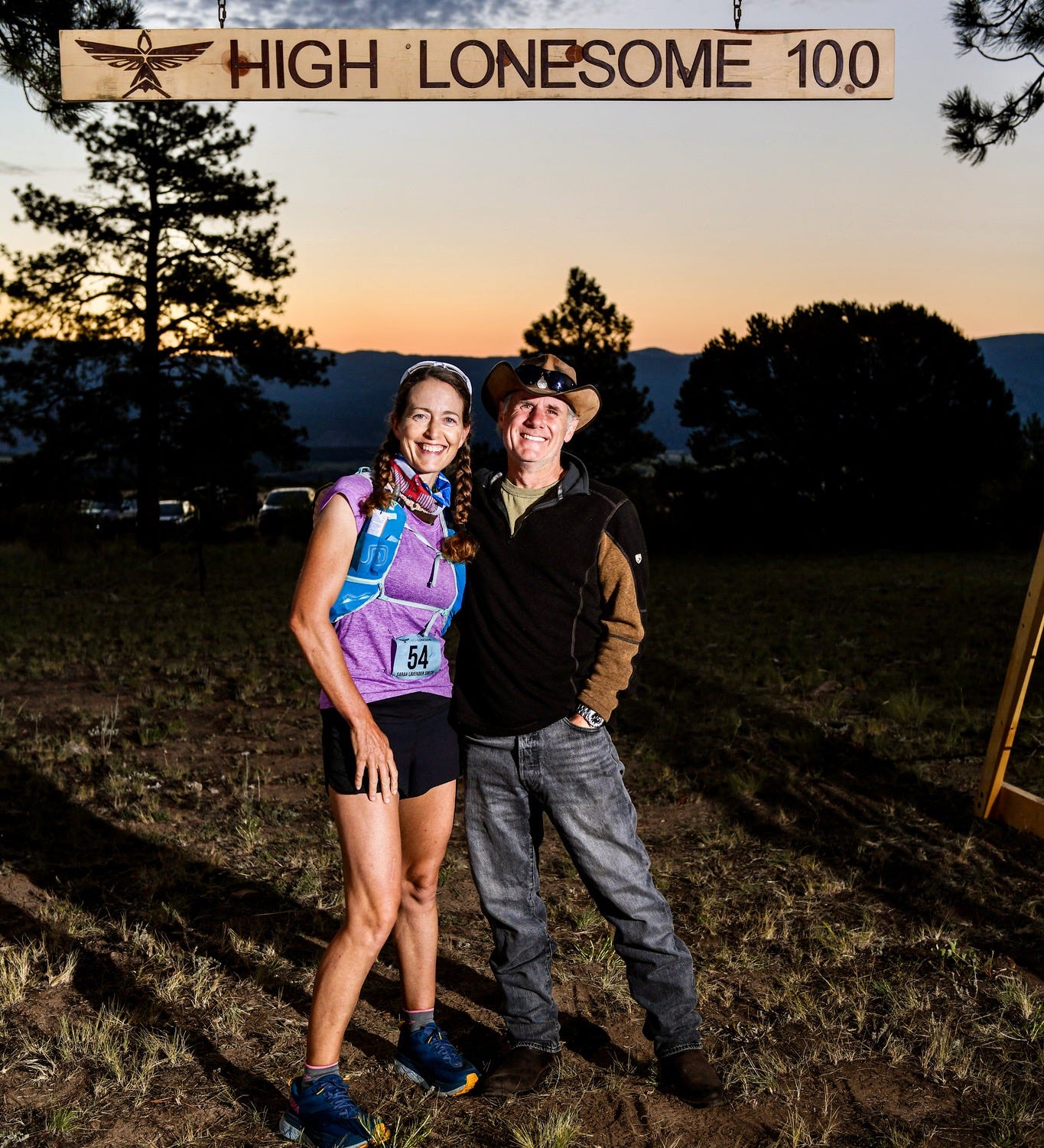

I tried to write about last weekend’s 100-mile race as soon as I got home. But coherent thoughts weren’t happening. After I crossed the High Lonesome 100 finish late afternoon on July 23, I could manage only the simplest tasks—shower, foot care, reorganize gear. Long drive home. Sleep—all I wanted, to sleep. And gradually, carefully (after so much nausea), eat. My body consumed cheesy scrambled eggs with avocado as if malnourished.

