Welcome new subscribers, and thanks for being here. Several of you discovered my newsletter on Sunday after

linked to it in her post. If you’re new here, I hope you might make time for this anniversary post, which describes why I write and links to five posts that represent this newsletter’s subjects and style. If this week’s topic doesn’t hold your interest, scroll down toward the end for some reading recommendations.I keep returning to the theme of aging not only because it’s universal, but because I feel and measure it acutely as a runner in my mid-fifties. And no one, it seems, can tell me with much clarity what to expect in terms of age-related decline and how best to manage it.

The roadmap for aging as a female runner is almost indecipherable and mostly anecdotal, reminding me of the maps my mother used to draw when I was a young driver. To help me get somewhere, she’d grab a pen and the steno pad on which she wrote grocery lists and start drawing a route while narrating like this: “You drive a ways down the 101 past the mall, and then when you see a sign for Rice—think weddings!—get off and go toward the ocean.” Then she’d hand me her piece of paper with an unlabeled squiggle of a line, as if that’s all the guidance I needed.

The other day, however, I discovered some age-related advice in UltraRunning magazine that is somewhat helpful, which I’ll share below with my take on it. First, some context.

I developed as a runner from my mid-twenties through thirties while repeatedly reading that age 40 triggered the “masters” category, which implied “older and slower.”

I hit my 5K PR (18:45) at 34, after having two babies, and marathon PR (3:05:53) at 39. Female runners I followed and admired—such as marathoners Uta Pippig and Paula Radcliffe, or ultrarunners Ann Trason and Kami Semick—faded after their early forties. Media coverage always focused on younger up-and-comers, so trying to improve after 40 felt somewhat subversive and far-fetched, but exciting.

In my forties, I transitioned more fully to ultra-distance trail racing, which felt empowering because experience and strategy determined success almost as much as physiological attributes like oxygen-carrying-capacity, body mass, and strength. Steadiness, endurance, and mental tenacity mattered more than raw speed at ultras. I could still improve as an ultrarunner, even if my V02 max declined and I gained some weight, as long as I ran smart and stayed strong and uninjured. I kept improving through my mid-forties, but then those performance gains tapered off and became harder to realize.

Facing 50, in 2019, my road marathon time measured a still-satisfying 3:42. I still finished ultras in the top quarter or third of the overall field. And that September, as a 50th birthday present to myself, I returned to the race that means so much to me—the seven-day, self-supported 170-mile Grand to Grand Ultra stage race—and I won it.

But five years later, post-menopause, my athletic decline has accelerated and, last weekend, became literally dizzying.

Doing the Grand to Grand Ultra last month (recap here) provided a measuring stick for how much I’ve slowed down in five years. Granted, the course conditions were a bit more difficult, according to my memory and others (deeper, softer sand and more dense vegetation in cross-country sections), and my pack was a bit heavier because I carried more food and a thicker sleeping bag. But this year’s Grand to Grand took me substantially longer—about 4.5 hours longer. Nearly an hour of that can be attributed to getting lost at one point. Overall, however, I ran a slower pace each stage.

My speed is hampered by a shuffle-shuffle stride that agility drills this past year—aimed at promoting quick-footedness and cadence—have not improved. And that declining agility caused a scary setback last weekend.

On Saturday, I ran up Bridal Veil Road above Telluride to enjoy the rocky old mining road one more time before snow fully covers it. I was feeling good, running with more power post-Grand to Grand Ultra recovery. But I was being spacey and defaulting to the shuffle-shuffle, so I caught a toe. Bam, I went down with a hard thud on my hands.

I didn’t hit any other part of my body, so I felt relatively OK, but I took a moment to rest on the ground before standing. Damn, I thought, that felt like a slow-mo body blow. I started running again, but more cautiously and with more hiking breaks mixed in, and thought, no big deal.

