Welcome back, and thanks for being here. This week, I’m mostly offline at a writers’ retreat in Taos hosted by

. To focus on my writing project there, I prepared this post ahead of time. It’s a guide to a special trail network and wilderness area near where I live, with a connection to my past.First, I’ll share a couple of links to archived posts that new subscribers might find worthwhile if you missed them earlier.

I’m at this retreat to work on fulfilling a goal I shared in this new-year’s post. (Remember those goals and resolutions from five months ago? Do you ever think of them now?)

Two Big Questions

What do you need to feel whole? What do you want to do before you die, in case you die next year?

I have a birthday coming up soon, and last year, I had an epiphany about birthdays. This post if for anyone who feels ambivalent about their birthday and struggles with aging:

Why Bother with Birthdays

For the last several years, I’ve minimized my birthday and let my family fold it into Mother’s Day, which falls on or near it. My birthday felt like a bother. Then it hit me, I’m devaluing myself and denying aging ...

And if you plan to visit southwest Colorado, you may find this post helpful, in addition to the trail guide below:

Essential Travel & Trail Tips for Telluride, Ouray, and Silverton

With summer approaching, now is the time to make plans and reservations if you’re planning to visit southwest Colorado, especially Telluride and its surrounding towns.

A Special Section of the San Juan Mountains

A version of this piece originally appeared in the July/August 2023 issue of UltraRunning magazine under the headline, “Trails Lead to Alpine Lakes, 14ers, and the Past.” Please subscribe to UltraRunning, it’s worth it! (I write a column there, too.)

When it’s summertime in the San Juan Mountains of southwest Colorado, I frequently run one of the gentler trails in the region, the old Groundhog Stock Trail where cowboys used to herd cattle and sheep to load onto rail cars. The railroad is gone now, leaving in its place a dreamy path south of Telluride called the Galloping Goose Trail that connects to a network of trails known as the Lizard Head Wilderness.

The San Juans beckon runners and Hardrock-hopefuls from around the world, and I feel blessed to live here and traverse the high-alpine trails above Telluride, Ouray, and Silverton.

For those ultrarunners who visit, I have a tip: don’t focus exclusively on the routes and peaks that form the Hardrock 100 and Ouray 100. Go a little farther southeast to discover the 41,500-acre Lizard Head Wilderness area. While this subset of the San Juan Mountains is well known to climbers and hikers, fewer runners seem to make their way to this area.

As a mountain runner, I appreciate the diversity of the routes that skirt Lizard Head Peak. Unlike the mountainsides that form the box canyons behind Telluride and Ouray, where the trails switchback straight up and are nearly impossible to run, the lower-elevation trails around the Lizard Head Wilderness are comparably flat and rolling.

On one side of the stock trail, three 14ers rise majestically—Wilson Peak, Mount Wilson, and El Diente—with a chimney-like volcanic pinnacle named Lizard Head sticking up like a giant thumb. On the other side of the trail, across Highway 145, Trout Lake spreads out like a mirror, reflecting more peaks. If I could sprout wings and fly directly east over those mountains for about 15 miles, I’d land in Silverton.

This trail’s high-alpine wildflowers, forests, and snow-streaked talus slopes tug at my heart, but something deeper than the aesthetics and sensations of the wilderness rev my emotions. I get the feeling I’m running into the past to commune with my ancestors on my dad’s side by following in their footsteps. Sharing this trail that they used to ride, in this backcountry area where they worked and played, helps me feel closer to them.

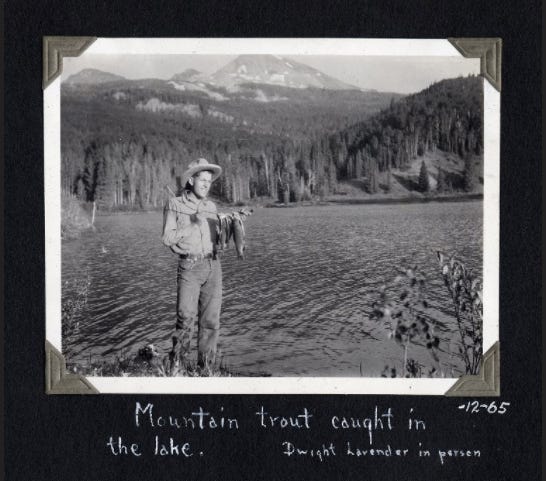

My grandfather David and his brother Dwight used to ride horses down this trail to move their stepfather’s cattle back in the late 1920s and early 30s. They were part of the last generation to conduct old-fashioned seasonal livestock drives before fencing, grazing laws, and trailers forever changed the trade. They’d ride for two or more days from Ed Lavender’s summer ranch near the Lone Cone, a mountain on the far side of this trio of 14ers. I try to picture them in the saddle, chasing down wayward cows and cooking simple meals over a campfire, using provisions carried in their saddlebags.

