How to Handle a Run-Stopping Injury

Get the care you need & address biomechanics for starters

Welcome back, and welcome new subscribers. Next week, on November 21, I host the monthly online meetup for paid subscribers. If you’d like an invitation to the monthly Zoom, along with occasional bonus posts (like this one from last week), please consider upgrading your subscription to the supporter level.

Today’s post is about coping with run-stopping injuries and making an action plan to get better. Why? Because I’m injured.

As described in last week’s post, I ran well for 50ish miles of an ultra on November 2 and then went 12 more miles mostly walking and limping. I wasn’t entirely sure what I was dealing with—whether it was tendonitis flareup of the IT band, or something worse, like a tear of the tendon attachment and possibly a reaction on the bone. A big bruise-like spot on the painful area came from internal stress, not from external trauma, and suggested something very wrong happened under the skin, perhaps internal bleeding or bruising.

At this point, I could draw and belabor parallels between my pre- and post-injury state of running and my pre- and post-election state of mind, from optimism and wishful thinking that ignored underlying problems, to pain and confusion, to denial and dismay, to resignation and acceptance, to determination to understand and get better, but I’ll spare you!

The mental shift, however—from denial and despair, to acceptance, understanding, and determination—is key for injury recovery. The best injury advice I ever got and used to share with injured clients when I coached was: transfer all the energy and focus you devote to training to recovery. Be the best patient you can be. Make injury recovery your project for now.

I hobbled around post-ultra for several days in a painful daze, an ice pack stuck to my left knee with an ace bandage wrapped around it. I thought it would get better, as it usually does. Four days later, it still hurt enough to make me wince going up and down stairs, no improvement. The “hop-on-one-foot test” would trigger shooting pain. (A rule of thumb is, you should be able to hop on each foot pain-free following injury before returning to running.) I’m fucked, I thought.

No, I’m injured.

A switch flipped in my brain, the one that activates project management for coping with bad news or bad outcomes. With this change in mindset, I could own this injury, learn from it, and come back better from it.

I did two things that should be the first steps in any injury recovery. They go hand-in-hand; to do one, but not the other, risks misdiagnosis and mistreatment:

Get an accurate diagnosis from a professional

Research the hell out of your symptoms

Getting a diagnosis from a good sports doc is ideal but takes the privilege of insurance and access to a good care team. It’s so frustrating when this piece is missing or delayed by weeks (or months!). If you don’t have adequate insurance or a trustworthy doc who’s available, you may be tempted to do only step #2, researching symptoms, and self-diagnose. Or you may go straight to a physical therapist without a full understanding of what’s going on anatomically. Some sports PTs are skilled at diagnosing and can be the trusted med professional you need, but some aren’t. You may be suffering something that needs imaging to confirm it and to show the level of severity (e.g. a metatarsal stress fracture, a hip labrum tear, a hamstring rupture—the list of running-injury horrors goes on) in order to devise the best treatment plan.

So the precursor to the first step above, which you can and should do now if you have the resources and access (sadly, a big if), is assemble a good sports/health team. This post I wrote a year ago shares my long and winding road doing that, which involved self-advocacy to shift from a bad doc to a good one:

Over the past eight days, I experienced what might be called “concierge service” from an incredible med team that regrettably is far from the norm. I was able to correspond directly via email and phone with my orthopedist and his assistant. They’re 4.5 hours away in Vail, so I couldn’t easily go to their office in person, and their tele-med virtual appointments were booked until mid-December. No problem; as their patient, they’d respond to my message without an appointment. They got me an X-ray order ASAP, which our local med center accommodated last Thursday. The X-ray proved inconclusive but was necessary to get a follow-up MRI order.

My doc, from the Steadman Clinic (the best sports-med center in Colorado), called to discuss symptoms and treatment possibilities, and we had an unhurried conversation over the phone. He had all my records in front of him and hadn’t forgotten any of our past discussions. He cared. And he sounded genuinely curious to solve what’s a bit of a mystery and a less usual case (more on that below). He fast-tracked an MRI order to determine conclusively if we’re dealing with a soft-tissue tear and/or the start of stress fracture (he explained why it could be both but hopefully is neither), and he gave me guidance on what to do in the meantime. He also wrote me an order for physical therapy so that I can get an appointment with a recommended PT ASAP.

Our regional hospitals’ imaging departments are booked up for weeks for MRIs. But a patient advocate at the clinic corresponded with my insurance company to get authorization and to notate my order as “expedited.” I was able to schedule the MRI for November 22, so I’ll have a definite diagnosis after that.

I was able to have a fruitful, nuanced conversation with the doc because I also had done step #2, a deep dive of research. This involves questioning conventional wisdom, learning anatomy, and reflecting on your patterns of training, past injuries, and especially your biomechanics.

Understanding the bigger picture of biomechanics

Conventional wisdom says the pain on the side of my knee is the very common running injury known as “IT Band Syndrome,” and treatment involves rest, icing, stretching, and some strengthening exercises. I had done that treatment in the past, and it didn’t fundamentally fix anything. The problem returned when I over-stressed my lower body with a spike in training volume, described later in this post.

