Heating Up

Last weekend, while visiting Boulder, I ran a 22-mile route through open space on the west side of the town with a climate and terrain much different than what I’m used to in the higher-elevation San Juan Mountains. Everything feels hotter and drier on the Front Range. The tall grass had yellowed, and the breeze felt as warm as a hair dryer.

Even though I had loaded my pack with four 17-ounce soft flasks of fluid with an electrolyte mix, plus a 24-ounce plastic Gatorade bottle repurposed to carry water, I realized three hours into the run that I would run out and would need to detour to a neighborhood to refill.

Overheating and dehydrating are two of my biggest concerns and precautions. I’ve been in hot races and training runs before where I’ve flirted with signs of heat exhaustion (the first phase of heat illness that can progress to deadly heat stroke). For example, in a 2017 self-supported stage race on the Big Island, called the Mauna to Mauna, I ran out of water as the route transitioned to the hottest part of the island on the Kona side. My skin, no longer able to sweat, felt prickly and dry. My vision blurred and looked wavy. My head throbbed against my hatband. I distinctly remember thinking, “This could end badly.” Since running increased my stress, I focused on hiking and taking calm, steady breaths. I finally made it to a checkpoint to rehydrate and took extra time in the shade to cool.

With seven weeks left until the Grand to Grand Ultra desert race, the Boulder run was a reality check that I need to do more to prepare and acclimate for the desert conditions, where temperatures on the wide-open plateaus can easily reach the 100s and where the light-colored sand reflects heat and makes it feel even hotter. So for this post, I’ll share some tips about heat acclimation.

In Boulder, the temps during my run reached “only” the low 90s, although the weather app said the “real feel” was about 100. For me, not well heat-adapted, anything over 80 feels hot. As I ran, I started to sense some warning signs of overheating: insatiable thirst even though I was regularly sipping; elevated heart rate that stayed high even with hiking breaks (my heart rate was much higher than it should’ve been—in the high 130s instead of mid to low 120s—given my slow, easy pace); and dry, flushed skin that was losing its ability to sweat. When I thought about eating the bar I brought for a snack, my tastebuds and stomach said no, so I didn’t eat.

It’s helpful to understand why running in the heat is so challenging and dangerous. Basically, you’re stressing your body by asking it to do more. Blood gets diverted from your working muscles and from your gut to flow toward your skin for the all-important job of dilating blood vessels and dissipating heat. The blood flow also triggers sweat glands to sweat and cool your skin.

When your body’s blood flow prioritizes thermoregulation through your skin, then you’re at risk for both fatigue and nausea because blood flow to your muscles and gut becomes strained.

Thankfully, I only had to detour about a mile into a North Boulder neighborhood to find an air-conditioned cafe. I paused my watch and spent a good half hour in there. First I went to the bathroom and used water to cool off my arms and face, and to dampen the bandana around my neck. Then I sat in the cool indoor air until my stomach settled and I could enjoy a croissant, La Croix, and ginger ale. Refreshed, I finished the five-hour run.

Of course, an air-conditioned cafe with cold drinks won’t be available during the self-supported 170-mile stage race, which follows a route from northern Arizona to southern Utah through very remote and hot regions. Because the race is self-supported—meaning, we carry all of our food and gear in backpacks for the week—the checkpoints offer only water and a little bit of shade from a pop-up tent. No ice, no aid station goodies. And the water is limited, so we can’t use it to pour over our skin or to wet our clothes.

What to do, then, to prevent and troubleshoot overheating?

The first line of defense is to get as fit as possible, so that your cardiovascular system is optimized to function well with the added stress of running in the heat. I’m fortunate to live at high altitude (9000 feet), which likely means my body has adapted to produce more red blood cells and more plasma volume, which should help. On the other hand, I’m older (55), so my body’s oxygen-carrying capacity has declined naturally with age. Even though I’ll run and hike at a very slow pace at the Grand to Grand Ultra—given the climate, the weight of my pack, and the challenge of running in sand—I’ve tried to keep up weekly speed work in training, not to get faster, but rather to elevate my heart rate and maintain cardio fitness.

