Thank you for reading my weekly newsletter. If you haven’t subscribed, please do. Next week, I’ll spotlight ultra training, as I’m 10 days from the San Juan Solstice 50 and five weeks from the High Lonesome 100. This week, I hope you’ll find inspiration as well as heed the cautionary advice in this summer camping post.

I am not a hard-core camper or backpacker. Give me a reclining chair, a trusty two-burner camp stove, and a cooler full of cans of sparkling water and beer, and I’m a happy camper.

I sometimes catch myself feeling I should develop into a backpacker. As a fan of Wild and an admirer of friends who spend overnights in the backcountry, far from any vehicle, I experience an urge to go to REI to rent or invest in a proper backpack and lightweight gear, so that I and my husband could traverse a trail for multiple days self-supported.

I went on backpacking trips in high school and early adulthood, and I’ve excelled at self-supported stage races during which I must carry food and gear to last a week, so I know I can do it. It’s a matter of wanting to and making it happen.

Inevitably, my desire fizzles when I start planning. How much easier and nicer, I conclude, to car camp and then wake up near a trailhead, ready for a morning in the mountains. I don’t want to hike slowly with shoulders aching from a 30-pound pack. I’d rather stash stuff in a vehicle and traverse a trail with just a hydration pack and safety essentials.

I’m therefore writing in appreciation of the experience that’s in between backpacking and towing a camper on wheels: car camping. Here’s why and how.

Why camp?

Camping takes effort. Researching a destination, then assembling gear and food for one or more overnights, means breaking out of a comfortable, predictable home routine.

I knew it would be healthy for Morgan and me to get out of the house, out of cell range, and spend the night in the woods because we’ve both been overly preoccupied with work and projects. Camping off the grid, unplugging from devices, sitting in the crisp air while listening to birds and gazing at stars, then hiking together the next day would be a mini retreat to relax and reconnect.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve driven by a turnoff on the outskirts of Ridgway that points to a recreation area, but I had never driven that way. The sign says Owl Creek Pass and Silver Jack Reservoir. The trailhead for a mountain I want to summit, Courthouse, is out there. So, I told myself, “No time like the present.” It was time to check out that area and get up that mountain.

We lined up animal care and made a pact to get out of the house by 2 p.m. Friday, which would get us to camp around 4:30. We had to scramble and leave some work undone. But we made it. I was reminded that car camping isn’t hard—you just gotta get your shit together and go. I vowed to do it more often.

Setting up our familiar old tent, our four hands working together to thread the bendy metal poles through loops, then sitting on the ground at dusk across from one other to deal cards and play a hand of gin rummy, I felt a sense of relaxation and companionship I don’t always feel at home, where chores and projects demand attention and relaxing means tuning into the TV rather than into each other.

What to bring (hint: it’s OK if it’s old and heavy)

With car camping, you can take pretty much whatever you want. For us, that means a heavy tent carried in a duffle—our almost-vintage dome tent that’s around 20 years old—sleeping bags and thick, body-length pads; a big cooler; a camp stove, pots and pans, dishes and utensils; extra water; a folding table, chairs, lanterns, books, extra clothing, toiletries (don’t forget bug spray), first aid, and lots of food. (See below for a no-fail camp dinner recipe.)

Remember to bring a trash bag to pack out all trash, and a shovel or portable toilet since pit toilets may be locked for the season or non-existent for dispersed camping spots. Bury your poop and pack out your soiled toilet paper to leave no trace.

Car camping means parking along a road and therefore sleeping fairly close to a road. Never degrade nature by driving off road; keep your tires on the road or on pullouts.

The perfect spot with no one else in eyesight or earshot usually proves elusive for car camping during summer months. At the Silver Jack Reservoir, the main campground was closed (it opens later this week), so we and others had to jockey for good spots next to rugged road spurs off the main road. We settled on parking next to a lovely meadow ringed by an aspen grove, in view of a mountainside with rock pinnacles. Another person parked an RV about 200 meters away, but they were quiet and respectful, thankfully.

After we unloaded and got comfortable, the melodic birdsong that floated from the aspen grove soon put Morgan to sleep.

The annoying buzzing of a yellow jacket and the roaring of distant motors down the road momentarily bugged me, but I chose to focus on the birdsong. The same thing happened in the morning: Some idiot somewhere nearby decided to film the sunrise with a drone, so the drone’s buzzing filled my ears, but the birdsong soothed me and the drone eventually buzzed off.

Brief interferences from other people are to be expected while car camping and didn’t ruin the overriding peacefulness of being out there.

