Welcome back to Colorado Mountain Running & Living. This week’s installment is more of a “living” than “running” post. If you’d like to receive bonus content and join our monthly online meetup to talk about running & wellness, please consider subscribing at the supporter level. Our next Zoom will be Sunday, May 15, 4:30 p.m. Mountain.

Twenty-six days ago, I embarked on a “100 Day Creativity Project” with an online group. The idea is, you carve out a small portion of your day to be creative in any way that moves you. I tried to write descriptively, to close my eyes and call forth a memory and then transfer the scene and its senses to paragraphs.

A quarter of the way through, I’ve stalled. I began skipping days around Day 14. When I sat at my desk, I wanted to work—to complete tasks—not spend 20 or more minutes in reverie. When I managed to write something halfway creative, it felt forced and irrelevant.

It hit me that I am working, coping, and getting through each day. I am not dreaming, reflecting, or planning. I’m in this mode largely due to monitoring and responding to a controversy involving a fast-tracked high-density housing development near us. It has taken over my and my husband’s time and attention because many things we cherish about living here—the open views, the quiet dirt road, the long-term flow of water from the well that sustains us—all feel threatened now. My relationship to the town feels threatened, too, because many people disagree with me and want hundreds of homes to spring up on this rural, wind-swept mesa.

I realized how emotionally invested I am last Thursday when, during a seven-hour meeting via Zoom of our county Planning Commission, I gave four minutes of testimony (transcript here if you’re interested to read it), and two-thirds of the way through, my voice cracked and I felt tears sting my eyes. My Zoom video was turned off, so people attending the meeting could not see me, but they told me they could hear me start to cry. The Planning Commission narrowly approved on a 3 -2 vote the rezoning that will allow the development (news story here); now, the next step is a hearing in May before the three-person Board of County Commissioners, likely to approve it also. We still have opportunities to protest and negotiate. But I feel disillusioned by the decision-makers.

I have a sense of unease and unraveling. The term “unraveling” came up on this episode of “This American Life.” The things we used to take for granted—like, the school bus showing up to pick up your child, or the peaceful transfer of power between U.S. presidents—have been unraveling since the pandemic.

Several months ago, we hired a contractor on the recommendation of a real estate agent and paid this contractor tens of thousands of dollars to upgrade a family member’s fixer-upper. He lied about pulling permits, lied about the work timeline, and completely botched the job, so we had to fire him and start over, all that money and time lost. It’s a total mess and a story not worth telling here, but the point is, it shook my trust in people and dampened my optimism.

Seven years ago, when we invested all our resources and went deep into debt to buy this property and build a home on land that has held my heart since early childhood, we did it with the belief that this area would remain rural and undeveloped for future generations, thanks to legal contracts agreeing to rural and low-density zoning. This special slice of Colorado would remain unspoiled. Now, in less than two months, that belief has unraveled, those contracts have been ignored. What next?

In the face of this unraveling—the feeling of loss of control and doom, from the war in Ukraine to the change on the landscape—I focus on small joys, inspired by Ross Gay’s The Book of Delights (whose short essays I read at bedtime when I’m between novels, or when I’m too tired to read more than two pages), and this prompt on The Isolation Journals, “reasons to live through the apocalypse.” (How can one line be so depressing yet uplifting?)

These are a few of the small yet powerful and life-affirming joys I experienced in the past fews days:

I tore off the plastic covering a new salt mineral block for my horses and held it in my hands like a present as I stood before them. As their noses suspiciously sniffed the strange object, their sensitive lips, which are like our fingertips in terms of feel, rubbed against it. Together, two large tongues emerged, gliding over the hunk of salt. Heads together, eyes half closed in contentment, Maverick and Cobalt licked and slurped the salt block held aloft in my arms as if sharing an ice cream cone.

My adulting kids shared photos of them with their significant others from road trips last weekend, each capturing the sensation of a spring getaway, each signaling that they are healthy and enjoying life. Colly’s selfie showed her sitting next to her new boyfriend midway through a spring ski day, both smiling but half incognito from ski goggles. Meanwhile, Kyle shared a photo with his lovely long-term girlfriend, who has visited us and seems perfectly suited to him. They are sitting in a hot spring against a snowy background, and he is kissing her cheek. I feel infused with love and admiration as I read the swagger in his caption, “It was just the regular springs before we showed up.”

After three weeks of procrastination, I finally sat at my desk and focused enough to write a 1200-word article for a local magazine. I had put it off because I couldn’t focus, and so many weeks had passed since I did the interviews for it that I felt disconnected from the topic. Yet when I started organizing and writing it, it seemed so simple and pleasurable to shape and share this story. The procrastination seemed entirely unnecessary. I sent it to my editor, and she promptly replied, “Looks great on first read.”

