Change Your Thinking to Run Better

How I'm practicing mental strategies for ultras, plus a special book review

My preparation for July’s Hardrock Hundred needs as much mental as physical training, and a six-hour effort last Saturday provided a great albeit challenging opportunity to train my brain as much as my legs.

I anticipate that Hardrock will take me 40+ hours given the extreme conditions of ascending some 33,000 feet, and descending an equal amount, over nine major mountain passes on extra-rugged singletrack in thin air. (The event has a 48-hour limit.) That averages to a pedestrian hiking pace of slightly slower than three miles per hour. How and why would I and other so-called runners go so slowly? Partly, it’s the extra time needed at aid stations to eat, change clothing layers, and rest in advance of the towering mountain passes still to come. But mostly, it’s because so much of the terrain is un-runnable. When I hit the near-vertical scree headwall of Grant Swamp Pass, around mile 87, I’ll use my hands to literally crawl up it, and one mile there may take about an hour.

On top of that, I am much slower than most of the other runners who’ll be there, largely because of subpar downhill skills. I can pass others on the uphills thanks to strength and efficiency while fast-hiking, but they invariably pass me back on the downhills because I descend timidly and cautiously, my lower body protesting with simmering pain from impact and tension from fear of falling.

Mentally, therefore, I need to cultivate and practice some key attitudes, including: patience, positivity, acceptance, and self-compassion. I also need to practice setting aside—or dispassionately moving through and letting go of—thoughts and feelings involving envy, comparison, frustration, and self-pity. This mindset shift is much easier said than done, and even if I know objectively what and how to think for better performance, I struggle to do it. I still get pissed off and engage in self-pity-parties.

But, practice helps, and in Moab Saturday, I had ample opportunity to practice my mental game—specifically, replacing knee-jerk automatic thoughts with more helpful positive thoughts. Thinking better leads to feeling and acting better. It’s homegrown cognitive-behavioral therapy on the fly.

The setting, as previewed in last week’s post, was a repeat-lap timed event, and I entered the six-hour division. It was part of the Running Up for Air series (RUFA) that raises money and awareness for environmental causes.

I wrote about my negative thought pattern during another RUFA event a year ago, which shows my mental training needs ongoing work: “Compared to the others who kept cranking out the laps and running past me with greater skill on the downhill, I felt frustratingly average. … Discouragement settled over me like the polluted inversion layer.” I entered the Moab event determined to accept my average-ness and combat discouragement with enthusiasm and gratitude.

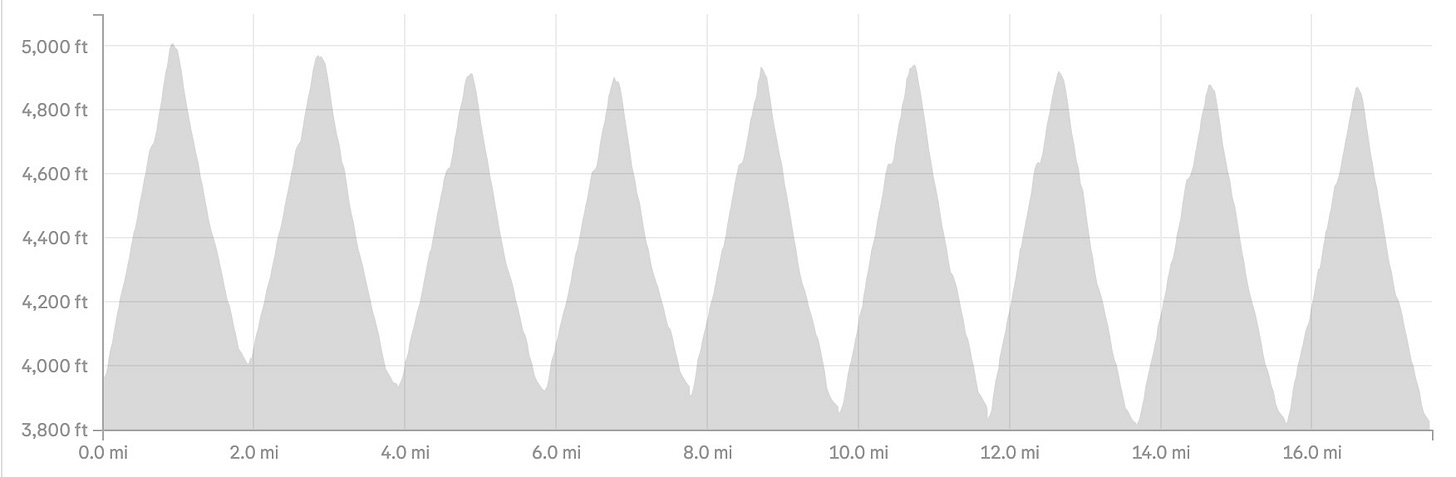

The route, on the west side of town overlooking the Colorado River, climbs sharply up the aptly-named Stairmaster Trail for just under one mile, gaining nearly 900 feet. The uphill track features big rocks to step up and some zig-zaggy switchbacks. The return descent follows a parallel “trail”—more like a rock cascade—of steep, uneven slickrock.

