Run to Remember, Not Forget

Reflections on the pandemic five-year anniversary, body image, and influencers

Don’t forget or take it for granted

As I get back to training post injury, rebuilding a base of 40-to-50-mile weeks with strength and mobility sessions in the mix, I challenge myself not to take the injury-free healthy feeling for granted.

Don’t forget, I tell myself, how desperate I felt from November to January when I could not walk without pain and limping. Don’t lose the joy, I also remind myself, that comes from being able to act like an athlete again in the company others, as I did two weeks ago at that running camp or last Friday at a silly kickass winter hill-climb race up a ski slope. Don’t fall back into approaching training like a chore, because it’s a privilege.

This past week delivered a couple of powerful reminders of that don’t-take-for-granted message. First, I talked to my daughter, who’s trying to regain normal weight-bearing walking on her left leg following surgery for a ski accident two months ago. The physical struggle creates mental struggle, and she feels stuck literally and metaphorically. As a mother, I’ve always felt that “you can’t be happy unless your kids are happy and healthy,” and her recovery tugs at my heart. I have faith she’ll get better and back to her active self, but meanwhile, I want to wave a wand to make her physical limitation disappear.

Also, I found myself dwelling on the fifth anniversary of the pandemic. In March of 2020, everything changed in our household as both kids moved home from college, my husband Morgan’s business shut down because the courts closed (he runs a firm that specializes in litigation graphics and trial prep), and we all caught early cases of the new, scary coronavirus toward the end of that month (we suspect because our son brought it home with him after attending the X-Games in Vail, which probably was an early super-spreader). While my kids and I recovered, Morgan got worse.

I will never—and should never—forget the night and daybreak morning in late March of 2020 when I drove him to the local ER because he was incoherent with a fever of 103 and grayish skin. The oxygen monitor showed his level had dropped to 74, indicating severe hypoxia, and a CT scan showed the dreaded ground-glass pattern in both lungs characteristic of bilateral viral pneumonia. The doctor told me I had to take him to the regional hospital 60 miles away in Montrose for treatment, because our local medical center was not equipped for overnight patients with covid.

I drove us back home around 3 a.m. to pack a bag and to wake up the kids to say goodbye to their dad, wondering if it would be the last time they would see him. Remember, this was at a time when the news showed temporary morgues on trucks parked outside of hospitals in NYC and reported on patients dying alone on ventilators.

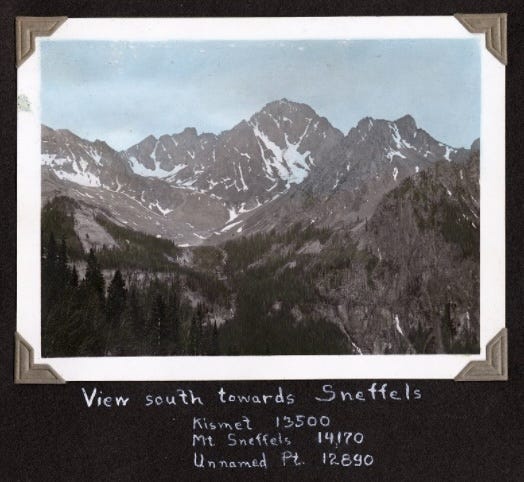

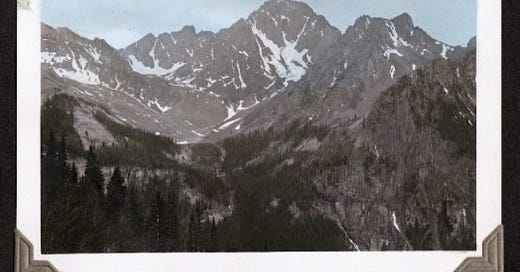

I drove him to the hospital and said a tearful, rushed goodbye in the parking lot, because I was not allowed to accompany him into the hospital. Then on the drive home, as the sun rose on the summit of the 14’er Sneffels, I pulled over to the side of the highway because I was sobbing too hard to drive as the possibility of losing my husband—with whom I fell in love at age 15—hit, and I faced the fear of living without him.

What’s more, the stunningly beautiful view of the Sneffels mountain range at sunrise hit me emotionally at that moment because it made me think of my great-uncle, Dwight Lavender, who was a famous mountaineer in the late 1920s and early ’30s and spent the majority of his time on Sneffels logging first ascents, mapping, and building a high-country hut. In the fall of 1934 at age 23, Dwight went to Palo Alto for graduate study at Stanford, caught the polio virus because at that time no vaccine existed for polio, and within 72 hours his athletic body succumbed to infantile paralysis as the virus killed him.