I watched Morgan, sitting across from me at dinner as we ate a comfort dish made of beans and cheese topped with toasted breadcrumbs, as he assessed whether his gray hair has grown out long enough to pull into a full ponytail. He decided some time ago to stop bothering with haircuts, and he doesn’t want to shave his head as so many balding men do. He has been pulling the sides back into a small ponytail, so he allegedly looks more respectable on screen during Zoom meetings, although when he turns sideways, a perky small ponytail sticks straight out like a girl’s. Gliding his hands behind his head, pulling all his hair back, he realized that yes, it’ll all fit into a hairband now, which is good, because he may have to appear in court in California next week on behalf of a client. He may have to put on a dark suit and tie for the first time in about three years. Hands behind his head while pulling his hair tight, elbows pointing up to the ceiling, he lifted his eyebrows and made a crazed smile as I busted up laughing at the thought of him back in California court, thinking how great it’d be if he also could carry a chicken like a briefcase, the way his unprofessional Zoom profile pic shows him holding a chicken.

I heard the dogs, Dakota and Beso, yip with joy and as they leapt to the window seat cushion and rested their front paws on the windowsill to gaze outside, bodies quivering with anticipation. They spotted my brother’s beat-up Subaru coming down the driveway, his dogs—my dogs’ “cousins,” as we call them—sticking their heads out the car window, the sound of barking piercing the quiet. This is the highlight of my dogs’ day, when my older brother arrives to take the pack of four dogs on a walk by the river, and it is my joy, a reminder I have a brother across the road.

I walked out the door at daybreak to feed the horses, when the sky was transitioning from black to deep blue but it was still dark enough that the eastern ridges and peaks of the mountains formed a silhouette. A rustling to my right caught my attention, and I turned, not with fear but curiosity. I know it’s something from nature that makes the noise. And yes, the sound came from footsteps of an elk only 20 feet away, grazing next to the kitchen window. Dozens of her family and friends dotted the hillside. She and I saw eye to eye because we are about the same height, and we held each other’s gaze. I wanted to ask her why she grows thicker hair around her neck, like a scarf. Then she dropped her head to take another bite and ambled down the hill, turning away so I could see her blond backside. All the elk moved slowly, undisturbed by my presence. This is their home.

I could share many other moments of soothing joy and gratitude. Instead, I’ll end with a brief story that emerged on one of those days I sat to write for the creativity project.

I asked myself, why do I care so much about the land a half-mile up the road that is planned for development? Why do I feel a connection to it?

