Nostalgia typically triggers the feeling of longing or loss, but not always. Sometimes nostalgia hits with pleasant rather than painful sentimentality and the realization, that was then, this is now, and I value both. Or even, I’m better now.

I felt that way as I contemplated the past on my long run Saturday, when I felt nostalgic for several reasons—it was my son’s 24th birthday, I’m heading back to my high school for my husband’s 40th reunion (where we met as students), and 10 years have passed since I first found myself on the snowy alpine basin I was traversing—but oddly, I didn’t want to rewind time. I didn’t want to go back. I actually feel better in many ways now in my mid-50s compared to mid-40s.

I transitioned from running a relatively flat mining road to hiking up a talus field—meaning, a mountainside made of chunky rock—right around timberline, 11,500 feet elevation. No one was near me, only scampering marmots and flowing water caught my eyes and filled my ears. I wanted to go higher, but snow fields blocked the way, and I got tired of feeling my shins scrape against sharp snow as my feet post-holed, so I took a moment to rest and look around before descending.

I felt unhurried and settled—a peaceful feeling that, I believe, comes more with aging.

Looking south, down Marshall Basin toward Telluride, I marveled at the enormity of the snow-streaked mountains and all the history they’ve witnessed, as the slopes below me once were home first to Utes, then to those who worked at the Tomboy and Marshall mines that became thriving settlements in the late 1800s. I tried to picture my grandfather’s stepfather, Ed Lavender (who married my great-grandmother after her divorce, adopted my grandpa, and gave us all the Lavender name), leading a mule train or driving a horse-drawn wagon up these slopes, since in the early 1900s he provided supplies and transportation from town to these mines.

Then I turned around and looked northward, craning my neck up, to see Virginius Pass at 13,000 feet. The notch in the rock is where runners cross over from Ouray during the Hardrock Hundred (circled in this photo). If all goes well, I’ll cross over there, which is mile 70 on the 102-mile route, at daybreak on July 12, about 24 hours into my “run” (which will be more of a long hike).

Virginius Pass is also likely where the first white prospector, John Fallon, crossed over in the summer of 1875, right after an agreement with the Utes opened these mountains to prospecting and settlement. With mules carrying supplies, he hung out right where I was hanging out, used his feet to measure and mark claims (each 1500 feet long and 300 feet wide, or close to 10 acres), and dug around to get samples of ore. When he made it back to Silverton and got paid some $10,000 for the gold in the ore, he sparked the mining boom above Telluride that started in the spring of 1876. One to two decades later, immense construction and drilling were underway in Marshall Basin and neighboring Savage and Liberty Bell basins, and the wooden husks and metal junk of all their mining and housing infrastructure remain on these mountainsides.

In short, I was pausing and thinking in a spot that was conducive to considering history’s passage of time and change through generations, and to feel the presence of ghosts who reminded me of my limited time here.

I thought about my first time on Virginius Pass, summer of 2015, when I paced my friend Clare, who was in Hardrock, from Ouray to Telluride (first photo below). I feigned confidence but felt utter intimidation as we faced a snowy, icy headwall on the slow-to-melt north side (coming from Ouray), and then we had to descend the crazy-steep south side, the slope made of slippery shards of rock called scree. The following summer, I hiked up to Virginius for the first time from Telluride with others training for Hardrock (second photo).

In my mind, I did a quick comparison of my 2015 self to today and reflected on how much my life had changed in a decade. I had no idea then that I’d end up here, with these mountains as my full-time home, or that I’d finally be getting my chance to do the Hardrock Hundred.

The summer of 2015 set my life on a different course. It’s not just that I got hooked on Hardrock and gained the gumption to enter my first qualifying race that year, the Wasatch 100, and started a decade-long process of entering Hardrock’s lottery to gain an entry spot this summer. It’s that we made a snap decision late that summer to buy property outside of town, on acreage across the road from my dad’s old cabin where my brother now lives.

I’ll share some decade-old flashbacks not only to reveal more about who I am, but to show how you might want to trust your gut telling you to go in a certain direction, and take chances for the things about which you care most.

In 2015, when I was turning 46, I was peaking as an ultrarunner, coach, and for a short-lived time as an “influencer” (a new term then) in the sport, since I wrote regularly for Trail Runner and co-hosted one of the first ultrarunning podcasts. I cared 10 times more then about my place, performance, and reputation than I do now.

My husband and I celebrated our 25th anniversary in New Zealand, where I raced the 2015 Tarawera 100K and set a PR for the distance in 11:57. My most vivid memory from that race involves a rotten banana. I was racing so hard to finish under 12 hours and to catch the women ahead of me—and I was bonking so hard—that when I spied a blackened banana on the roadside in the final miles, likely tossed from a car, I didn’t hesitate to grab, peel, and inhale it. I raced as if possessed, and that banana saved my race. I was much more competitive then, approaching every race as a race, not just a run.

Outside of running, I was preoccupied with my kids. My daughter was about to start the college application process. My son was about to leave home and start ninth grade at the boarding school in Ojai, called Thacher, where our daughter went and where my husband and I went (our family has a long history with that school, and I grew up there as a faculty kid since my dad worked there, so it’s like a second home).

I worried about my son being homesick and struggling academically. I worried about my daughter’s anxiety about getting into a top-choice college. I worried about myself as a full-fledged empty-nester, because my role as mother defined my life more than anything. I worried about turning 50, which seemed so old, and slowing down and becoming weak and infirm like my widowed mother.