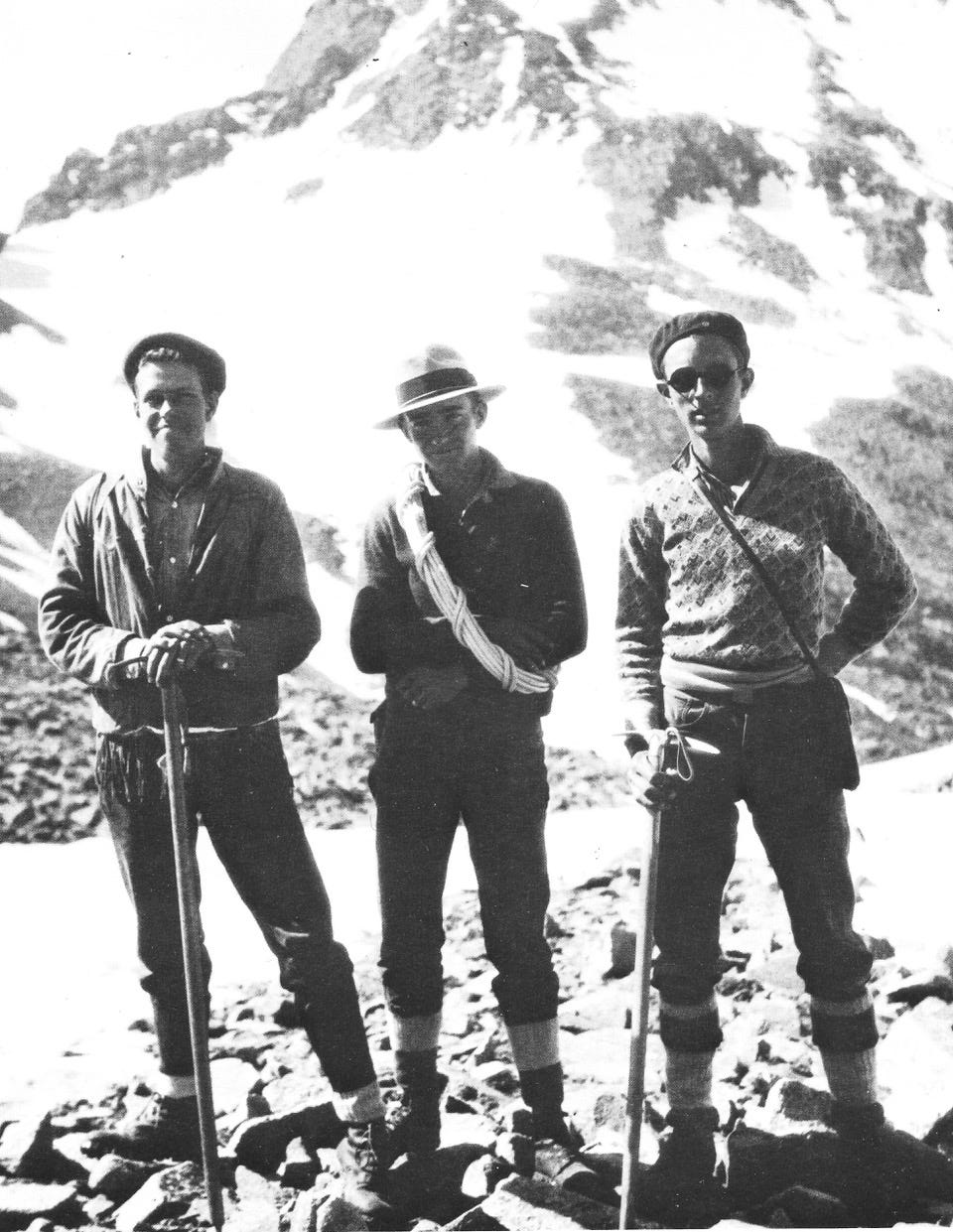

Then, as if predecessors to today’s dirt-bagging mountain athletes, they’d spend precious free time climbing and exploring these mountains. They probably didn’t run like I do—unless they were hustling down to a lower elevation while being chased by an electrical storm—because they wore calf-high, thick leather hobnail boots for traction while climbing, and each boot weighed nearly three pounds.

My grandpa’s brother, Dwight Lavender, became a famous mountaineer by climbing, mapping, and documenting first ascents of many peaks in the San Juan Mountains. He even named El Diente (“the tooth”).