Campfires no more

I grew up enjoying weenie and marshmallow roasts over campfires with my parents and older siblings, who taught me to whittle a fresh aspen branch into a point to use as a skewer. Summer camping always involved a campfire, the focal point and gathering spot for the night.

The tradition is so interwoven with camping that, I admit, I didn’t hesitate to build a small campfire at our spot last Friday. Our camping area seemed safe with nothing flammable nearby—just fresh grass, dandelions, and young, calf-high skunk cabbage. The green aspen grove stood a good distance away, no distressed dry pine nearby. The air was still, the high winds having died out for the afternoon and evening.

The campers in the distance had a fire going. We didn’t read anything about campfire restrictions on the recreation area’s website. We didn’t see any info posted on the way to the campground. And so, we enjoyed a fire, even though it was unnecessary—we were warm enough without it and had a propane stove to cook.

It may have been my last campfire ever. In hindsight, after four days of extreme windstorms and a devastating fire breaking out near Flagstaff, Arizona, which generated enough smoke to hide the mountains around us in haze last Monday, I feel guilty that we risked any campfire.

On Saturday afternoon, I briefly posted a photo on my Instagram story of me next to our campfire, and a friend read me the riot act, messaging me that I was crazy to have a fire in these conditions. I deleted the photo as soon as I heard from him and told him, he’s right, I was sending the wrong message. To which he further excoriated me, “The ‘wrong message’? Sounds like ‘wrong behavior.’ I’m sure everyone who has started a wildfire was just as confident as you were in determining fire conditions.” He also pointed out that we were using a less-safe shallow fire pit ringed by rocks, rather than a safer, deeper pit ringed with metal or concrete, which developed campgrounds use.

I understand his anger and worry. Over the past two summers, as our region experienced an uptick in the Invasion of the Sprinter Vans, I’d drive down the county road near our house and spot clueless campers parked roadside with a campfire burning next to their van, in spite of a campfire ban. The road runs through a canyon choked with dead and distressed pine that could ignite with a single stray ember. I’d slam on my brakes and yell at them through my car window about the risk they were taking.

Every time I initiated this confrontation, the camper looked sheepish and apologetic and promised to extinguish it. Now I’m the one who feels sheepish and apologetic.

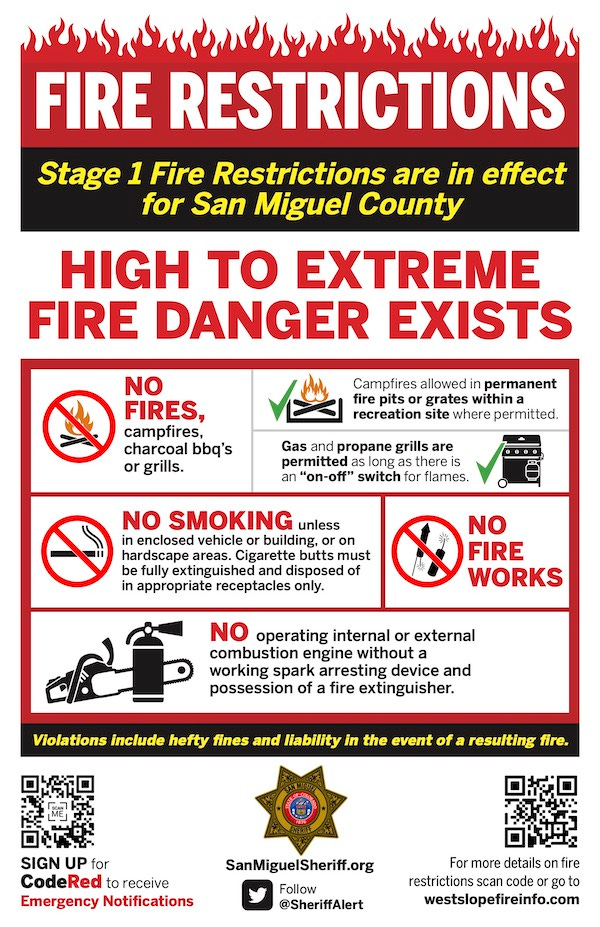

My friend and I had a constructive back-and-forth in which we realized the patchwork of county-by-county and statewide communication around fire bans is flawed and confusing. For example, over the hot, windy weekend when the National Weather Service issued “red flag warnings,” some sheriffs in some counties posted notices via social media to ban burning (but they did not, it appears, get out the word elsewhere—thus erroneously assuming that campers off the grid would be checking a sheriff’s Facebook or twitter). Sheriffs are authorized to impose immediate fire restrictions on open fires and fireworks.

