I’m generally an optimist who looks for lessons in setbacks and silver linings in bad news. I tell myself things could always be worse. I know that disappointing times make the good times feel better.

But last week, in spite of thoroughly enjoying time with my daughter and seeing Wicked in a special theater, and in spite of knowing that things could be much worse, I felt unusually down and pessimistic. I felt utterly out of sorts—as if I inhabited someone else’s body and brain—and began to doubt I’d get better. I’m not gonna sugarcoat it, and I hope you’ll bear with me while I vent.

It’s not just my tendon injury, which will take two to three months to fully heal, so I haven’t run since November 2. It’s that I took a psychological hit and stewed over the way my in-laws, with whom we spent Thanksgiving, chronically treat me like a bump on a log and talk past me, showing zero interest in my life and asking not a single question about what I’ve been doing. (They have not once, in all my adulthood, asked about or acknowledged my running, coaching, or writing.) The only question aimed in my direction had to do with a recipe. I leave their house feeling as if my only purpose in life was to support their son and produce their grandchildren.

They’re in their mid-80s, so I should let it be and make peace with the way they are, but missing my deceased parents makes me foolishly wish that my in-laws might in some way fill that role. Then I tell myself, it’s kind of ridiculous that at 55 I’m still seeking parental recognition and validation. I know I need to find that from within—and mostly I have, until I’m in a setting that makes me feel like an inferior twentysomething again—and I shouldn’t let my perfectly pleasant in-laws get under my skin.

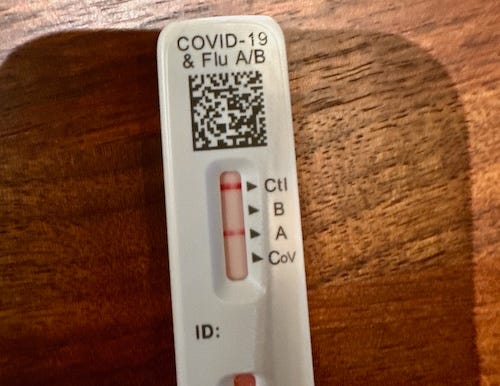

Compounding my funk, a couple of days after Thanksgiving, I got super sick with type-A flu.

I returned home Sunday after an all-day drive feeling all-over gross, achy, feverish, adrift, unable and incompetent to do anything, and in the worse shape of my adult life. My Garmin watch registered my HRV as off-the-charts low (indicating stress) and my sleep as “poor” and “non-restorative,” which I irrationally took personally as a sign that I’m a failure at resting. All Monday, with a temp of 102 that made me curl up in a ball, I drifted in and out of sleep with the pervasive thought, I can’t do anything. I felt weak and pathetic.

I’m sharing this not to gain sympathy, but to show how runners who can’t run, and who rely on running to bring a daily dose of accomplishment, structure, socialization, and mood-boosting sensations, operate like a broken compass and repel like expired milk. In other words, you can tell there’s something really wrong and off-putting about us when we’re not running. On the surface, we’re simply coping with not being able to run due to injury and/or illness, but deeper down, the not-running evokes dark moods with darker emotions of fear and insecurity.

The fact I’m writing this on Tuesday afternoon means my fever broke and I feel more functional (thanks to starting Tamaflu anti-viral med, trying to fast-track recovery to be well enough to travel on a big trip that starts this weekend). But I’m struggling to shake this pessimism.

In a nutshell, I’m worried I’ll never feel really good running again—I won’t feel like myself. I worry that the successful seven days in the desert in September, for which I’m deeply grateful, might have been my last ultrarunning hurrah.

My orthopedist had a wait-and-see attitude about my MRI results that was not particularly reassuring. The tendon attachment might feel fine next year, or it might flare up again—can’t be sure. He suggested I get a PRP injection, which might help, but it might not.

Uncertainty challenges me deeply. I don’t like being in limbo. And I suck at resting.

Grasping for a thread of positivity, I thought about how this time off from running motivates me to start again and wisely rebuild fitness. Often this time of year, I feel burned out from the year’s training and happy to reduce running volume, and to experience the mountains in other ways such as skiing or ice climbing. Often I have to work to get my running mojo back.