Then laundry, so much laundry. Animal care. House cleanup. Email—way too much. I felt so braindead and moved in such slow motion that I took another covid test. I got another negative result, thankfully. I dodged the virus and can’t blame my mid-race weakness and drowsiness on it. I was just weak and sleepy because—well, perhaps because I’m old and need my sleep.

I’ve always drawn parallels between 100-mile ultras that take months of training, and pregnancy and childbirth. After the ultra, exhaustion and a mild case of the blues can set in, not unlike the postpartum phase. I recalled and followed my friend’s sage advice from 2001 when I felt overwhelmed in spit-up-covered PJs while caring for a newborn as well as a toddler. Lower your expectations of what you can do in any one day, she said. Just showering and getting dressed while caring for the babies is an accomplishment. Eat and stay hydrated. Don’t worry about email.

It’s been over 20 years since I gave birth to my two kiddos, but as I ran, I reflected on being a mother and felt tidal waves of emotion about my kids growing up, about me aging, and about my mom dying. The odyssey of the High Lonesome 100 made me feel the passage of time and the love of my family.

I am certain I would not have made it to the finish without my husband Morgan, daughter Colly, and son Kyle, plus my pacer Gretchen. I would have dropped out after episodes of throwing up and feeling my gut clench with cramps as if I were a colicky horse. I would have remained splayed out on the forest floor, melting into the ground in spite of the rocks and bugs, rather than getting up to take more steps.

I need to attempt to articulate how and why those miles alternately felt so good, then so bad, before memory softens the experience—although, as with childbirth, the intensity of the pain immediately faded at the finish line, replaced by joy.

“God gave man a poor memory for physical discomfort,” my grandfather wrote after describing a miserable outing and overnight on the 14’er Mount Wilson in 1932 involving lightning, sleet, nausea, and exhaustion, culminating in relentless miles while “clambering endlessly through deadfall and under brush, falling into ravines, tripping on roots, wallowing knee deep in mountain bogs.”

When asked afterward if he liked the hike, he reflected why he answered “Yes, I liked it”: “The active ingredients which made the hurt so brutal at the moment lose their keen edge in retrospect; we are able to look back on them with a certain detachment and even make them subject matter of our dearest conversation pieces. … And so, I remembered Mount Wilson. Not the cold and the cruel fatigue, but rather the multitude of tiny things which in their sum make up the elemental poetry of rock and ice and snow.”

I could stop there, because my grandpa’s description sums up my High Lonesome race—a miserable, exhausting, nauseous experience, but in the end, I liked it. But that would be too easy, so I’ll try to capture some scenes as I puzzle over what went wrong. I need to figure out what I could have done better in case I reach my goal in the coming years of gaining an entry into the harder Hardrock 100.

An Auspicious Beginning

All systems cooperated in terms of sleeping, eating, going to the bathroom, driving to the start. We had done this routine last year for the 2021 version of the race, so we knew where to go and what to expect. I felt relaxed and ready.

Morgan made me laugh by telling me I had to finish so I would earn the bottle of high-grade whiskey given to each finisher, which he would drink. He would meet me at nighttime at the Mile 49 aid station, and the next morning at Mile 84. He mused about how he’d go to McDonald’s for breakfast without me, on his way to the aid station, because I hate McDonald’s. I laughed, grossed out, as he talked fondly about McDonald’s hash browns.

In my pocket, I had a Post-it note laminated with packing tape, and on it I wrote goal splits to each aid station. My overriding goal, beyond finishing, was to do better than last year, when I slowed so significantly in the second half. I would be a little more conservative in pacing the first half this year. The prior year, I had finished in about 33.5 hours. If all went well, I’d finish under 33 hours.

I hugged, fist-bumped, and said hello to runners I recognized: my friend Christina from Ouray who dropped out last year from severe nausea, Rachel Bell Kelley from back East who came to the region early to adapt to the altitude, a guy named Zach whom I’d met a month earlier at San Juan Solstice 50, and “outdoorable” Annie with her mentor Olga. They all looked confident, radiant, strong, and stoked.

Two would drop out, one would surprise me by finishing behind me when she should’ve been way ahead, and one would smash the course record. Hundred-mile ultras are unpredictable. It could be our best day, but probably won’t be. It’s impossible to tell at the start how the 100 miles, up to a time limit of 36 hours, will unfold.

At the crack of the gun, I took off running gently and relaxed with only one, albeit big, worry buzzing around my head like a bothersome fly: Would my kids and pacer get there OK? While I ran all Friday during the day, my daughter Colly (age 24) would fly from LAX to Denver, my son Kyle (21) would pick her up, and together they’d travel three hours south to meet Morgan in the mid afternoon. My friend and pacer Gretchen would arrive sometime midday too.

