I fit in one last mountain run this season before snow comes and makes the high-country trails impassable. I drove an hour from home to Ouray to meet a friend, Christina, who became a training buddy as we both prepared for the 2021 High Lonesome 100.

A day in Ouray—the touristy town with the hot springs pool and the roaring waterfall plunging down rock walls that form its box canyon backdrop—always feels like a special day, a feeling that harkens to childhood.

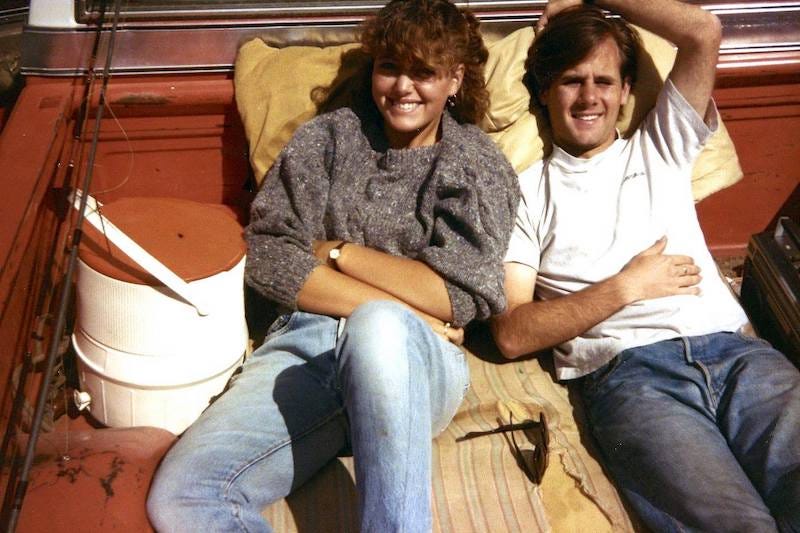

I got to know these San Juan Mountains in the 1970s in the back of my dad’s Ford truck, on daylong family outings over single-lane, high-clearance roads built by 19th-century miners and taken over by Jeeps a century later. My older siblings would put a mattress in the back of the truck, Dad added fishing poles, Mom made a picnic, and I—the youngest of five—would climb into the back with my teenage sibs to sit and bounce while we traversed these rocky roads. We had no seatbelts and no rain protection, except for a smelly green tarp we’d huddle under during downpours.

Dad would drive over Imogene, Ophir, Engineer or other mountain passes, and I’d ask, “How long ‘til Ouray?” because the reward for enduring the back of the truck was arriving at the Ouray Hot Springs pool.

I got to know Ouray more thoroughly in the summer of 2018, training for the Ouray 100, a ridiculously difficult route with over 41,000 feet of elevation gain. Because of the canyon walls and a route that tags 14 high points, you’re almost always either ascending or descending 3000 to 5000 feet. (I DNF’ed that race at mile 60ish—one of two times I failed to finish an ultra in the past 15 years—and that failure gnaws at me still.)

It was that summer, thanks to Ouray, that I more fully evolved from trail runner to mountain runner. What’s the difference, you might ask?

Trail running and mountain running both involve locomotion on unpaved routes through a natural environment. But mountain running, a specialization of trail running, is more challenging because the mountainous environment features thinner air, sketchier terrain, and more variable and extreme weather. Mountain running, more so than trail running, employs and embraces hiking as a slower gear of running, because so much of the terrain and slope are un-runnable. Sometimes it involves hands for scrambling and bouldering.

Mountain running takes more of everything than tamer trail running: more time, courage, adaptability, patience, calories, safety gear.

My initiation to true mountain running took place a decade ago, at the 2011 Hardrock 100, when I paced runner Garett Graubins over three mountain passes from Telluride to Silverton. Like an apprentice learning a craft, I studied how he efficiently hiked over the sharp, plate-like rocks of a talus field, and I copied how he bear-walked, using hands, up a wall of scree. When we got to a raging knee-high creek and a busted-up beaver dam blocked our way, I thought, “This can’t be right,” until I noticed a course marker in the middle of the logjam. I waded through the water and literally crawled over the pile of wood.

That’s mountain running: Be prepared to use your whole body, and expect the unexpected.

I met Christina near the Dexter Creek trailhead just north of Ouray’s downtown for a 17-mile loop with about 5,000 feet of vert. We jogged maybe a quarter mile up a ramp-like dirt road, then shifted to hiking up switchbacks so steep that our pace slowed to about 25 minutes per mile. In shadowy areas, where the temps stayed near freezing, our feet crunched over thick swaths of hail left over from the prior day’s storm. Golden aspen leaves dappled the trail.

I welcomed a “run”—a rugged hike—like this before my running shifts to more runnable, lower-elevation roads and pathways on hard-packed snow during winter. It feels so challenging, and satisfying, to lean into a steep grade and ascend the slope, planting trekking poles for added traction, and gaining elevation to the point where the trees wane at tree line.

Could I even call what we were doing a “run”? Yes, because as soon as the trail leveled out, we did indeed run. We moved as efficiently as we could, seamlessly shifting between hiking and running.

I’ve been thinking more about the concept of “mountain running” since I got to know a woman this summer, Whiley Hall, who is an exceptional, extreme mountain runner. Her specialty is peak bagging (i.e. summiting mountains), and at only 30, she is three-quarters through a mind-boggling goal of summiting every Colorado 13’er, which number over 700 (she already bagged all 58 14’ers). She won a 100-mile race, the High Five 100, that summits five 14’ers and requires self-navigation on an undefined, unmarked route. (Read my profile of Whiley here.)

When I learn about mountain runners at her level, part of me feels like a wimp. Mountain routes with exposure—meaning, they present a risk of falling because there’s a drop-off and nothing underfoot but the wobbly ledge you’re standing on—scare me.

Then I tell myself, that’s OK, even healthy. I don’t need to push myself so far out of my comfort zone that I’m in a danger zone. It’s satisfying enough to push my limits of endurance by mountain running on less-risky trails. Mountains offer different levels of challenge for all types of runners.

At the same time, Whiley and other mountain athletes inspire me by expanding my understanding of what’s possible with movement over these mountains.

“I just love being outside and moving my body through the mountains,” she told me. To that, I can relate.

***

Thank you for reading the third installment of my fledgling newsletter. For paid subscribers, I sent out a bonus post yesterday with recommendations for at-home conditioning, including a suggested workout, and an invitation to a Zoom that will be held Thursday, October 28, 5:30pm Mountain. The first meeting’s prompt will be, “What is standing in the way of better running or better wellness for you?” Please consider switching your subscription to paid if you would like to receive this bonus content and an invitation to the monthly online meeting.