To prepare specifically for hot-temp races, you should heat train, which provokes the body to adapt to sweat earlier and more and to better tolerate the discomfort. But how? Jason Koop has written about research into heat training and explains recommended protocols better than I could, so check out his article or his Training Essentials for Ultrarunning, Second Edition book for an overview.

The good news is, a little goes a long way; meaning, it doesn’t take a great deal of heat exposure to elicit a positive adaptation, just 60 to 90 minutes at a time for about seven to ten days. As Koop notes, “Acclimation to heat stress is an acute adaption. Once you are exposed to heat, it takes days, not weeks to achieve a robust response.”

In hindsight, I made a risky mistake last Sunday jumping into a five-hour run in the heat, not well adapted, when I could have had a higher-quality long run—with more steady running and fewer hiking breaks—in cooler early-morning temps, saving the hot portion of it for the final hour.

For the Grand to Grand Ultra, I’ll take a two-phase heat-acclimating approach by doing a limited amount of my peak training this month in hot temps. I have to be careful, because I’m also adding stress to my body by training with pack weight and increasing overall volume. Therefore, I’ll try to concentrate the heat-training runs in one week mid-August when my overall volume is lower. I’ll drive to the region around Montrose, where it’s much hotter, and do runs lasting about 90 minutes to two hours in the heat and work up to one longer run in the heat.

Then, ten days leading up to the Grand to Grand when I’m tapering, I’ll do some form of heat adaptation every day. I’ll run in the heat for about 60 to 90 minutes, followed immediately by more heat exposure in a hot bath at home. I’ll reduce my running significantly in the few days before the race starts to optimize rest, but I’ll be in the hot climate of Kanab, Utah, so I’ll simply take midday walks in that heat to get used to it.

The other essential precaution for running in the heat involves being smart about hydration and electrolytes. Take more fluids than you think you’ll need, and use a hydration mix to replace the salt you lose through sweating. Personally, I like a low-calorie mix (such as Scratch) that provides ample electrolytes (400mg sodium per serving plus some potassium and magnesium) and just a little bit of sugar (80 calories) to aid in the gut absorption. In regular mountain conditions, I normally use this at half-strength (because I just don’t need that much salt in cooler temps), but in the desert I’ll use it full strength. Additionally, I’ll have one bottle with higher-calorie mix (such as Tailwind or GU Rocktane) because it’s difficult to chew, swallow, and digest solid food in hot, dry conditions, so I prefer most calories to be liquid while I’m on the trail.

When you feel yourself starting to overheat on the run, try to relax and go easier. The more you can moderate your effort level and stay calm rather than anxious, the better you’ll be able to handle the stress. Prepare to go slowly (so budget extra time) and take hiking breaks as necessary to reduce the exertion.

Mostly importantly, be aware rather than in denial of warning signs that you’re getting dangerously hot. It’s one thing to think, “I’m really warm and need to slow down,” which is fine and normal. It’s a more dangerous thing to feel spacey, lightheaded, mildly confused about time and direction, and sleepy. Worse, your vision can start to get wavy or blurry, your heart can start racing, and your skin can strangely become pale and cool or clammy. If you start to feel that way in the heat, it’s imperative to get in shade, cool off, and call for help.

Finally, don’t overlook the importance of sun protection. I use a wide-brim river hat to shade my neck. I also started using a cotton bandana tied around my neck, rather than a buff, because it’s easier to untie it and dip it in creek water and then retie it, rather than pulling a buff off my head. The cotton retains water longer, too. (Thanks to Yitka for this tip, which she gave me during Hardrock!) I know a lot of people recommend sun sleeves, but frankly, they bug me and heat up my arms. Sleeves can be great if you can wet them and fill them with ice, but that won’t be an option for me during the Grand to Grand, so I’ll use extra sunscreen on my arms and hands instead.