They’d rendezvous at our hotel by 6 p.m., and Morgan would drive the three of them to the Mile 49 aid station to bring me my preferred dinner food, help me change into nighttime clothing and gear, and then Gretchen would pace me through the night until Mile 84. And then, the next day—to my delight—my daughter would accompany me the final stretch to the finish, her first time ever sharing the trail with me like that.

But what if they had problems getting there? I couldn’t let myself think about a canceled airline flight, a car crash, a flat tire—all the things that could go wrong. I couldn’t control their day. I had to worry about myself.

No Pity Party

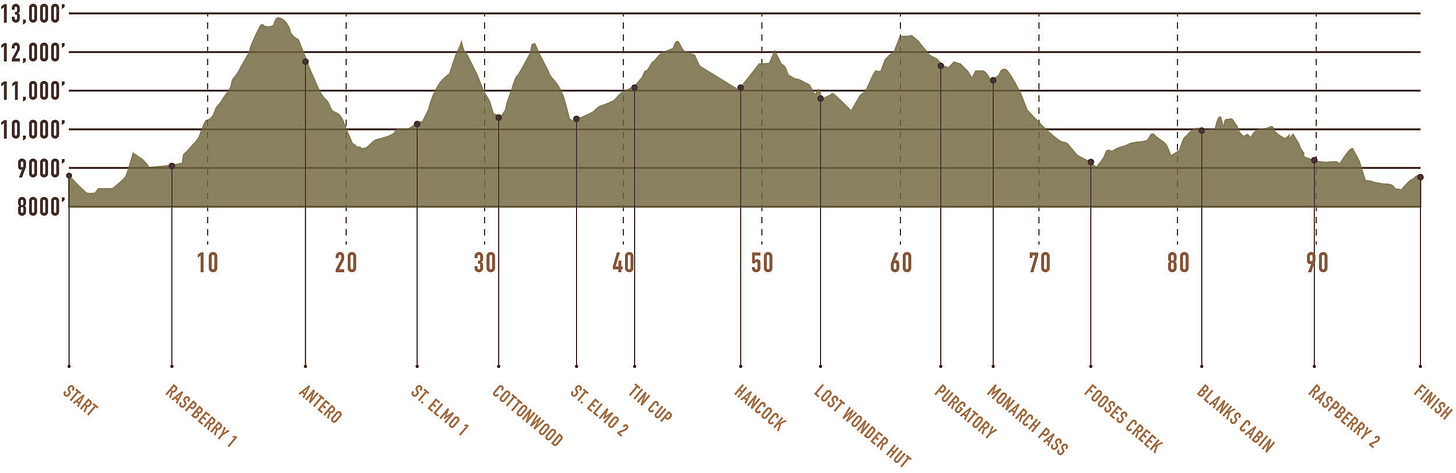

The first nine miles, featuring rolling terrain with one moderate hill, felt easy. Then the shit started getting real as we ascended to a high point of 13,100 feet skirting the 14’er Mount Antero and descended its backside on a mining road covered with ankle-rolling softball-sized rocks.

Midway up, I saw a man stooped over. At first I thought he was getting sick, then I realized he was doing something to his knee. A closer look revealed it was Dave Mackey adjusting his prosthetic lower leg.

I couldn’t believe I was leapfrogging with Dave Mackey, who loomed large back when I got serious about ultras. We’re both graying, both born in ’69. He was at the top of the sport in the mid to late 2000s, earning Ultrarunner of the Year in 2011. I ran behind him in the 2012 Miwok 100K and saw red open wounds the size of silver dollars on the backs of both of his heels, because his socks had slipped down and giant blisters erupted, but he went on to win that race for the fourth time. Dave Mackey, the legend.

And here he was, having survived a life-threatening accident in 2015 when his leg was crushed by a boulder during a run. Post amputation, he’d finished the 2018 Leadville 100. But Leadville is a smooth ribbon of trail. How would he handle High Lonesome’s terrain of rolling, jagged rocks?

I said hi and reminded him that we had crossed paths in the Bay Area. He remembered me and smiled, but he wore an expression of pain. I imagined that on top of physical pain, he might feel his ego’s pain from being back in the pack with average runners like me. I vowed then and there that however badly I felt for the remainder of this race, I would not feel sorry for myself. Be brave like Dave.