Turns out, it kind of was a big deal. That night, rolling over in bed while sleeping, a sickening vertigo sensation awakened me. It felt like being rolled horizontally in a barrel. I cried out in fear and woke up my husband. The nauseating rolling sensation happened a second time. So I turned on my light, found the reading glasses on which I now rely, and did some research. Dr. Google told me I probably had benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), an inner-ear disorder cause by fine hairlike sensors getting knocked loose. I blamed it on my fall.

The next day, I self-administered something called the Epley maneuver, which can resolve BPPV, and it seemed to help. I slept better Sunday night but still felt “off” and a bit woozy in the morning, as if I were jet lagged and hungover. (I’ve had zero alcohol—I don’t drink at home anymore—and no medication that would affect stability.)

I nonetheless embarked on a gentle, steady run on a smooth dirt road, which felt good and normal, so I figured I was all better. But the next morning, I felt unsteady and lurched to the side again when I got out of bed.

More consulting with Google led me to conclude I probably gave myself a mild concussion with that fall. I didn’t hit my head against anything, but the jolt might have whiplashed my brain in my skull. I haven’t seen a doctor because there’s nothing to do except take it easy and be careful until I feel normal again, and my symptoms aren’t too bad. I can read and drive fine.

I’m sharing these details because the whole thing left me rattled about running and feeling my age—feeling vulnerable and weaker, that is. It’s like overnight, I went from bold to old, from fast to fragile.

At the start of summer, I wrote in this post about how I’m more risk averse and fearful of mountain conditions such as electrical storms and large-animal encounters. Now I’m nervous about falling, too, and feeling as if this timidity could accelerate an exit from the sport.

But I want to keep running long distances in the mountains. I want to be badass and to age with guts more than grace. I want to participate in ultras even if it means I may chase cutoff times. I want to prove I can finish the Hardrock Hundred, if I can ever gain a damn entry spot.

Feeling discouraged and wondering about my shelf life as a runner (when is it time to settle with hiking and stop trying to run these trails?), I read with more than a usual amount of curiosity two articles in UltraRunning magazine about ultrarunning after 50 and longevity in the sport, written by coach Jason Koop and sports scientist Nick Tiller. I admire them both as writers and researchers—but they’re both men, and still in their forties, so their understanding of the aging female athlete is inherently limited.

Their articles are in this issue but require a subscription to read. (Go ahead and subscribe to this classic magazine! It’s still the voice of the sport.) I’ll summarize some of their points.

The menopause “wild card”

Notably, neither expert addresses menopause, although Tiller states the obvious in passing: “Menopause is a wild card. Typically occurring between 45 and 55, it brings with it new challenges in an already challenging sport: changes in hormonal status, substrate efficiency and injury risk, all affecting the average age of peak performance in females.” No shit, Sherlock (and in the future, please avoid jargon such “substrate efficiency”). What does this hormonal nosedive mean for performance, and for loss of muscle mass and bone density, and what’s the best way to manage it?

I’m already experimenting with hormone replacement and would like more specific guidance, such as, if I upped my estrogen dosage, rather than taking the minimum, would I realize benefits to my joint and bone health and maybe, just maybe, run faster? If my blood test reveals that my testosterone level is nonexistent now, is it advisable to take testosterone off label from a compounding pharmacy (since the FDA has not approved testosterone therapy for women), and if so, how much is OK so that I don’t trigger “doping” or unhealthy weight loss or other side effects?

Has anyone even asked and studied at which point legit menopausal hormone therapy crosses over to inappropriate and risky performance enhancement, or are we old ladies not taken seriously enough as competitors to be deemed worthy of such sports-science research?

I have many questions and haven’t found sports scientists who have evidence-based guidance.

Rant over, let me share some of their interesting non-gender-specific insights.