Please share your heat-training and cooling tips in the comments below!

As I wrote last week, I’ve launched a fundraiser to support Conservation Lands Foundation and to raise awareness about public lands protection around the Grand to Grand Ultra’s route. I hope you will visit my fundraiser page here and consider a donation!

Many thanks to the seven donors so far who have given a total of $545. I’m a little more than one-tenth of the way to my goal of raising $5000.

Here’s another installment about the foundation’s work to protect and enhance the public land managed by the Bureau of Lands Management.

What is a National Monument and why should you care?

When you hear the word “monument,” you may think of a statue or a building with a plaque commemorating its history. A few monuments, including the Statue of Liberty, are this kind of “monument” and have been given the special designation of “National Monument” to protect them.

But I’m going to talk about a completely different kind of “monument”—a large area of public land and its waterways designated for conservation.

These National Monuments are controversial, opposed by some for myriad reasons including the desire to keep using the land without future restrictions on mining, drilling, or other uses, and also opposed by those who resent federal power over local or state control. I hope to show you why I support National Monuments and the role they plan in wildlife protection, climate resiliency, and preserving history and culture.

National Monuments are one designation of public land that make up the National Conservation Lands; others include National Conservation Areas, Wilderness Study Areas, Wild & Scenic Rivers, and National Scenic & Historic Trails. The Conservation Lands Foundation advocates for all these designations, and for a network of locally based environmental groups that steward specific parts of the National Conservation Lands; learn more here.

The Grand to Grand Ultra starts in one of the country’s newest National Monuments, on the north edge of the Grand Canyon National Park. It’s called “Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni—Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument”, designated by President Biden on August 8, 2023. The Conservation Lands Foundation was a strong advocate for it, as their Instagram post indicates:

The presidential proclamation explains the need for and significance of this area in part:

“The lands outside of the national park contain myriad sensitive and distinctive resources that contribute to the Grand Canyon region’s renown. In many of these lands outside of the national park, however, the Federal Government permitted or encouraged intensive resource exploration and extraction to meet the needs of the nuclear age. For decades, the Tribal Nations and Indigenous peoples of the Grand Canyon region have worked to protect the health and wellness of their people and the lands, waters, and cultural resources of the region from the effects of this development, including by cleaning up the abandoned mines and related pollution that has been left behind. … Protecting the areas to the northeast, northwest, and south of the Grand Canyon will preserve an important spiritual, cultural, prehistoric, and historic legacy; maintain a diverse array of natural and scientific resources; and help ensure that the prehistoric, historic, and scientific value of the areas endures for the benefit of all Americans.”

The Grand to Grand route also runs past the beautiful Vermillion Cliffs National Monument and ends near the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, a massive geologic formation that’s home to an abundance of Native American cultural sites and dinosaur fossils. Its boundaries have been under attack—scaled back under Trump, then restored by the Biden administration—and the Conservation Lands Foundation has prioritized defending its boundaries.

In most cases, National Monuments are created by proclamation of the executive branch under the Antiquities Act. President Theodore Roosevelt signed the Antiquities Act into law on June 8, 1906, to protect significant natural, cultural, and historic sites. At the time, looting and vandalism of archeological sites, especially for Native American artifacts, was common.

National Parks, by contrast, are established by Congress. Roosevelt established the Grand Canyon as a National Monument in 1908, and nine years later, Congress made it a National Park.