I suspected I had something different than typical IT Band Syndrome, and I knew that flawed running form and certain weaknesses were the root problem. I did all I could last week to become an expert on the topic. I realized, thanks largely to having prior sessions with Joe Uhan as a PT and reading his column in iRunFar, that the knee is really “half hip and half ankle,” meaning that “knee problems” are really problems that start above and below the knee.

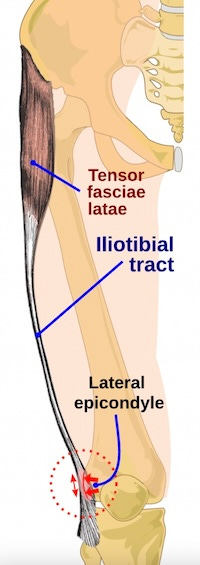

The IT (iliotibial) band is a thick band of fascia running from hip to knee. It gets its “iliotibial” name because it starts at the iliac crest of the pelvis and ends at the tibia (shin bone). Most IT band problems are thought to be caused by excessive friction at the point where it passes over the rounded part of the base of the thigh bone (the lateral epicondyle of the femur) as the knee hinges, as shown in the graphic below. But that isn’t always the case!

My pain is lower down, at the top of the tibia rather than the bottom of the femur, right where the IT band attaches to a bony spot on the tibia called the Gerdy’s tubercle. And the problem, I’m 95 percent sure, is not from the knee hinging (as knees are designed to do). It’s from the femur and tibia rotating and creating side-to-side stress from torsion. This, in turn, makes the bones tug at the spot where the IT band attaches to the tibia, creating stress and pain. The long-term solution, therefore, involves correcting the rotational force so that my knee hinges properly and minimizes the twisting.

The MRI should reveal the degree to which these forces have hurt the IT band, and possibly the bone, at the Gerdy’s tubercle. I may have pushed it to the point of tearing the tendon’s attachment and/or triggering a bone bruise or the first phase of a stress fracture at the head of the tibia. Or, fingers crossed, it just hurts like hell from severe inflammation and microtears of the tissue, which won’t take as long to heal.

You may detect that I’m self-diagnosing, which I am. But this self-diagnosis is made with past input of the knowledgable PT Uhan (who lives out of state, so I can’t see him regularly) and current input of the orthopedist, and I’ll confirm it with the MRI and follow the doctor’s advice. I’ll also get input from the new PT before I commit to long-term treatment.

Meanwhile, I’m doing what non-risky exercises I can that don’t aggravate the pain to begin to address the weak spots that contribute to the problem.

Always a work in progress, never fully fixed

I’m sharing my “case study” to show how studying form and strengthening weak spots or imbalances can help. Whatever your injury, I hope you might learn from this holistic approach and that it might help you.

Few of us have ideal symmetrical form, and it’s very difficult to change your natural running form. But you can do specific strengthening exercises, and be mindful of your flaws and imbalances, to try to run better—especially when fatigue accentuates bad form, as happens during the late stages of a long run or ultra. For me, this means being mindful and trying to minimize over-striding, excessive external rotation of hips and tilting of pelvis, and over-pronation of feet. These three photos illustrate my not-great form.

First, over-striding, shown in the photo below. In my case, it could be worse but also could use improvement. Over-striding means landing with a stiffer and straighter front leg, which creates a braking effect with heel-striking that in turn forces the lower body to absorb a higher level of impact. All of that creates stress on the knee (and contributes to my other knee issue, patella pain). The fix involves improving cadence, engaging the core, and running with a lighter footstrike that lands more directly underneath the hips rather than out in front of the body. (Easier said than done, but improvement is possible with practice.)

Mostly, I need to address excessive external rotation, which I believe is the main cause for the pain at the head of my tibia where the IT band attaches. These two photos (the first from an ultra five years ago, the other from the recent ultra) show how my legs naturally turn out, my feet land with toes pointing out (“duck feet”), my hip rides up and pelvis tilts forward, and my ankles cave in (not pictured here) when I roll forward on my toes.

I’ve been trying with limited success to improve my form, and run with squared hips and parallel feet, for decades. The best I can do is run with more awareness and do exercises to strengthen the areas that help me run with less-turned-out legs and straighter feet.

I’ve redoubled efforts to strengthen glutes (essential for pelvis stability) and strengthen the hip muscles that activate internal rotation. (This video is excellent for an explanation and a couple of exercises, if you’re curious to learn more.) I’m able to do glute, hip, and other core exercises, plus arm strengthening, without causing any discomfort to the knee’s sore area.

If your doctor advises “rest,” it’s likely that “rest” can include beneficial low-impact movement as long as it doesn’t aggravate the injury and you don’t need full bed rest from a traumatic accident or surgery. Maintaining some gentle movement and strength training during injury has mental as well as physical benefits. It makes you feel proactive and more in charge of your recovery, and it strengthens and improves flexibility in areas that would weaken and lose range of motion if you sat around doing nothing.