I entered with some clear goals: (1) don’t fall and re-injure myself; (2) aim for 10 laps, but regardless of getting to 10, stay in the event for the six-hour duration unless my injury spot acts up; and (3) practice mental strategies along with intentional fueling and hydration that I’ll need for Hardrock success.

We started at 8 a.m. in a cluster and moved quickly due to the near-freezing temperatures. On fresh legs with people on my tail, I hustled up the first lap as quickly as I could, my heart rate manageable (because this route stood at significantly lower elevation than where I live) but my legs already feeling worked. I settled into the mid pack. Then on the downhill portion, other runners flowed past me like water on the slickrock cascade while I shuffle-jogged, aiming for a light foot strike and quick turnover but also restrained with caution.

Only one lap in, I felt the twinges of comparison, envy, and self-criticism combining into discouragement, but I fought back with self-compassion.

It was only 10 weeks ago, after all, that I eased back to running after three months of recovery following a partially torn iliotibial (IT) band (where it attaches to the tibia head). In mid-February, not too long ago, my physical therapist demonstrated itty-bitty step-downs from only the height of a yoga block, warning me to reintroduce eccentric movement—the lengthening and activation of the quad muscle and IT band on a downward stride—very gradually and carefully. And here I was, less than two months later, asking my body to repeatedly run a mile down an uneven precipitous slope on hard-as-concrete rock. I shifted my attitude to inward-cheerleader and congratulated myself on being able to do this at all.

The first lap took 35 minutes, about 20 on ascent and 15 on descent. Subsequent laps would take 40 to 45 minutes due to bathroom breaks, eating and hydration refills, and general fatigue. Side note: It blows my mind that second-place finisher in the 12-hour division, Sarah Ostaszewski, did her final lap—getting to 21 laps (!)—in just 29 minutes, hustling to finish the final lap before the cutoff.

Fast forward to about three hours in, and I could do the math to realize my goal of 10 laps was out of reach in the six-hour limit, and I’d have to work hard to fit in nine. Again, discouragement and comparison crept back into my head—because other women were lapping me and on their way to getting 10 or 11 laps done in the six hours— but I tried with some success to turn my feelings around to inspiration.

Repeatedly, I focused with amazement on 60-year-old Anita Ortiz, the 2009 Western States 100 champ, who kept blowing by me and others, and she was in the 12-hour division, ostensibly pacing herself to do twice the effort as us in the six-hour. I have been in other ultras with her, and she’s always way, way ahead. And she’s five years older than I.

She’s light years out of your league, so accept it and admire her, I told myself. I mused that she too probably struggles with aging and being slower than she used to be, even though she seems so fast to me. Turns out, she does, as revealed in this well-written UltraRunning profile from four years ago when she was 56.

Anita had an amazing day, winning the 12-hour division overall with 21 laps, even ahead of Sarah Ostaszewski, age 33, who has formidable ultra cred including wins at Cocodona 250, Moab 240, and the course record at the Ouray 100.

There were so many amazing women out there! I felt lucky to be amongst them, grateful I had shown up. Women like Darcy Piceu, 10-time Hardrock finisher and three-time winner of it (plus multi-winner of other 100s such as Wasatch). Maggie Guterl, past Cocodona 250 winner and Bigs Backyard last person standing. And Meghan Hicks, editor in chief of iRunFar and past Marathon des Sables champ. Plus, several amazing moms were doing the event with their kids, like Mindy Campbell, whose husband Jared created the RUFA series, and another woman doing laps with a big baby strapped to her chest in a front carrier.

By the eighth lap, my legs had turned Gumby-like, threatening to buckle and spasm out of control. Almost everything on my lower body hurt—my lower back, my hamstrings, my “good” knee’s patella, my screaming feet—except, oddly and wonderfully, my injury spot (where the IT band attaches at the tibia head). It kept quiet and behaved. So I kept going, looking at my watch and stressing out about finishing the ninth lap before the six-hour limit.

On the final lap, I knew I had shredded my quads’ muscles, peppering them with micro-tears that would blow up with inflammation afterward, due to the overload of stress from going up some 9000 feet and descending the same. I hadn’t done this much vert in one go since the prior summer. I would pay for it with debilitating soreness in the three days following. (But Hardrock features about 3.5 times as much vert, so I gotta adapt!)

When I finished with 10 minutes to spare, I saw that I had gone about 17.5 miles—an average pace of 19:53, or about three miles per hour. “Welp, that’s good practice for making peace with a Hardrock pace,” I said at the end. Actually, a slightly-sub-20-minute average pace would be quite respectable at Hardrock.