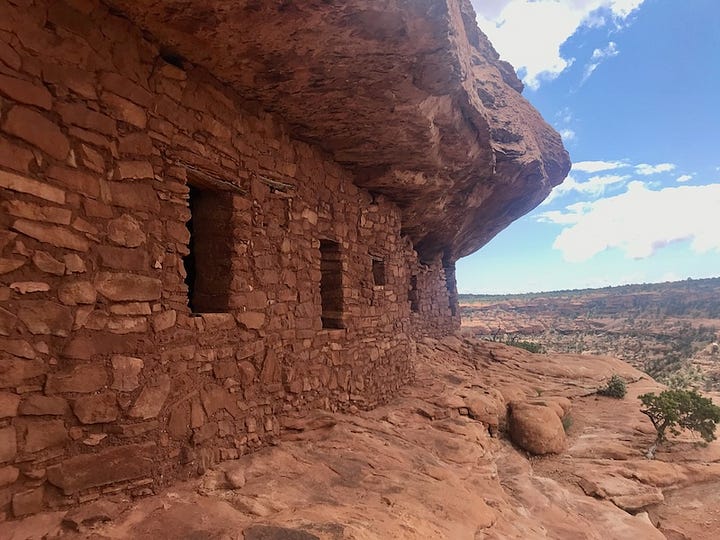

National Parks also differ from National Monuments in that the National Parks tend to have more infrastructure for visitors, whereas National Monuments tend to be less developed and generally less visited, something I observed firsthand when I compared a visit to Mesa Verde National Park with a trip to Bears Ears National Monument. Mesa Verde is marked by a network of asphalt paths and roads, a massive visitor center, and crowds so heavy that reservations are needed to visit certain sites of the Ancestral Puebloan dwellings. By contrast, Bears Ears has minimal infrastructure, and hiking its trails feels quite remote.

What, exactly, does a National Monument designation do? Generally speaking, it grants special protection to land already owned by the federal government (which is why it’s misleading for opponents to call it a “federal land grab”). It creates a resource management plan involving all stakeholders, so it sets up a process to steward and preserve the land in a collaborative way. Then—most controversial—it prohibits future mining claims and leases for energy development. Existing valid mining and drilling claims are respected, as are existing grazing rights and most recreational uses, but it grandfathers out future extractive uses. In my view, this is an important and necessary conservation step to slow climate change and protect the areas’ ecosystems and biodiversity.

The Antiquities Act is under attack by conservatives who’d like to abolish it and see any protection for public lands go through Congress or state legislatures. Congress does, in fact, have the power to designate public land as “National Conservation Areas,” which leads to much the same protection as a National Monument. But with Congress as gridlocked and polarized as it is, this legislation currently has little hope of becoming a reality. National Monument designation therefore has become a more important and effective avenue for protecting federally owned land from future development.

For the past several months, I’ve witnessed up close the fight over National Monument designation play out in the Dolores River Canyon area west of where I live, near the Utah border. It’s been fascinating and difficult to observe, as I sympathize with many opponents’ fears of too many tourists changing their communities; they also fear losing their ability to mine the land in the future for uranium. But I still favor monument designation to protect the watershed’s waterway and wildlife, and to plan for its future in a proactive rather than reactive way.

For an excellent article on the complexities, history, and politics of the Dolores Canyon controversy—which mirrors the issues around National Monuments in general—read

’s latest post:Please join me in supporting the Conservation Lands Foundation’s important advocacy and their support of a network of grassroots groups working on behalf of these threatened public lands. Click on this button:

Thank you so much for reading this far! I’d love to read your heat-training and cooling tips or experiences in the comments below.

When I trained for desert rats Kokopelli I started heat training by doing short loops with my car as an aid station. As I became better heat adapted I lengthened the loops. This progression helped me feel safe and less anxious while training in over 100 degree temps. Shit goes wrong fast out there.

Second all of that, Sarah. I did the Grand Canyon Rim to Rim a few months ago. We ran out of water during the hottest part, so we had to muscle out a long 5 miles before the next rest stop. I regulate my breathing, first. Then, I focus on each breath, which focuses my mind. I become hyper aware of each thought, ensuring that it's positive or helpful. The last thing I want in that situation is to panic or start focusing on thing I can't control.