saddens me and clouds the bliss of this place. That’s what I want to write about this week, more than anything having to do with the privilege and escapism of mountain running.

These tensions and issues always are on my mind—always affecting the community and clouding the bucolic life and home I have here—and I struggle with what to think, do, and say. It came to a head for a few reasons this past week, one being this article in the Colorado Sun, “Colorado’s Mountain Towns Are Being Loved to Death.”

Summer in Telluride is both a blessing and a curse—a blessing for reasons and scenes described above. A curse because the vibe in town—so peaceful during April and May’s muddy off-season, when businesses and the gondola shut down for a break—turns borderline ugly due to the town’s popularity and crowding.

Restaurants set out pandemic-inspired outdoor dining areas that extend from the sidewalk past the curb, taking up scarce parking spots along the main street, and parking becomes increasingly frustrating. Tourists clog sidewalks and cluelessly stand in the middle of the main street to take selfies with the box canyon and its waterfall as the backdrop. Every other car at an overflowing parking area for a popular trailhead seems to have an out-of-state plate, and I find myself growling at all the SUVs from Texas and Arizona until I remind myself that I have Texan and Arizonan friends, and if I were them, I would want to escape their state’s heat, too.

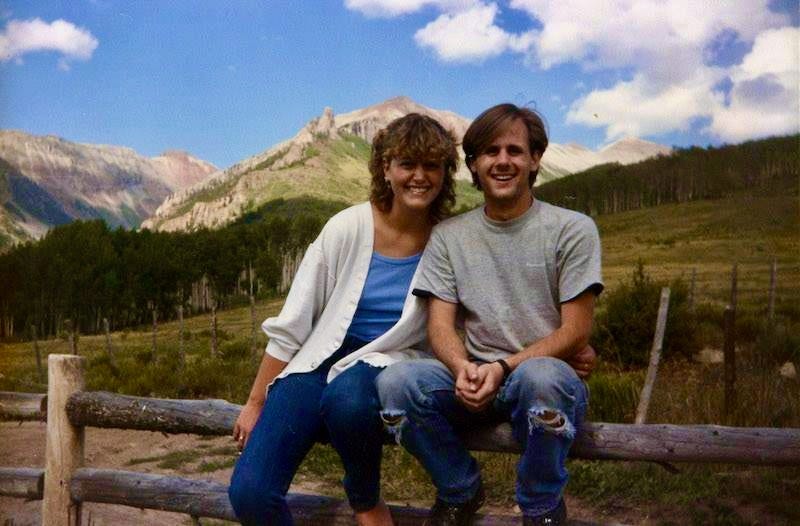

Everyone wants to find a place to park and play. And once they visit, many want to move here. I get it—I did too. Although our family roots here stretch way back, I’m fundamentally a Californian and started my relationship to Telluride as a summer-only resident through adolescence, then as a visitor for years during adulthood before we bought property in 2016 and moved here permanently.

I thought of myself as a Telluride local before we moved here, because of my parents’ long relationship with this area, but really, I wasn’t. Being a local involves committing to, getting involved with, and giving back to the place.

It seems as if everyone wants to be a local. Everyone wants to call this place home. And once they do, they don’t want it to change. But it has changed dramatically and is on the verge of developing and changing much more.

“Rants & Bitching”

Another nasty spat broke out locally a few days ago that highlights the tensions here and in small, scenic mountain towns throughout Colorado. It happened on a local Facebook page, “Telluride Sweet Rants & Bitching,” which is a cesspool of polarizing opinion. People feel emboldened to post mean and snarky comments that I doubt they would say to one another’s face.

The woman who owns a local pizza place accused another restaurant owner of “stealing” her lease when it was up for renewal by negotiating with the landlord to pay more. The other owner operates two high-quality pricey restaurants in town, and she predicted, “Our fun family restaurant will more than likely turn into another high-end overpriced restaurant.” He countered that he and his partner negotiated in good faith when the lease became available.

The post degenerated into a shrill thread of more than 80 comments that mainly have to do with the future of the town and the loss or transformation of places and businesses that give the town its character.