But a temporary ban on burning during a red-flag warning is not the same as a Stage 1 or 2 countywide fire ban, which is longer term and leads to reporting of fire restrictions on this statewide site. This site by the Colorado Division of Homeland Security & Emergency Management, which one will find with an online search for info on campfire rules around the state, showed “no fire restrictions reported” in the counties in our part of the state over the weekend, even though these same counties had temporary bans in place because of the red flag warnings.

It took until today, June 15, for our county and neighboring counties to go into Stage 1 fire restrictions. And yet the statewide site lags in updating their info about the county-by-county restrictions, and the US Forest Service webpage for the campground we visited still doesn’t say anything about a campfire ban. The brochure for the area says, “keep campfires small, only burn dead and down wood.”

More public info and consistent messaging is needed to get the public to understand that campfires are not OK anytime, anywhere over summer in states suffering extreme drought. (Stage 1 restrictions ban the kind of campfire we started in a rock pit but still allow campfires in permanent pits in designated campgrounds “where permitted,” whereas Stage 2 restrictions prohibit fires in permanent pits, which is confusing, right?)

Why wait until the conditions are past the point of tinder-dry; why not impose the Stage 1 restrictions statewide starting Memorial Weekend?

As I said above, we didn’t actually need our campfire, we just lit it out of tradition and because it seemed safe where we were. It’s just not worth the risk.

Bagging a peak after breakfast

After a good night’s sleep, and coffee and oatmeal prepared on our stove, we checked out the Silver Jack Reservoir up close, built in 1967, and looked in the distance at blocky Courthouse Mountain, elevation 12,152, and the tall Chimney Rock next to it. Then we broke camp and drove about a half hour to the trailhead.

I had never explored this part of the Uncompahgre Wilderness and loved the relatively healthy, verdant forest, the strong flow of the Cimarron River, and the first blooms of lupin and other wildflowers.

We knew from research and word-of-mouth that summiting Courthouse is short but steep, and relatively easy as far as peak-bagging goes. It’s a mere 1.8 miles up from the trailhead but gains about 1700 feet in that short distance. We went up up up, pausing to marvel at the variety of geology—some hard granite, some soft sandstone, and some parts that looked like small rocks mixed with concrete, which must be remnants of an ancient riverbed uplifted.

In spite of my mountain experience, I remain fearful of heights and exposure, always worried my feet may slip out from under me on the scrabbly rock. I therefore took deep breaths and went extra slowly near the summit to ascend the rock, and to prevent slipping in slick muddy patches where snow had just melted.

Eventually, I got to the top and averted catastrophe, and I managed to get back down by doing a lot of crab-walking (my hands as well as feet easing me down the slope, butt-scootching mixed in).

We were rewarded with views of the mountains ringing Ouray as well as a bird’s-eye view of Ridgway and the surrounding ranch land.

I remember last October, on this training run, looking northeast and seeing Courthouse in the distance and promising myself I’d get there, someday. How satisfying it is, eight months later, to make “someday” happen.

No-fail camping fajita quesadillas

For an easy yet tasty car-camping dinner, try this:

Pack a stove and two sauté pans

Fresh tortillas

Grated cheese

Can of refried beans (don’t forget a can opener)

Store-bought guacamole or fresh avocado

Salsa

Onion

Red bell pepper

Chicken (or other protein of choice; tofu works)

Fajita seasoning

A little oil

Wash and cut up the meat or tofu ahead of time at home and slice the onion and bell pepper. Combine the protein, onion, bell pepper, fajita seasoning, and little oil in a bowl to mix, then transfer the mixture to a heavy-duty Ziploc bag. Pack it next to ice in the cooler. This way, the messiest and hardest part of preparing the meal is done at home, and it’s ready to cook at the campsite.

Use one of the frying pans to sauté the fajita mix, the other to heat the tortillas with beans and cheese on top. Tip: Instead of bringing a pot in which to heat the beans (which is difficult to clean while camping), just spoon the beans directly onto the tortilla; it’ll get warm enough that way.

Put the cooked fajita mix on top of the beans and cheese in the tortilla, top with salsa and guac, then fold over to make a fajita quesadilla and eat like a giant taco.

That is my no-brainer concoction. For creative and more elaborate camp recipes, check out this book Best Served Wild by Brendan Leonard and Anna Brones.

Yes 'lil sis, I remember those weenie & marshmallow roasts when we were kids. We were aware of Smokey the Bear & fire danger