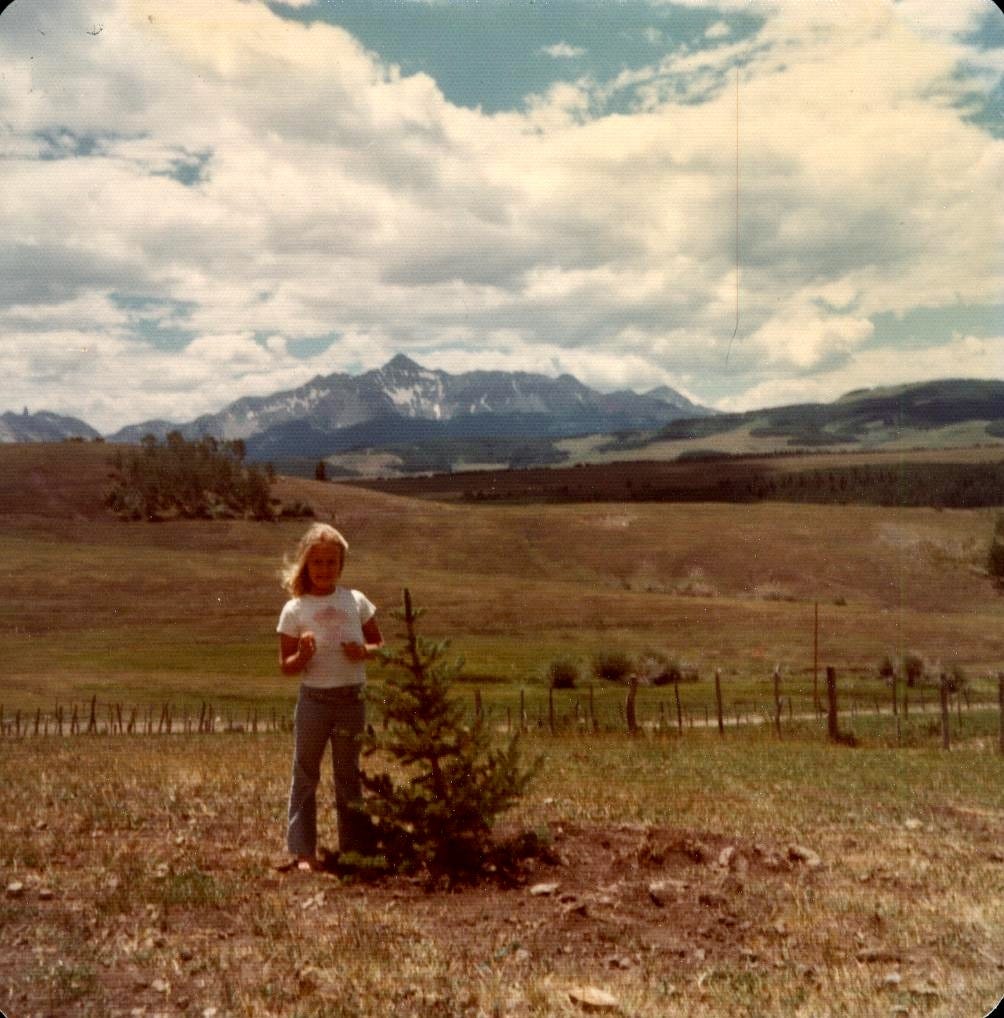

In my mind, I am 9 years old, summer of 1978.

My friend Michelle was spending the night in my dad’s cabin on Last Dollar Road. We lay on bunk beds in the corner bedroom in sleeping bags. Our family didn’t bother with bed linens in summertime; we slept on thin mattresses on metal bunks that must have come from an Army surplus store. Whenever I sat up on the bottom bunk, I had to be careful to avoid getting my hair caught in the coiled springs above.

Michelle and I hatched an idea. Let’s camp! Here, memory becomes faint, but this I know for sure: We packed a can of Pringles, two Welch’s grape sodas, a metal flashlight, and our Dell Yearling paperbacks (because we were book nerds). I draped my purple down sleeping bag around my shoulders and under my arms, not having a stuff sack. We opened the window to the bedroom, crawled through, and hopped out at night. My parents, at the other end of the cabin, had no idea.

We walked up the road—the dirt road I now drive, run, or ride the horses on daily. We were the only people out for miles, and this isolation must have made us feel safe. This was before the regional airport, before a couple of neighbors built homes on this bend of the road, so the only light that shown at night came from Dad’s cabin and the Aldasoro home a mile away on the other side of Deep Creek.

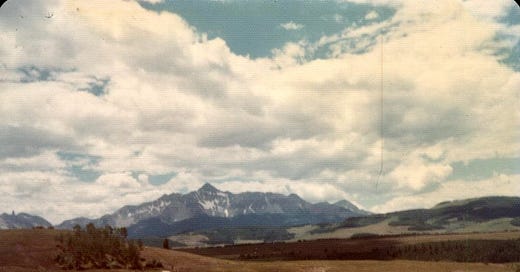

We headed to The Corral, the arena-sized wood-rail enclosure for sheep that used to exist at the side of the road where in a couple of years there may be roads with cul-de-sacs leading to hundreds of homes. The Corral, as everyone called it, encompassed a flat, grassy area with Wilson Peak to the south, Little Cone southwest, and an aspen grove on the hill to the east.

Michelle and I put our sleeping bags on the grassy dirt and slept there. I don’t remember other details about that night, but I recall the warmth of sunlight in the morning, and the absence of fear or guilt as we confidently walked carrying our stuff back down to the cabin. I did not worry about my parents’ reaction, because they wouldn’t know—or if they did know, wouldn’t care—that we had chosen to sleep outside. I felt some pride, because we had done something that my older sisters and brothers might do. I felt both safe and wild.

That opportunity to sleep on this high-top pasture encircled by mountains, under the stars—to walk safely up a dirt road at night, no one else in sight—is something I wish I could pass on to my future grandchildren, but now, like The Corral, it’s one of the things that used to be.

Related posts:

Sarah, I always enjoy your writing even though I am not a runner. I feel blessed to have spent a summer in Telluride in the 70's before so many changes. When the campers were off on trips we were able to see a lot of the territory. I was able to read your grandfather's autobiography with an improved awareness of

the area. I appreciate your efforts to save the area from excessive development, your family of the past would be proud once they got over the shock. My best wishes in your efforts to maintain the quality of mountain life.

Absolutely heartbreaking. I’m so sorry you are dealing with this tough situation.