I know both the restaurant owners involved, and I feel for both (although I don’t know the details of what went down or anything about the plans for the pizza place’s space). The pizza place owner gave both my kids, and many other teenagers, their first summer jobs. We sometimes eat there for relatively affordable pizza because it’s casual and not impossible to get a table. The restaurant owner of the two upscale restaurants is an accomplished ultrarunner who I like to talk to about running. His restaurants are two of my favorites for a special date night. His son, and his son’s friend group, work for a locally owned, non-tourist-oriented, traditionally middle-class business—forestry management and tree clearing—and his son and other young adults like him, who grew up here, are struggling to find stable housing that they can afford.

They’re all locals. They all seem like good people. They’re all struggling on some level to make a living and to sustain their businesses. And yet, this comment thread quickly turned nasty and impassioned—local-on-local, splitting the community—because most people who live and work here feel threatened.

So many people I know here share a common feeling that their livelihood, housing, the town itself, and the surroundings—the beautiful, mountainous natural environment that drive so many to visit and want to move here—are threatened by growth and crowding, income disparity, and a squeezing out of the town’s non-millionaire workers who keep the tourism-based economy running.

On Monday night, I went out with a friend who’s a dentist and manages a local dentistry, and she was utterly stressed out because she had to start sharing her rental with an employee and that person’s dog because the employee lost her housing, and her dentistry business will cease to function if that worker moves away. “I haven’t had a roommate since college,” she said, on the verge of crying.

Regional growing pains intensified, and the gap between have’s and have-not’s widened, during the pandemic. A wave of wealthy professionals, generally from the East and West coasts, discovered they could work remotely, so they moved here or bought a place as a second home, driving up home prices dramatically. As this article details, the amount spent on real estate in six Colorado resort-oriented counties (including where we live, San Miguel County), more than doubled between 2019 and 2021.

My husband and I recognize how fortunate we were in terms of timing to buy property, build a house, and move here when we did. We leveraged all our resources and took out a ginormous mortgage to make it happen. Given how real estate and home-building costs skyrocketed, it’s doubtful we could have or would have made it happen if we waited until 2020.

It’s easy to demonize the pandemic transplants, but those I’ve gotten to know—like the affluent couple from DC whom I met through a mutual friend—are at least trying to give back to the community in some ways. The man from DC, for example, started a music show on the local radio station and is running for elected office in Mountain Village (the resort town above Telluride), literally knocking on doors to meet residents and hear their ideas about how to face tough local issues.

The point is, people are basically good and well-intentioned, because they love this place. There are just too many people.

I will point my finger with resentment, however, at the proliferating high-fashion businesses that cater to the uber-wealthy tourists and residents. I never step foot in them, because each piece of clothing or knick-knack costs several hundreds to thousands of dollars, and no real person I know and like buys or wears that kind of stuff. If some of those nauseatingly expensive boutiques go out of business because they can’t find staff to hire, then I say good riddance. I won’t care about the potential loss of that type of business the way I care about my friend the dentist potentially losing her livelihood.

And yet, in the next breath, I must admit the irony, complexity, and borderline hypocrisy of my judgmental statement above. There is one high-end boutique I step into, not to shop, but to admire with pride and love one of their ridiculously priced items. This boutique sells gorgeous designer handbags—handbags designed by my talented daughter in California. The company that employs my daughter as their designer exists because luxury shops like this one in Telluride and their customers exist.

And my son has a summer job in northern Colorado working with horses and guiding guests on an exclusive dude ranch because affluent tourists exist who want an authentic ranch experience.

Everything feels complicated and interconnected. And I don’t think any clear, easy solutions to the town’s tensions and growing pains exist.

Telluride is on the verge of becoming another overbuilt ski area—and given all the development projects in the pipeline, such as new hotels and a medical center, it may have already tipped past what’s termed the “carrying capacity,” which refers to the ability to serve the community with water, wastewater treatment, fire protection, public schools, and the like. The geographic barriers of the town’s mountain slopes, and a commitment to protect the beautiful, elk-filled Valley Floor at the town’s entrance as open space, have created pressure for sprawling leapfrog development on county land skirting town, including open space zoned Forestry/Agriculture near where I live.

I took heat last year as a “NIMBY” for opposing an ill-conceived and rushed plan to plop down a new neighborhood of hundreds of high-density homes on a scenic open mesa a half-mile from our home, and more than five miles from town. I won’t get into the details here, but I went out on a limb and wrote this guest editorial in the local paper explaining my view if you’re interested.