I worried so much!

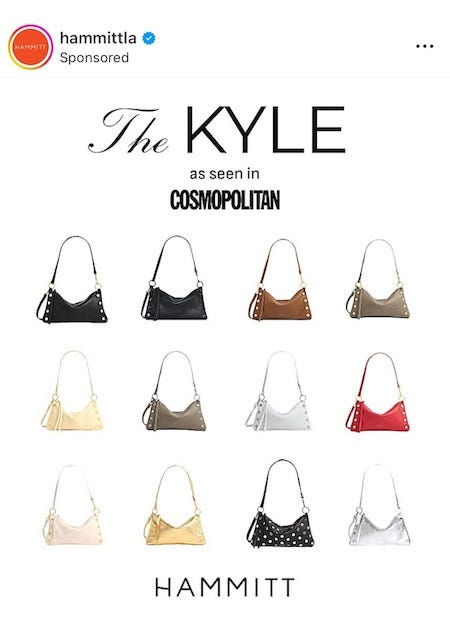

If only I could’ve looked 10 years into the future then. I’d see my daughter, a graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, making bestselling designer handbags (one of which she named after her brother, see an ad from Instagram below), then leaving that company recently to launch her own company. I’d see my son graduating from CU Boulder and following his desire to work with horses. They both got through adolescence, figured out what they wanted to do, and turned into adults who fill me with admiration and love.

In 2015, my husband and I were still living and raising our family in the East Bay Area neighborhood of Piedmont, a sought-after small town between Berkeley and Oakland. Socially, I always felt like a square peg in a round hole there. Our four-bedroom, century-old house always felt too big and formal for my tastes. I fantasized about a farmhouse with horses in my life again. I felt drawn to Deep Creek Mesa outside of Telluride, where I had spent so much of my upbringing (Dad built a summer cabin there in 1973; his dad was born and raised near there).

We spent much of the summer of 2015 living in that cabin with my brother and sister-in-law, partly to house-hunt and consider buying a second home in Telluride that we could rent out and visit regularly. But we were so turned off by the high prices and summertime crowding in town, we gave up on that idea.

Then a neighbor stopped by the cabin one afternoon and over a beer gestured to the property across the road, which had been my extended playground when I was a kid. It was the acreage where the sheep-raising family, who owned most of the surrounding land, often kept their herd of horses, and my sister and I used to catch and ride those horses. It was the paradise of my youth.

“You know, the best parcel on the market is that one,” he said, and he explained it was for sale and would likely go quickly because the parcel next to it had just sold to the Henson family of Muppet fame.

In an instant—a kind of Blink moment—Morgan and I felt certain that we must do everything possible, and leverage all our finances and go into deep debt, to get that land. We didn’t know if we wanted to move there year-round or even what kind of home we’d make there, or how he’d continue to lead his Bay Area firm; we just knew we needed it in our family, not only for us, but to prevent some stereotypical rich person from Hollywood or Texas from building a mega-mansion across from the beloved family cabin that now belonged to my brother. I also wanted live near my brother to help him care for our declining mother.

So we stretched and made it happen. We put all our metaphorical eggs in the basket of 35 sublime acres. We gradually transitioned from California to Colorado, living in a trailer and putting the kids in a tent while we figured out what to build, how to afford it, and how to handle and shift our careers. The kids convinced us to buy a horse the following summer, so we built a barn with a horse paddock before we built a house for ourselves.

It all worked out.

Yesterday, as I sat in a hair salon and watched the woman who specializes in Botox, fillers, and weight-loss drugs take in clients—her face literally burned and peeling from a laser treatment, her lips ballooned from injections and cheekbones jutting out from implants—I reflected on how we’re sold on the idea that younger is better and aging should be defied. More and more, I’m rejecting that notion (letting my face age naturally, but hypocritically still coloring my hair to blend in the gray—maybe I’ll let that go, too), because I’m content how I am and grateful my younger self worked hard and evolved to land here.

I’m going to soak up each week, month, year, and try to pause more frequently as I did on my run to appreciate it and reflect on the past, but resist yearning for the way things were or the way I was.

I’ve slowed down as a runner and more generally in life. Life still gets complicated, bad news chronically looms, anxiety simmers about my kids’ future. These mountainside moments don’t indicate that I’m always living easy in an idyll. But I’ve reached a place of gratitude and perspective—and acceptance of aging (it’s better than the alternative!)—that helps me pause and appreciate the present, and to be more curious than frightened about what surprises the future might bring.

When my rest break was over, I ran down the mountainside trying my best to be nimble on the rocks and emulate the flow of the snowmelt’s runoff, reflecting on the ambiguity and time-shifting of Dylan’s line, “I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

I always look forward to your weekly reflections, and this one didn't disappoint! As I struggle with getting older and slower, your words reminded me what a privilege it is to still be moving in the way I want to move, in places that are beautiful. Did you know that the July full moon is on July 10? That means on July 12, as you descend from Virginius towards Telluride, you'll have a spectacular moon setting in the (hopefully clear) pink sky of sunrise. And that we will have it light our path up and down Putnam the next night! Cheers to simple gifts! XO

Thank you for this reminder and your reflections Sarah! What a gift to read this today. Thank you. I really needed this.