What we can and should do as aging endurance athletes

I appreciated and related to this solid advice from their articles:

Reduce risk of musculoskeletal injury; prioritize protecting the fitness you have. This means training more consistently, without dramatic swings in the training volume or load, and maintaining the fitness you’ve got. Therefore, I won’t take a full break from training this winter (as I usually did in years past, between Thanksgiving and Christmas), because it’s important to stay in “maintenance mode” to keep a base level of running fitness. It also means doing strength training and mobility exercises to build the body’s resiliency and help prevent injury. Women, we gotta lift heavy to prevent muscle loss and keep our bones strong!

That said, it’s also important to build in more recovery after hard workouts. Looking ahead at my plan to train for a spring marathon, for example, I figure I’ll do speed work and a depleting long run every other week, rather than every week, and have a “plain vanilla” training week in between, as a way to adequately recover and adapt to those hard workouts. Speaking of speed work, Tiller has a valuable tip: do some intervals uphill, at a gradient of 4 to 12 percent, instead of always on flat; “it’ll evoke the necessary oxygen uptake without the same impact stress.” (I would add: After each interval, walk or gently jog back down the hill, don’t hammer.) I also may reduce my running to four times a week, rather than the typical five or six, to have adequate time for the strength and mobility training mentioned above.

Recognize and accept that life stressors (such as getting jet-lagged or sick) and training stress (such as strength training or high-intensity intervals) hit harder when we’re older. “Respect that the recovery and adaptation processes are less malleable than they were a couple of decades earlier,” writes Koop.

Stop fighting your physiology; pick your battles. I like what Tiller has to say on this, so I’ll quote it in its entirety: “There’s a natural, age-related decline in fitness. It’s driven mainly by oxygen uptake, which falls by 1 - 2 percent every year after age 30. This is initially due to diminished cardiovascular capacity and later by peripheral factors like the ability of the muscles to fully utilize the oxygen they receive. You have a choice to make in the face of this inevitable truth [emphasis added]. Your first option is to train harder, spend more time doing intervals, and fight tooth and nail to retain your top-end fitness. This may work for a while, but it’s an exercise in diminishing returns—becoming more difficult with each passing year and requiring a lot of effort with little payoff. It may also increase your injury risk. The alternative is to redirect your efforts to training those aspects over which you have greater control and which may confer greater performance benefits. As mentioned, maximal oxygen uptake isn’t as important for long ultras as we used to think, whereas running economy, lactate threshold and peripheral conditioning can all be better maintained or even improved well into older age. So, pick your battles.”

I’ll add a tip to those from Koop and Tiller. Throughout life, and I believe even more as we age, social connections are vital and tied to well-being. As runners, I’ve found it’s helpful to run occasionally with younger speedsters for the challenge, motivation, and connection to the next generation. But it’s even more helpful to have older mentors. I’m fortunate to have a handful of badass ultrarunning mentors in their sixties and seventies who show me the way and inspire me to persevere (Sophie, Suzanna, Becky, Rick, Scotty, John, I’m looking at all of you). And I intend to be that mentor and role model for women younger than I. So make an effort to nurture relationships with runner buddies.

Recommended reading

Briefly, I’d like to share a couple of books, and a couple of Substack posts, I really enjoyed and/or that broadened my thinking.