Around Mile 20, I connected with a woman who normally would run faster and farther ahead of me, Hilary Matheson. She was having a rough day due to cramps and the altitude. Plus, when you’re a fast runner and fall behind where you want to be in the field early in a race, it’s hard to stay positive.

We met a year ago through her boyfriend, the filmmaker Billy Yang. “How old are you?” I asked, and she answered 33, then she asked my age, and I said 53. I don’t think either of us realized our 20-year difference.

Hilary turned and put a hand on my shoulder. “Oh my god, I’m so impressed by you!” I laughed because I did not feel impressive, just dogged. I remembered in my early 30s when I had a female boss who was 20 years older, and that woman seemed so old.

As often happens during unfiltered trail conversations, we soon got on more intimate subjects—marriage and parenting—then circled back to the run. She was thinking of dropping, and I talked her back from that cliff.

“You just need to let go of expectations for today and make it a goal to finish and get your Hardrock qualifier,” I told her, naming a litany of notable runners who had hard-fought finishes at Hardrock and Western States. Those runners who struggle and finish much slower than their potential, rather than quitting, always earn my respect.

Later I would realize that our interaction helped me as much as it may have helped her, because after nightfall, I would need to listen to my own advice.

When she asked about my kids, I started gushing. They’re the thing I’m most proud about, way more than these ultras. She had tapped into my driving desire to see my now-adult children at our Mile 49 family reunion. But would they be there as planned? The anticipation and anxiety made me speed up, and gradually I pulled ahead of her.

Carnage

Law’s Pass is a mountain we cross twice in High Lonesome, on an out-and-back to the Cottonwood Aid Station between Miles 25 and 37. The pass tops out at close to 12,300 feet and rewards with sweeping views of the Sawatch range. This out-and-back segment is the most social, as runners pass each other in two-way traffic. It’s a chance to see who’s ahead and who’s behind.

Predictably, I was in the middle of the field. I was moving well at what felt like a sustainable pace, no major problems or pains, but I was 20 or so minutes behind my time at this point in the race last yer. When I got to Cottonwood at the 50K (Mile 31) mark, I lost more time because a new gear-check requirement made us load up with nighttime gear at this earlier spot. I fumbled trying to fit the required pants, long-sleeve shirt, and headlamp in my pack with other daytime required gear while also trying to choke down some food. The stop took longer than I wanted, and I felt the first onset of frustration.

Heading back out, the mid-afternoon warmth cooling with a cloud cover, I got to see all the runners behind me. Eventually I passed Dave Mackey, who was still making his way to the aid station, so I calculated I had at least a two-mile lead on him. He shook his head when he saw me and said, “rough day.”

“You’re brave,” was all I could think to say. He ended up dropping at Cottonwood.

I also passed my friend Christina, who was so ill with some combination of altitude sickness and nausea that she was lying on the ground. “Oh, shit!” I gasped with surprise when I stumbled upon her and reached out my hand to help her stand. I said all the reassuring things I could think to say as she retched, but my heart broke that her race would end early again.

It felt both sobering and fortifying to see others struggle along Law’s Pass. I knew I could suffer similar severe problems at nighttime or the next day, so I should keep going while I could. “Gotta make hay while the sun shines,” I said out loud.

The sun lowered in the sky. A strong but short-lived shower dumped, so I pulled out my rain jacket, then 15 minutes later I was hot and dry enough to tie it around my waist. I embarked on my favorite stretch of the route, from Mile 41 - 49, Tincup to Hancock.

Switchbacks ascended to the Continental Divide Trail above tree line, where we ran at close to 12,000 feet through spongy alpine tundra dotted by wildflowers. I could not run at this high of elevation for an extended time without taking hiking breaks to moderate my heart rate, but mostly I ran, uplifted by the views saturated in alpenglow.

I stopped only to talk to a woman in distress and hyperventilating. Her chin trembled, and she burst into tears when I asked how she was doing. She looked young, only in her 20s, and she probably didn’t realize she had chocolate smeared around her mouth like a little kid, so I felt maternal toward her.

“I left my puffer in the car,” she said, explaining she felt she couldn’t breathe. I encouraged her to take deep belly breaths to calm down. “You’re doing fine,” I said. “Try to let go of any self-criticism and expectations, and be proud of what you’re doing out here,” but that only made her cry harder, so I got her to focus on slowing and deepening her breath, encouraging her to relax her jaw and shoulders. “Thank you,” she kept saying. Eventually I ran on, grateful my own respiratory system was cooperating (as described in this post).