I believe we can’t grow our way out of the problems facing Telluride, or we’ll ruin what we love about this place. The harsh truth is that not everyone who wants to live here can; and, not every shop and cafe need to thrive, not every hotel needs to be built. Much-needed housing for essential workers—deed-restricted and priced for local workers to rent or buy—should be built on parcels close to existing infrastructure and water, and close to town to minimize the traffic to town. Those parcels exist, but each one is complicated, and it will take political will, wisdom, dialogue, and compromise to make smart housing happen.

I try to do what I can to help and preserve this community. I’ve led a local nonprofit service organization, and I started substitute teaching in the local schools, for example. I’m beginning to study and plan what it’d take to build an auxiliary dwelling unit to rent to a local. I stay informed about regional issues and try to get people who have opposing views to talk rather than avoid each other.

But it’s so painful and tense at times, especially during summer and winter peak tourist seasons. And that’s part of what makes locals locals—we’re in the thick of the thorny issues. We’re past the initial phase of awe and romanticism that everyone here experiences when first visiting or relocating. We struggle with impending change and loss, and argue about how best to manage it.

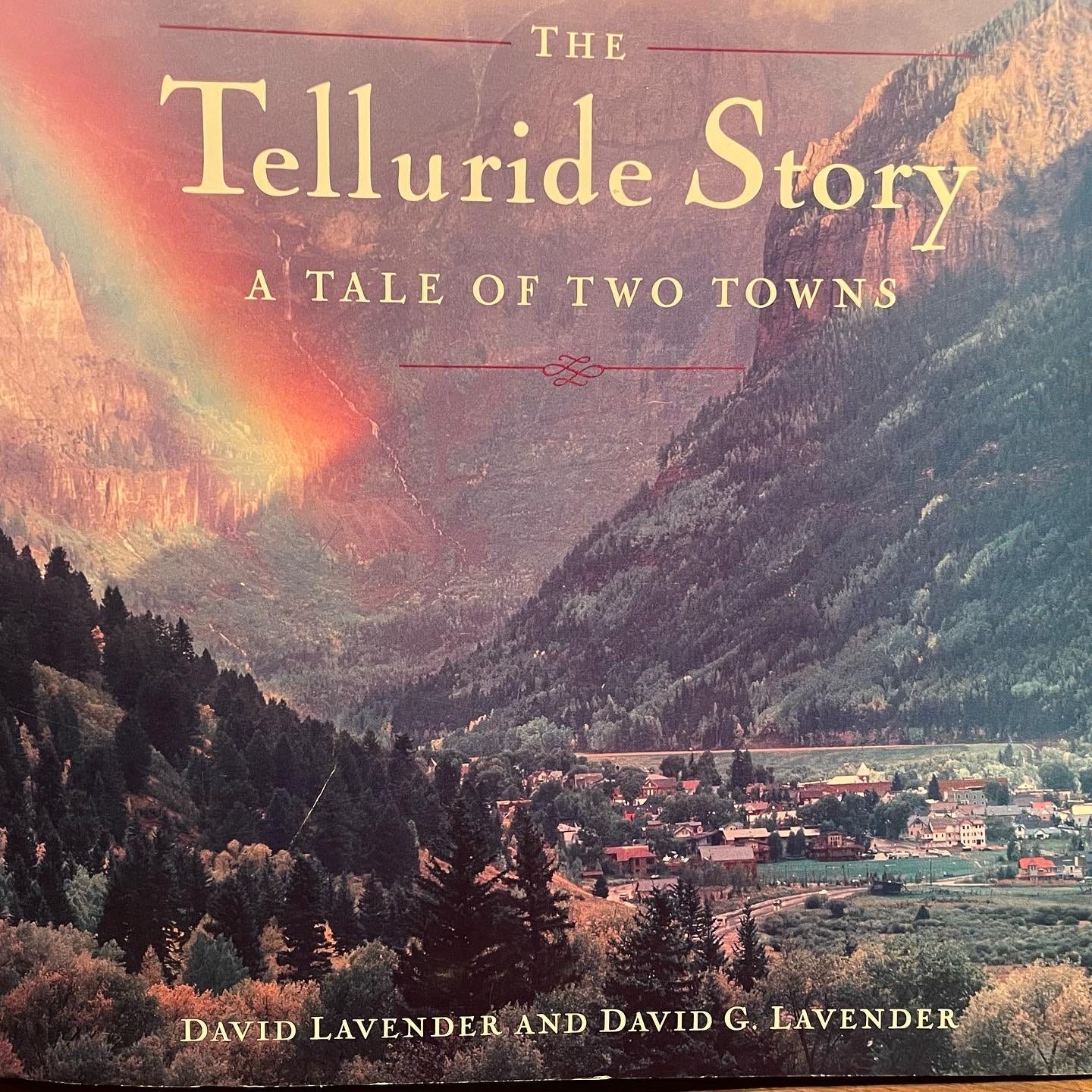

There’s nothing really new about this Telluride story—rather, it’s a new chapter in an ongoing story. My grandpa and dad wrote earlier versions of it and even titled it “The Telluride Story.”

My grandfather is the historian David S. Lavender, born and raised in Telluride, grandson of the town’s first mayor. He wrote several books about this region and the West’s history and its boom-and-bust cycles. My dad, David G. Lavender, updated Grandpa’s 1987 edition of “The Telluride Story” in 2007, adding a chapter about the emergence of Mountain Village and the fight to preserve the Valley Floor. He detailed the town’s growing pains that continue now, and he even foreshadowed the threat of climate change and how snow and water scarcity could doom the town’s economy.

My dad, who died in 2013 and is buried in the town cemetery, ended with a call for preservation in his penultimate paragraph. He imagined Telluride in 20 years, which would be 2027, and hoped that “limited space for further construction will have kept change to a minimum. On the other hand, a bleaker scenario could unfold. Considerable diligence will be required to ensure that low-density zoning laws and preservation of open space continue as priorities. Otherwise, a new generation of developers might someday undo all that so many have worked to preserve.”