The opposite is true now—I want to run so much. I’ve got plenty of desire and motivation, but not the physical capability.

Another silver lining: This is an opportunity to work on my life outside of running—my writing, reading, relationships, back-burnered projects, nonprofit work, and soon I’ll be on a great trip to Ecuador and the Galapagos, so who am I to complain? I know, I know. The problem is, my mental acuity and confidence suffer when I can’t run. I really do feel like a bump on a log.

Objectively I know I’ll feel better once I’m healthy. But I want to document this low point for anyone else who can relate, and as a reminder to myself when I feel better not to take it for granted.

I credit

in part for inspiring this post, because her candor in her newsletter a few days ago helped me open up:

Wanting to share something with you all that’s actually useful, I scanned my old blog for some evergreen content to repurpose and found this post about three favorite workouts that help reignite a spark by tapping into curiosity and desire. Let me know if you try them and how you like them!

Three favorite run workouts

I love these because they’re unusual and mix up routine. They’re a sure cure for any running “blahs.”

1. The Boot Camp Hill Run

A hill workout with plyometrics mixed in, intended to develop strength, cardio, and agility. Choose a route of approximately 5 to 8 miles (depending on your fitness level and time available) that features a mix of challenging but runnable hills—hills steep enough that they spike your heart rate and fatigue your legs, but you don’t need to downshift to hiking. Ideally the route is bookended with a stretch of mostly flat, gentle terrain for warmup/cooldown. You can adapt this workout to a treadmill by keeping the flat portions at 1% incline and then, after the first mile, elevating the incline to 4 - 6% for a half mile of slower uphill running, followed by a half mile at 0 to -3%, to simulate hills.

Run nice and easy at a conversational pace for approximately the first mile. Then, every time you reach the base of a hill, work the uphill with extra effort, elevating your breathing to the point where you can only say a few words at a time—about an 8 on the Rate of Perceived Exertion scale. Use the downhills to catch your breath and aim for relaxed, smooth-flow downhill running (don’t “hammer” the downhills!).

Now here’s the fun part: Every time you finish a mile, pause your watch and do an exercise on the following list. (If your route is less than 8 miles, then combine some of these exercises after each mile so you get all seven done mid-run.) Google these exercises for video tutorials if you’re unfamiliar with them.

a set box jumps with reps to fatigue (try 15 to start); find a low wall, jump up and land with bent knees; step back or jump back down

a minute of alternating bodyweight squats & jump squats

30 seconds of “apple picker” skipping, with the bent knee rising up to hip level and arms swinging high to sky, followed by 30 seconds of grapevines

a minute of jumping jacks

a set of one-legged squats on each leg—full pistol squats if you can do them, or modified by lowering on one leg to sit on a bench then standing back up on that leg without using hands—slow and controlled while focusing on balance; reps to fatigue

Find a bench or low wall and do a minute of step-ups, alternating each side; the non-standing leg’s bent knee should come up to hip level, and arms should pump as if you’re running

Find a spot on the ground where you don’t mind putting down your hands, and end with a set of burpees. Go for 12 at least.

Get creative and add different body-weight exercises to the mix.

2. The Pick-Your-Poison Speed Session

An interval session intended to tap into your internal motivation and to fine-tune your sense of pacing. I recommend doing this workout on a mostly flat, uninterrupted path such as a bike path, since you will be doing timed intervals rather than measured laps around a track, and a path with some variations better simulates road and trail racing. But, you can also do this workout on a track or a treadmill if you prefer.

For runners accustomed to regular speedwork, I recommend a goal of 20 minutes total of fast intervals. Less experienced runners can do 12 to 15 minutes total intervals; runners with a higher training volume can go for 25 to 30 minutes. But 20 minutes is a good target for a solid session.

Run at least a mile easy for warmup. After your warmup mile, throw in a set of 6 x 30 second strides (surging toward sprint) with 30 second recovery after each, to get your legs and lungs primed for the speedy intervals to come. Run easy until you feel fully recovered from those strides. Now you’re ready to start the meat of the workout.