Buzz, the co-race director, told all of us “legends” (his word) to gather for a photo. I looked to my sides, suddenly embarrassed and feeling out of place, the Sesame Street lyrics “One of these things is not like the other, one of these things doesn’t belong” playing in my head.

Then my practiced mental strategizing came to the rescue, squashing the negative automatic thought with a more positive way of viewing the situation, and I thought, fuck it, I do belong! I showed up. I’ve been at this game as long or longer as these other ladies. Sure they’re all faster, but so what? I figured out last year, during an epiphany at the Grand to Grand Ultra, that I no longer need to prove myself or care so much what others think of me or how I measure up to them. I can do my own thing, at my own pace, and take joy in being a part of the sport for as long as I can.

So I got in the line with these women I admire and felt genuinely happy about my day out there. To think: I did 9000ish feet of vert after struggling to go up and down stairs pain-free just three months ago!

It was a great six-hour practice, mentally as much as physically, for my big goal of Hardrock (and leading up to it, the May 10 Quad Rock 50). My stoke his high.

Related reading:

Last week’s Q&A with adventurer Buzz Burrell, the Moab RUFA co-director

My race report from the RUFA Grandeur Peak-Salt Lake City event

Latest book rec

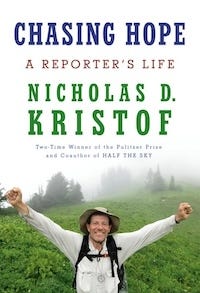

I read plenty of fun fiction, most recently We All Live Here by JoJo Moyes. But to keep my brain sharp and endeavor to be a lifelong learner, I mix in some weightier nonfiction with rom-com and thriller chick lit. I can’t overstate how much I appreciated and felt moved by the memoir I just finished by New York Times foreign correspondent-turned-columnist Nicholas Kristof, called Chasing Hope: A Reporter’s Life (buy it here). This is the five-star review I gave it on Goodreads:

The world would be a better place if more people read this book.

On one level, it's a history lesson of recent world events that we should all learn more about and remember—events that show the worst of humanity, usually sparked by repressive autocrats (for example, the massacre of protestors around Beijing after the pro-democracy uprising, and genocide in Sudan and in Myanmar against the Rohingya, a people about whom I was totally ignorant) and also the best and bravest of humanity (profiles of the aid workers in these areas, and many leaders' and activists' dedication to work for freedom and human rights).

On another level, it's a compelling memoir about an extraordinary upbringing of a boy born to two intellectuals and activists who raised him in the most middle-class American way, and his roots to his family’s patch of Oregon farmland ground his global reporting with humility and an understanding of poverty and addiction that many urban and academic progressives fail to grasp. I also loved the inside look at how The New York Times has evolved over the past 40 or so years.

Ultimately, it becomes a trenchant critique of our political system—both the left and the right—and all the red flags that preceded a second Trump term, with a warning about the rapid shift in norms that we're witnessing now because of the demagogue in the White House. In one of his last pages, Kristof write:

"I've seen how countries can drift toward authoritarianism, using populist measures. ... None of this would turn the United States into North Korea, but democracy is a sliding scale, and we could end up less like Canada and more like Hungary. We could even end up with fissures so severe ... that they would lead to serious efforts at secession. What I've seen repeatedly in my career is that history evolves slowly for a time and then lurches. Lenin is said to have observed (it's a dubious attribution): ‘There are decades when nothing happens, and there are weeks when decades happen.’ So much is at stake, and that's one reason journalists must not settle for being stenographers, quoting first one side and then the other. Our foremost obligation is to report the truth, wherever it lies and whomever it offends. This is tricky to navigate in practice, but today once again—as in McCarthyism, the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War—truth must be paramount. We journalists shouldn't dispassionately observe our way into authoritarianism; we shouldn't be neutral about holding up democracy."

Chasing Hope is highly readable and never too heavy in spite of the deadly serious topics. Mostly, it left me inspired with resolute hope and feeling that the best journalists are true heroes whom we need more than ever.

I’d love to hear in the comments below any mental strategies you leverage at ultras and/or any book recommendations.

Thank you for taking the time to share your inner dialog. Always interesting - we all do it to some degree - even while others are probably looking at you thinking, "She makes it look so easy!" (I thought you did look good, especially so soon after 3 months off - I'm guessing the strength training really mattered).

My friend Peter Bakwin - still the only person to do Double Hardrock - remains quite fit but never races. Why? Because external expectations would intrude into his internal equanimity, which he'd rather not happen.

HR100 is a colossal route, yet only a few parts are technical with much cruising, while RUFA Moab keeps one's attention every step. Good practice and a great day - thank you!

btw, I am Co-Race Director with 4 good friends, including Melissa.

"Compare and Despair"

Fun piece but I'm a tad surprised at all the angst re other's abilities. I'm 67 and at the climbing gym most are able to do harder routes and it really doesn't bother me as I enjoy the act and sensations of climbing. As long as I'm doing my best atm, the result is not critical. Indeed, revel in the healing of your IT band issue