I moved at a good clip, each mile increasingly eager to reach the Hancock aid station, to see if my family and pacer were there. When I ran this last year, I reached Hancock just a couple of minutes past 8 p.m. This year, I’d have to push to get there between 8:30 and 8:45.

I didn’t want to make them wait. I didn’t want to arrive after dark. I was chasing sunlight. I ran harder on a runnable section of railroad grade.

Looking back, I wonder if my push in this section triggered too much stress and fatigue. Whatever, I got there without needing my headlamp, around 8:30 p.m.

The First Sign of Trouble

I heard music and the sounds of people cheering and ringing cowbells. Hancock, roughly the halfway point, is a major crew stop along the race route, so clusters of people crowded what’s normally a quiet camping area.

“Mooooommmmmm!” I heard my son Kyle, bellowing like the sports fan he is, and spotted him dominating the middle of the rocky mining road, arms outstretched. Relief washed through me as I let my youngest, who’s now three inches taller and 25 pounds heavier than I, envelope me. We hugged and swayed—if only he were this affectionate all the time!—and then he stepped back to get a look at me.

“Those glasses!” he said, a throaty uncontrollable giggle rising. He had not seen my new sports glasses before.

“I know, they’re totally dorky, but now I can see.”

“No, um, they’re … fire! Honestly, you look good!”

I looked past his shoulder to see Colly waving and bouncing on her feet, next to Morgan, next to Gretchen who was bundled up in nighttime running gear with a headlamp on her forehead. They made it!

Colly commanded, “We have everything ready—come sit!” I soon realized she was taking the role of crew and pacer seriously, and she was talking to me the way I would talk to her. But first, I wanted to hear about them and their day.

Colly told me, “It was fun, we had the best day! I’ll tell you about it later,” and she and Gretchen took charge of making me sit and take care of business. “You’ve got 20 minutes,” Colly reminded, referring to my race plan that stated I wanted to spend only 20 minutes there.

They had followed my instructions to bring heated macaroni and cheese and chicken noodle soup in Thermoses, plus cold La Croix sparkling water. First I wanted to change. I took off my shoes, and they held up a blanket to shield me as I pulled off my shorts and pulled on running tights. Kyle turned his back, and I joked, “Kyle’s worst nightmare—Mom exposing herself!” He laughed and helpfully transferred my bib from my short-sleeve to long-sleeve shirt.

I simply wanted to sit and talk, but we had so many details to handle. Eat, eat, I needed to eat! I hadn’t eaten much all day besides gels and sports drink. The trail mix and bars I carried in a pocket did not appeal to me on the trail—they made my dry mouth work too hard to chew—so I needed to get down this good pasta and soup.

I put some spoonfuls in my mouth. The mac and cheese tasted gummy and stuck in my throat, as did the soup’s canned chicken and carrots. I preferred to sip the salty broth, not chew chunks of food.

Morgan had brought a loaf of fresh-baked airy focaccia purchased a day earlier from a local baker. Kyle said, “The focaccia’s the bomb! You gotta try it!”

So I ripped off a piece of the bread and stuffed it in my mouth. Uh-oh, it tasted rancid and like the sourest of sourdough. “It’s so sour!” I said, and leaned over the chair to spit the doughball on the ground.

The kids said in unison something like, “No way, it’s not sour, it’s definitely not sourdough—it’s so good!”

But food to me—the big-eating omnivore who normally eats comfort food like mac and cheese as if it’s dessert—was not tasting good. I took a few more bites of soup and pasta but did not consume the dinner I should. Only the cold sparkling water tasted good.

I looked up at Gretchen, glad to see her—a runner friend for over a decade—and confirmed she was ready. It was around 9 p.m. and dark by the time we got through another gear check and said goodbye to Morgan and the kids.

I was ready for the night—but also, feeling more deflated than energized after the first half of the race. So much anticipation and emotion went into meeting my family at the Hancock Aid Station. I needed to get out of mom mode and be the athlete I wanted to be.

At least I could look forward to meeting them the next morning at Mile 84, the aid station called Blank’s Cabin, where Colly would take Gretchen’s job of pacing.

We made our way up another rock-strewn mining rode to a single-track trail, pausing frequently to adjust our lights and gear. I felt clumsy. I needed to refocus to nail one of the hardest sections of the route ahead—the steep portion from Lost Wonder Hut (Mile 55) to Purgatory (Mile 65).

I needed to get through the night.

Continued in Part 2 here.

I'm clinging to the edge of my seat! Totally loving this account as I wrestle with my own feelings of tackling a hundred miler.