I am the club president for our local Rotary Club, and Rotary International has been a global leader in polio eradication and other disease prevention through vaccines, sanitation and clean water projects, and other public health measures. I think of my great-uncle Dwight’s rapid death from polio when I renew my support for Rotary’s efforts to fight disease. Among the many things that infuriate me about the new administration’s radical hatchet job on institutions, employees, and America’s alliances in the world, I’m extremely alarmed about the politicization of disease prevention, which makes polio, HIV, TB, measles and other horrible but preventable illnesses poised for a resurgence because of the cutback in foreign aid and the spread of misinformation and fear around vaccines, especially with RFK as the new HHS secretary. 1

My husband recovered from covid after intense oxygen therapy and antibiotics, and he was on supplemental oxygen for a month but eventually got back to normal. I don’t ever want to forget how fearful that time was, because then I might take for granted our health and the heroes of medical care and science.

This weekend, I’ll go to Moab and run a desert trail race—“just” a 30K (19ish miles)—as part of my buildup and comeback. I still have a lingering appreciation for gathering elbow to elbow with others, no masks, after living through all the event shutdowns five years ago. I vow not to lose that appreciation, nor to forget how fortunate I am to run again.

For further reading, I recommend this powerful essay by

, an avid outdoorsman coping with long covid:And for more pandemic reflections, I offer this post I wrote about the crazy circumstances of March 2020, when on top of everything else changing that month, a horse luckily came into our lives.

Unfollow those who make you feel bad

I listened to an important podcast last week on body image, and it prompted me to clean out my Instagram feed by unfollowing several influencers whose show-offy and likely filtered posts trigger me to feel inwardly bad or insecure about my image and/or athletic performance.

The podcast was Your Diet Sucks with the sports nutritionist Kylee Van Horn and journalist Zoe Rom, both of whom I admire, and the episode was, “Body Image Bullsh*t, Fitness Culture, and Athletes.” The intro summarizes the topic: “What happens when the pressure to perform collides with the pressure to look a certain way? This week, we’re tackling body image in sports and fitness, breaking down the differences between body dysmorphia, body dissatisfaction, and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD), and why athletes are especially vulnerable.” I recommend listening to it here.

Body image is a “running” (pun intended) theme in my memoir in progress, which in a nutshell is about my journey through a weeklong extreme ultramarathon that helped me realize I don’t have to run from my past or prove myself anymore. Running became a way to work through shame and regret and to finally feel good about my body and choices.

In flashback chapters to childhood and adolescence, I share stories about being over-sexualized and promiscuous from a young age due to my parents, my birth order (youngest with four much older siblings), and the era. I underwent an ugly-duckling transformation that made me hyper concerned with appearance, followed by a period when I became nonconformist, used drugs heavily, and engaged in other risky behavior as a reaction to that early conditioning to put out and be pretty. Those experiences fed into me becoming the ultrarunner I am. That’s a roundabout way of saying that discussions of “body dissatisfaction,” like the smart one on that podcast, resonate, since I’ve spent the second half of my life working to feel strong, confident, and good in this body.

Last week, after listening to that podcast, I unfollowed female athlete-influencers in my Instagram feed who trigger self-doubt rather than positivity about aging, appearance, and performance. I’m choosing to follow instead those women who are keeping it real (e.g. showing wrinkles on their forehead and/or rolls above their waistband), who keep their humble-brag posts to a minimum, who do not look thin to the point of unrealistic or unhealthy, and who have meaningful and humorous things to share. And pets—I’m a sucker for pet posts!

Meanwhile, I’m also following more environmental-conservation activists (like this one and this one) and those who simply make me feel good and inspired (like this one). And in general, I’m spending less time on social media, really only on Instagram and Substack’s Notes (I don’t bother with X, Bluesky, or TikTok, and I’m minimally on Facebook to check in with old friends and some family members).

It’s a simple thing, but I’ve noticed in recent days it has made a positive difference in feelings and body image when I scroll. Try it, clean out your feed!

I also recommend this other episode on the Your Diet Sucks podcast, in which the hosts take a deep dive into Robert F. Kennedy’s background and the politics and culture behind the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

Please let me know if you liked this post by leaving a “like” in the heart below. And I encourage your feedback in the comments!

I’m with you on the “don’t follow people who make you feel bad!” And I hope people understand it’s not personal either - it’s my own triggers. Sometimes they are friends in real life, just can’t deal with the social media presence. It’s a weird world.

You nearly lost your husband! Sent away from the E.R. to drive 60 miles in the mountains, and he had an oxygen saturation level of 74! Yes, it is important to be grateful for science, modern medicine, and vaccines. Once again, stellar writing Sarah.