On my runs in this area, which transition to hiking as the air grows thinner and the slopes steeper, I ascend above tree line on either the Cross Mountain or Lizard Head trails to approach the base of the 13,113-foot Lizard Head—which doesn’t look much like a lizard’s head anymore, but might have in the 19th century before rock broke off and changed its appearance. Craning my neck to gaze at it, I try to summon the bravery and adventure my great-uncle and grandpa must’ve felt when they climbed it in 1931. They were only the fifth climbing group to summit it after the legendary Albert Ellingwood made the first ascent on record in 1920. Today, it’s still considered one of the more difficult 13ers in Colorado due to its unstable rock and a pitch ranked 5.8 in difficulty.

At age 20, my great uncle Dwight made it to the top, with grandpa Dave tagging along to take photos and shout encouragement from the base. In an article for the October 1931 edition of the climbing magazine Trail and Timberline, Dwight described the summit with understated toughness tinged with sarcasm:

“At a pinch, the top might be about the size of an average dining table. … The final rope-off, the worst of them all, grimly awaited us. It was necessary to tie the two [ropes] together, and this I carefully did and shouted down to Dave to see if the ends reached. He informed me they were caught on the cliff, but that he was sure they would reach. It is such a pleasant feeling to be clinging on the face of a rotten cliff far above terra firma and wondering if your rope will reach the bottom or miss by ten feet or more. … I never can hope to tell you how it feels to back out over the brink of a high cliff when starting to rope-off. It is like stepping out into nothing, and the rope seems like such a slender thing between you and destruction.”

You don’t need to be a climber with ropes to appreciate Lizard Head and its surroundings. In the decades that followed these earlier exploits, the stock, railroad, and mining routes crisscrossing the area developed into a relatively runnable network of trails connecting lakes and summits.

My favorite Lizard Head Wilderness loop is approximately 12 miles and combines runnable rollers with gnarly hiking and starts at the Lizard Head Pass trailhead along Highway 145 near Trout Lake, 16 miles south of Telluride. Ascend Lizard Head Trail in a counter-clockwise direction and soon you’ll be switchbacking up to the ridge of the 12,150-foot Black Face Mountain.

This elongated ridgeline—thankfully, more runnable than technical—offers one of the best panoramic views in all of southwest Colorado. You’ll see Lizard Head flanked by Gladstone, Mount Wilson, and Wilson Peak. (Yes, there are two Wilsons next to each other, named after A.D. Wilson of the Hayden Survey, causing chronic confusion over which is which. The throne-like Wilson Peak, visible from Telluride, is the one made famous for being sketched on the Coors beer can, whereas Mount Wilson is tucked behind it and connected by a ridge to El Diente.)

Looking northeast, you’ll see Sunshine Mountain and the San Sophia range ringing Telluride; then, farther east, Yellow and Vermillion peaks and other mountains leading to Silverton. Hardrock’s infamous Grant Swamp Pass lies just over this eastern ridge.

From the top of Black Face, Lizard Head Trail runs down a ways, rejoining forest and meadowland, then goes back up above the tree line, through tundra and scree, to the base of Lizard Head. Eventually, you’ll meet the intersection with the Cross Mountain Trail.

Here, you could go right and continue the Lizard Head Trail to the north side of the wilderness area, past the old Morningstar Mine and along Bilk Creek, but I prefer to turn left and descend Cross Mountain Trail, a joyously runnable downhill that takes you to the Cross Mountain Trailhead on Highway 145. From there, you can reconnect to the first trailhead, where presumably you parked, on an easy two-mile trail that used to be a railbed and parallels the highway.

Woods Lake is another jumping-off point to explore the Lizard Head Wilderness. The lake is about eight miles up Fall Creek Road, which branches off from Highway 145 near the town of Sawpit down valley from Telluride. In addition to running, I also trailer our horses there to ride. The Woods Lake Trail leads to Elk Creek, Rock of Ages, Wilson Mesa and Lone Cone trails, all worth exploring. But if I had to choose just one from Woods Lake, I’d probably follow Navajo Lake Trail to reach yet another glassy, gorgeous alpine lake.

When you’re ready to graduate from mountain runner to summit scrambler, I suggest Wilson Peak as the first 14er in the area to attempt. (It’s the only one I’ve done, because Mount Wilson and El Diente are more difficult. Read here, “How I Finally Climbed the King of the San Juan Mountains.) I also suggest hiring a guide if you’re inexperienced like me, in case you need to rope in for safety if the summit approach is icy or slippery from snow.

I grew up camping, fishing, and hiking every summer at Woods Lake with my family, and I trace my love for mountains to this wilderness area. Based on the photos my great uncle and grandpa took of the area some 90 years ago, and my own childhood memories, the wilderness remains remarkably unspoiled.

I’ll be back next week with fresh content, including some reflections on the experience of being the single lone voice expressing support for a conservation proposal in a large angry crowd; plus, how some lessons from this weeklong writing retreat also many help the practice of running.

If you would like to support this newsletter but would rather not commit to a paid subscription, I invite you to make a small donation to this virtual tip jar.

So awesome. I remember North Star and quandary from my Breckinridge days