As our community grapples with a new phase of master planning that charts the region’s future, I’ll keep my dad’s words in mind. I’ll also keep my friends who cope with housing insecurity in mind.

I’ll try to keep an open mind, stay involved, and help where possible, because I want to and have to—because that’s the responsibility and reality that come with living here.

This post was inspired in part by a post I read last week by

called “Hometown’s Finest.” She asked her readers: “What’s the best place in your past or present town or neighborhood? What, exactly, gives it its placeness? (You can also eulogize places that are no longer here, but I especially want to hear about ones that are still here).”I could have commented on several places in Telluride—such as Timberline Hardware, Between the Covers, Telluride Toggery, the Floradora Saloon, Baked in Telluride, or the Sawpit Store—and perhaps I will, in a future post here. Instead, I wrote this on her comment thread, about the place I mainly grew up, Ojai. I share it here because it relates to the pangs I feel now about Telluride.

Rains department store of Ojai, California. Maybe you know Ojai as a day-trip destination or bedroom community for affluent Los Angelenos. I know it as the once-middle-class hometown where I grew up on an avocado orchard, and where my mom and her friends opened a children's book and clothing store from the 1980s through mid-'90s until high rents in the town's mission-style Arcade shopping strip turned all of the regular-folk shops into galleries and designer boutiques. But Rains lives on. It's a true general store. You can go in there and buy earrings, underwear, potholders, and gardening tools. I can actually leave the store with a new, not-too-pricey blouse folded in a bag in one hand, and a broom or rake in the other. The last time I stopped in there, the older lady at the register said she remembers when my big sister worked at Rains in the '90s. I feel pangs of nostalgia and sadness when I return to Ojai, because its main street is choked with traffic and I don't recognize the people or most of the businesses—except for Rains. Thank god, Rains is still there, which means it's still the place I grew up.

Related posts:

Ups & Downs (about why mental health is vulnerable in mountain towns)

Digging Into the San Juan Mountains (a brief history of the region)

Sarah, did you read the article from the NYT Sunday Magazine on housing issues in Berkeley? The issues are similar. I think you’d appreciate the piece. The author did a good job grappling with both sides of the issue, as you’ve done here. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/30/magazine/housing-berkeley-yimby-fight.html

Don Henley lyrics in “The Last Resort.” Nuff said.

Good piece Sarah. I spent part of the 80s and all of the 90s in Vail (snarkily known as a wide spot in Interstate 70), and it has seen a similar fate)