It was so cold last Saturday that I decided to postpone my traditional New Year’s Day long run until temps warmed up to the teens the following day. On January 2, I drove 45 minutes to Ridgway to run 21 miles, and in the process, to reflect on the past and dream about the year ahead.

The cloudless blue sky looked saturated in color above the snow-covered landscape. Running along rural County Roads 10 and 12, I gazed at fenced-in pastures dotted with cows and farm homes, scrub oak covering hillsides that rise to a plateau on the Cimarron Range, and grander peaks forming the backdrop to Ouray. It was nice to see acreage in this corner of the county seemed relatively unchanged from the passage of decades.

Like much of Colorado, Ridgway has been in transition, from a railroad hub populated by homesteaders in the late 19th century, to an insular ranching community half a century ago, to a more densely populated bedroom community with luxury homes on its outskirts. (For Colorado history, I highly recommend a book by local rancher Pete Decker, Old Fences, New Neighbors, that captures the economic and lifestyle transition of Ridgway and Ouray County from the 1960s to early 2000s.)

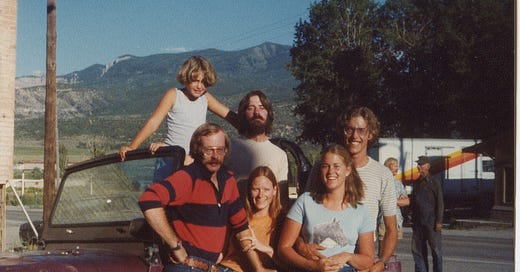

Ridgway’s historic main street area with its Old West storefronts holds a formative yet fuzzy place in my wild-child memories, because as a 9-year-old in the summer of 1978, and again in ’79, I spent time there with four older siblings who supervised me as much or more than my parents did.

My eldest brother, then 24, and father had the enterprising (a.k.a. nutty) idea to buy the town’s cowboy cafe, The Little Chef, so my brother could manage it. It was the kind of place that served chicken fried steaks and had a large jar of pickled hardboiled eggs on the carved wooden bar. My middle brother, 19, worked as a waiter and dishwasher, and I remember him telling a table full of customers that they were out of tuna salad, out of egg salad, and out of several other menu items after an inspector came by and made them clean out the fridge.

While hanging outside my brother’s rental near the restaurant, I amused myself by building forts, wading in an irrigation ditch, and reading paperbacks published by Dell Yearling Books. Like Harriet the Spy, I casually observed my older sibs and their friends roll and smoke joints, and when they weren’t looking, I’d steal what they called the “roach” so that I could collect my own “stash.” I laugh out loud now at the memory of all those stubs of stinky joints. I hid them in a white cardboard jewelry box, and then, in a panic at the end of summer, I buried it in the dirt to hide my crime.

We also rode inner tubes down the Uncompahgre River from Ridgway toward Montrose, one of the tires blown up around a cooler to have beers and sodas at hand during the float. After getting out of the river, they urged me, the youngest, to scramble up to Highway 550 and put my thumb out to hitch a ride back to town, because then surely a car would pull over, at which point the rest of them would run up and get in the vehicle. I’m pretty sure this never happened, but they mentioned it as a funny dare enough times that an image of me, with my Dorothy Hamill haircut and thumb out, an inner tube hanging off my arm, took hold in my mind.

The Little Chef didn’t make it, and my eldest siblings struggled with personal and financial problems, but I think I benefitted from those wacky chapters in our upbringing. Being a kid tagging along in Ridgway and Telluride with older siblings in the ’70s—and feeling their love and inclusion—made me grow up quickly and become resourceful and adventurous.

While running along, I thought about how much our childhood experiences and family roots shape us into the adults we become, and how the past is always present to draw on for character, or to try (unsuccessfully) to escape.

A lonely-looking mare in a snow-filled pasture watched me as I ran closer, and she seemed to beckon, so I stopped to give her attention, rubbing behind her ears and softly blowing in her nose—this connection with horses also a consequence of childhood.

I often tell the clients I coach to “be in the mile you’re in,” highly observant of the surroundings, and I practice that mindfulness, too, especially to get through a rough patch in an ultra. But isn’t letting your mind wander to ruminate and imagine, instead of only focusing on the present, part of the value of a run?

I felt the tug of auld lang syne, missing my harebrained parents and cool older siblings, and missing my identity as the youngster. Like this town, we have aged and transitioned so much.

Then I focused on the scene straight ahead, the road leading to the trailhead for Courthouse Mountain—a majestic, blocky-looking summit. My husband and I have talked for the past couple of summers of exploring that mountain, and yet we haven’t made it happen. I’ll add it to my list of to-do trails this summer.

I think I know this region, and yet innumerable county roads and trails remain unfamiliar to me. I’m going to make more of an effort to branch out and explore.

I’ve been working my way through Addie Bracy’s new book, Mental Training for Ultrarunning, and using her worksheets to drill down to the “why” of my training and racing. I realize how my motivators have changed since I started running marathons in 1995 and ultras in 2007. I still use races to challenge myself to run my best on a given day—and to celebrate the training leading up to the race—but aiming for PRs, age-group wins and the occasional podium spot has faded in importance. Now, my training and racing are driven mainly by wanting to stay healthy and to slow down aging, to explore and experience the outdoors, and to have the structure of training and goals. I also do it to experience the fun and escapism of a day trip to an ultra event, and to have quiet days like this one in Ridgway that provide unplugged “me time” to think.

I’m spooked by older people whom I care about suffering serious health problems and losing their mobility. Thirty years from now, I want to be like this man who wrote in an Outside article, “Why I Still Love Racing at 82,” about how he keeps racing and setting new time goals for himself.

In 2021, I ran 2137 miles, which may sound impressive but is significantly less than many ultrarunners. For each of the past four years, I’ve run around 2100 miles total, down from a peak of over 2600 in 2017. When thinking about new-year goals, I thought perhaps I should try to get the annual mileage total back to 2500. Then I thought, no, the goal is to stay consistent and to keep at it. Consistency and longevity are underrated in this sport.

I’ve mostly figured out my 2022 racing plans, and I’m excited about training for them. These events give me optimism, structure, and a social date on the calendar; plus, a reason to do the kind of daydreamy, depleting and gratifying long runs like the one looping around Ridgway.

Ventura Marathon in Ojai, California, February 27

Behind the Rocks 50K in Moab, Utah, March 26

Desert Rats 50K in Fruita, April 16

Miwok 100K in the Marin Headlands of the Bay Area, May 7

If I get in through this month’s lottery, High Lonesome 100, in the Collegiate Peaks west of Buena Vista, July 22

If I don’t get into High Lonesome, then backup 100 is Run Rabbit Run in Steamboat Springs, September 16

Hanging Flume 50K near Naturita, in October date TBD

What races or goals are you most excited about for 2022?

Thank you for reading my weekly posts, which sometimes go down the rabbit hole of memoir. Please subscribe for weekly updates, and consider a paid subscription for bonus content and an invitation to a monthly online meetup. Our next Zoom date is January 23.

Related posts:

My days of ultras may be over. That remains to be seen. But over the moon fired up about the 5K and 10K road races at the Senior Olympics in May.

When I worked at the True Grit in '91 all the old timers would head to the Little Chef (just a bar then, I think) to keep drinking after we booted them out. There was a rumor that these local ranchers would cut off and pin hippies' ponytails to the wall of the Chef. I miss those days.