The goal is to run a total of 20 minutes at what feels “fast” for you, with the speed depending on the length of the intervals. Here’s the catch: You decide the mix of intervals. Ask yourself, “How do I feel like running hard today? What combo of intervals feels most motivating and exciting?” It can be any combo that adds up to 20 minutes (or whatever your goal total for minutes is), such as 10 x 2 min, 4 x 5 min, 2 x 10 min, or (my personal favorite) a ladder such as 6, 5, 4, 3, 2 min. It could even be a 19-minute tempo interval followed by an all-out 1-minute sprint. You decide the mix that feels most interesting and exciting to you.

The shorter the interval, the closer to max effort you push. You should run a pace that’s sustainable for the whole duration of the interval, so that you don’t “redline” and blow up mid-interval; but, it should be hard enough that your breathing elevates to the point where your ability to talk is limited to a short phrase, and you feel relieved and ready to be done by the time the interval is over.

Your recovery time between intervals should be 2 to 3 minutes (unless it’s a very short interval, in which case a 1 minute recovery should suffice). Let yourself take enough time slowly jogging between intervals to let your heart rate lower to the point where you can talk again, and you feel stoked and perhaps even impatient to start the next interval.

This exercise fine-tunes your intuitive sense of pacing, because rather than trying to hit a specific number for a precise distance at a track (e.g. 800 meters in 3:15), you are running by feel and aiming for as close to perceived max effort as you can sustain for the duration of the interval—a skill that helps you race hard, pushing your limits without surging too much too early.

After the interval set, run easily for the remainder of the run. Your overall distance will depend on your speed, the length of recovery between intervals, and the distance of your warmup and cooldown.

3. The New-to-Me Easy Run

An easy run to cultivate mindfulness, patience, and an exploratory mindset. This run is inspired by the “every single street” project started by Rickey Gates, who ran every single street in San Francisco. It also reminds me of when my dad used to drive me to junior high on his way to his office, and instead of being rushed to get there, we’d take extra time and try to find a slightly different route across our hometown of Ojai. “Let’s go find some cul-de-sacs!” he’d say with his bellowing laugh—neither of us really wanting to get to work or school—and he’d drive us down remote side streets, or he’d follow my directions to turn on a whim, and we might have to make a U-turn at a dead end. Those meandering drives, exploring every single street in Ojai with my dad, often were the best part of my otherwise tortured junior-high day.

On this easy run, aim for a pace that feels relaxed and could be sustained for a whole ultra—so easy that you could sing the “Happy Birthday” song out loud as you run. These lower-intensity easy runs below aerobic threshold are valuable for many reasons, helping you recover from and adapt to the stress of faster runs while also helping you develop the tortoise pace you’ll need for ultras. But they can be boring … unless, you challenge yourself to run like a tourist, finding and soaking in new sites.

This is the challenge: Go out your front door and run a route that’s at least slightly different from any run you’ve ever done before, for at least an hour solid. Which side streets, faint trails, or detours have you never explored? Find them.

A benefit to running someplace new-to-you is it probably feels like it takes longer, because it’s unfamiliar, and therefore it behooves you to cultivate patience and relax into the run for the duration. This is valuable mental practice for trail races that often will be on a route that’s unfamiliar to you.

One last thing

Are you on Bluesky? I’m trying to decide whether this platform is worth my time. I’d love to hear if you like it and why, and please connect with me there @ sarahrunning.bsky.social. (I haven’t posted yet, I’m just lurking and learning.) Mostly I’m active on Instagram, Substack Notes, and I dip into LinkedIn about once a week.

Thanks for sharing what you did. Family stuff is tough. My mom wasn't an easy person and it took me years to realize the approval I so craved would never come. It was a similar dynamic you describe with your in-laws. After she died, I remember discussing some of the dynamics with one of my Aunts. She said, "she was jealous of you." It startled me. Never in a million years would I have thought that, but once someone verbalized it, it made a certain amount of sense. I also came to realize my mom's way of "supporting" me was through material things and not emotional things. It's all so complicated when all you want is the simplicity of love.

I SO RELATE.

Not knowing if or when I will ever run again while most of my life and relationships involve running is challenging.

Hang in there. What you do and who you are makes a difference in my life.