Return to running gradually, and avoid spikes in volume

I suspect my trouble spot “blew up” with a run-stopping injury because I ran too much at one time, without adequate training beforehand, and without adequate recovery after those hard efforts.

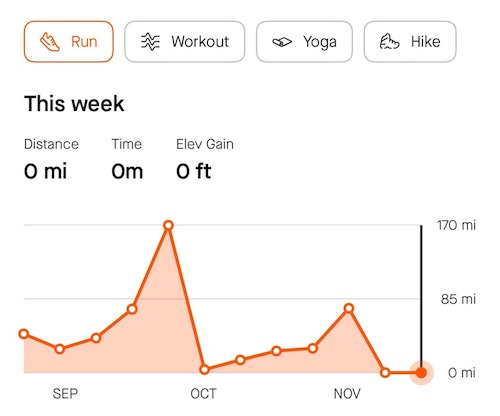

I did not follow my own advice, articulated in this post “Signs of Aging as a Runner,” to train consistently and avoid dramatic swings or spikes in training volume (mileage/duration) and load (stress/strain). Check out the two spikes in my running volume the past couple of months. This illustrates what you should not do if you want to stay injury-free, especially if you’re past age 50 like me.

My body cooperated and managed when I pushed it to go 170 miles in a week during late September’s Grand to Grand Ultra, and then I gave it a rest with zero-to-moderate volume for four weeks afterward. But when I pushed it five weeks later in early November to go 100 miles in one 24-hour session—because my ego wanted a sub-24-hour 100-miler in 2024, and I thought I was invincible—it said, “Nope, I’m done,” and broke down with pain after 50 miles. (Sigh—live and relearn.)

I vow to return to running gradually, with a slow buildup, and maintain consistency following this injury. If that means scratching my plan to run a road marathon on the first weekend of March, so be it.

I’m also bracing myself for the post-injury return to running to feel unsatisfying, even frustrating. It’s best to think of the first phase of running post-injury as an extension of physical therapy, rather than “real” running that makes you sweaty and happy.

The first runs back should be extremely short and interspersed with walking breaks; for example, three minutes running, three minutes walking, three times, for only 18 minutes total. The point of these comeback sessions is to re-engage and re-educate the muscles and joints involved with running, not to get a high-intensity workout. Carefully and gradually increase the length of the running intervals only if you’re running pain free. Also, during this comeback phase, run on a flat, soft, even surface like a track or smooth dirt path; avoid hills and technical terrain.

As you recover, try to focus on all-over “wellness” instead of run-specific “training.” That means improving sleep, nutrition, and aspects of fitness that you can work on while injured, such as strength and mobility.

I’m feeling motivated and mildly relieved rather than sorry for myself, surprisingly, because it could be so much worse. The full-stop nature of the injury forces a reset, re-evaluation, and recommitment to train smart, which I needed. I’m grateful I was able to run as much as I did this past year and met my big goal in late September. I’m also deeply grateful I have a caring top-notch trio of sports rehab experts—ortho, PT, massage therapist.

Humbled, I’m open to learning from this setback and using the time off for other healthy pursuits, like reading and yoga. I’ve always said that injuries are great teachers. Sometimes we forget or fail and need to repeat the lesson.

For more on lateral knee pain involving the IT band, I recommend these two articles:

Ultra PT: The Dreaded IT Band Syndrome (a smart short overview from UltraRunning magazine)

Joe’s Fix-It Series: IT Band Pain (a longer and more comprehensive article from iRunFar.com)

Thank you

Yesterday, I reached a goal of 3,000 subscribers, which I had hoped to hit by year’s end. Thank you so much for reading this newsletter (especially given the thousands of other Substacks and media vying for your attention) and for sharing it.

Got an injury-coping tip that I didn’t cover? Please share in the comments below!

Sarah, thank you for sharing your journey through recovery and the mental reset that injury demands. Your approach to ‘project-managing’ recovery is such a helpful framework—it’s empowering to think of healing as an active process rather than a passive waiting game. Your insights on biomechanics and how seemingly small issues, like rotational force, can create such impact is eye-opening, too.

A few other coping tips I’ve found helpful during injury recovery include:

- Establish small, achievable goals (like working on upper body strength or flexibility) to keep a sense of progress and avoid frustration during recovery.

- Visualize the specific muscles or areas healing and returning to full strength, which can help with focus and maintaining a positive outlook.

- While rest is essential, gentle activities like water walking or light resistance bands (as tolerated) can promote circulation and maintain muscle tone around the injured area.

- Injuries can take a mental toll, so practices like mindfulness or meditation can support mental resilience while the body heals.

Cheers to embracing setbacks as teachers and to a healthy, gradual return to the trails. Here’s hoping your story inspires all of us to listen more closely to our bodies!

So sorry to hear you’re struggling with injury. I am also on my own journey with an IT band issue, and I actually just published an article on here yesterday about strategies for dealing with injury that I’ve found helpful over the past few months.

If you haven’t already, perhaps try looking into PRP (platelet rich plasma) injections that seem to have some promising benefits when done in conjunction with physical therapy. I just had one and I’m cautiously optimistic 🤞