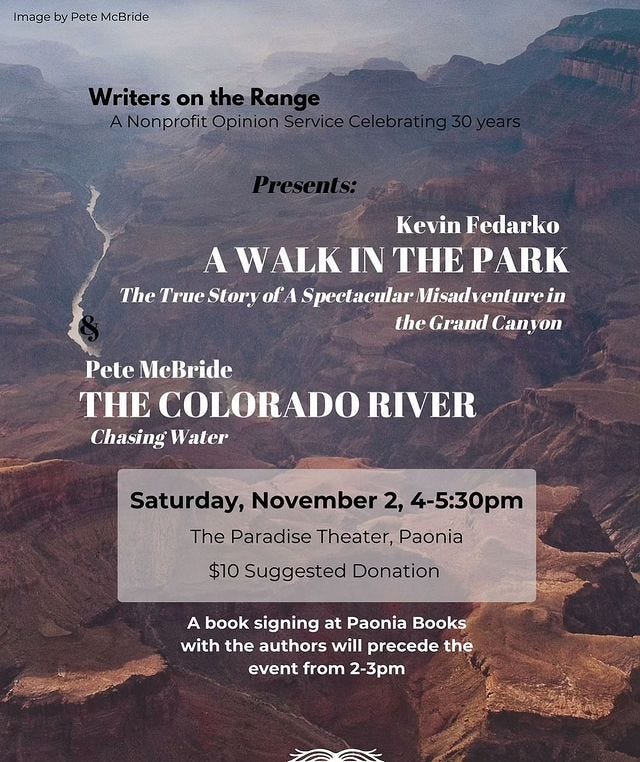

Last week, I finished the best nonfiction book I’ve read this year: “A Walk in the Park” by Kevin Fedarko. At 500 pages, it’s thick but readable. Fedarko (whose first book, “The Emerald Mile,” about Grand Canyon river-running and dam-building is a must-read too) embarks on a 750ish-mile trek the length of the Grand Canyon, where trails are few and far between and survival depends on finding hidden puddles of water. He and his buddy, the photographer Pete McBride, begin their journey in a Bill Bryson-esque bumbling way and, thoroughly humbled, toughen up and do their homework for a second attempt. Like the many tributaries that carve deep side canyons, Fedarko’s narrative detours from their trek to delve into history, geology, and—perhaps most importantly and interestingly—the stories of the indigenous tribes. Even if you’re not on a Grand Canyon kick like me (I was there in September and am returning this weekend), I think anyone who has an interest in trekking, adventure, natural history, and environmental politics will find this book engaging and enlightening.

Bonus: Fedarko is speaking Saturday, November 2, in Paonia. A year ago, I wrote this post about why Paonia is a special getaway, with things to do and trails to run there. This is a great opportunity to hear this author and explore the North Fork Valley!

My favorite recent fiction read: “The Wedding People” by Alison Espach. I laughed out loud and didn’t want it to end. The setup is a great hook: a suicidal English professor checks into a special inn at a getaway destination intending to end her life but finds herself surrounded by an annoying wedding party, and then she forms an unexpected connection with the bride and groom. I won’t say more except that I loved spending time with these characters. It’s so fun to discover a fun book!

Two recent Substack posts that struck a chord with me:

“The Death of the Pragmatic Western Republican” by

made me better understand—and grieve—the decline of the moderate, pragmatic middle. My dad and father-in-law used to be moderate Republicans. We need more of them. This post’s examples are quite eye-opening.And, I very much relate to this post by

, about a “bad habit”—heavy drinking—that affected her writing. I could substitute “Running” for “Writing” in her headline and write a similar post. I also have a happier ending (new beginning?), thankfully.And that’s all for this week. I’m finishing this while sitting in a metal folding chair in the San Miguel County Courthouse, called for jury selection for a one-day trial, my laptop getting WiFi off my phone (which is supposed to be off), and the bailiff is giving me the evil eye for multitasking. If this post has more than the usual number of typos due to inadequate proofreading, that’s why.

If you would like to support my writing, but would rather not commit to a paid subscription, please consider leaving a tip in my “buy me a coffee” virtual tip jar.

The lack of research about menopause is infuriating. Just the most blatant case of gender discrimination in medicine I can think of. I don’t know anything about ultra running and menopause but virtually everything I have read for the go (general population) says that weight training and increased protein intake is essential for keeping muscle mass.

This hits hard! I started running at age 14 when we knew nothing about training. I hammered every run, there was no such thing as easy. At 43ish I had to decide if I wanted to keep chasing Boston or be able to walk at 80, and this was hard for someone whose whole identity was as a runner. I still run, and the pace is laughably slow, but I long distance hike more and love it. I think it's all about having multiple identities...at least, that's what worked for me.